|

| Paula Cartern / Harvard College Library |

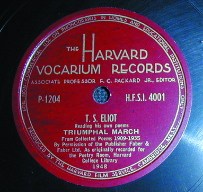

Launched in 1931 (in collaboration with Harvard's Poetry Room, the Harvard Film Service, and the English Department) by Frederick C. Packard Jr. '20, a Harvard professor of public speaking much interested in recording voices, the Harvard Vocarium label persisted through the early 1950s. Dozens of poets and other writers read their works, among them Tennessee Williams, W.H. Auden, Robinson Jeffers, Marianne Moore, Archibald MacLeish, Theodore Roethke, Muriel Rukeyser, and Robert Lowell. Meant to foster the "appreciation of literature," the phonograph records were sold to the public and have been in continuous use at Harvard by students and researchers. About 110 records were made, according to Donald Share, present curator of the Woodberry Poetry Room in Lamont Library.

The entire corpus has been chosen by the Library of Congress for inclusion in the first annual selection of recordings for the National Recording Registry. "Congress created the registry to celebrate the richness and variety of our audio legacy," says Librarian of Congress James H. Billington. The inaugural set of 50 recordings emphasizes, he says, "important firsts in the history of recording in America: technical, musical, and cultural achievements."

The Vocarium series shares registry honors with such landmark items as 1890 field recordings of Passamaquoddy Indians, Caruso singing "Vesti la giubba" from Pagliacci in 1907, vaudevillian DeWolf Hopper reciting "Casey at the Bat" in 1915, Bessie Smith singing "Down-Hearted Blues" in 1923, and the first radio-broadcast version, in 1938, of Abbott and Costello's "Who's on First." Elvis is on there, of course. (For the entire list, go to www.loc.gov/rr/record/nrpb/nrpb-nrr.html.)

"The actual artifacts the cylinders, discs, piano rolls are at the heart of the registry," says Share. "Preserving, restoring, and digitizing them, and then storing the results in a permanently safe place, ensures the future survival of these priceless and unique recordings." The Library of Congress won't re-release any of the recordings in the registry commercially, but the recordings will be available to the American people on site and perhaps to some extent on-line if copyrights permit.

The poetry room has almost 60 years of similar recordings not on the Vocarium label. A core part of that collection is to be restored and digitized, thanks to Rob Hildreth '72. "The result will be on-line access to our recordings, which are now accessed only on site," Share says. "So, we've got two wonderful projects underway to restore and reformat our unparalleled audio collections."