Every day in Dallas, people gather in Dealey Plaza to look up at the sixth floor of what once was the Texas School Book Depository. Some lay flowers to commemorate a moment that changed America and history. For Michael H. Collins '71, J.D. '77, general counsel of the Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza in Dallas, these impromptu gatherings prove the importance of the institution that he has served for more than a decade and that his father, William E. Collins, J.D. '48, helped found amid much opposition.

|

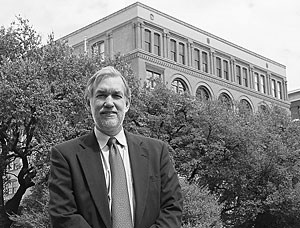

| Michael Collins at the Texas School Book Depository |

| The Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza |

"People were coming of their own volition to this site on a regular basisto look at it, to be there on November 22," Collins says. "[People felt]...a need to be there and to know and understand and make sense of it." That is the role of the Sixth Floor Museum, he says. Opened on Presidents' Day 1989 and drawing more than 400,000 visitors a year, the museum offers a permanent exhibit examining John F. Kennedy's life, legacy, and death that includes documentary footage, artifacts, photographs, and the precise location from which, authorities have concluded, Lee Harvey Oswald gunned down the president. The museum also details the many conspiracy theories surrounding the assassination.

William Collins, who died in 1997, was among the small number of Dallas residents who worked to establish a museum in the building that now serves as the seat of county government. In a memoir, he called the result of that work "perhaps the most rewarding of anything I've ever done." His son says that's because many residents wanted the building torn down, erased from the landscape, as if a day that tarnished Dallas, for some, as a "city of hate" could be erased as well. It was a sign of the city's maturity, Collins adds, that his father and the other advocates secured local funding to make the museum a reality. "The idea from the beginning was not to make this some sort of glamorization of the Kennedy era or make it a defense of Dallas or to take a position on the assassination but to [have] a sober, reflective place where the story got told and people could draw their own conclusions as to what happened," he explains.

The museum struggled at the start, according to Collins. Then the release of Oliver Stone's film JFK in 1991 renewed interest in the assassination and increased the number of museumgoers. Since then, the nonprofit organization has been financially sound. In the early 1990s, Collins succeeded his father as a member of the museum board; in 1998 he became general counsel. As the museum's attorney, working pro bono, the partner at Locke Liddell & Sapp oversees intellectual-property, real-estate, and licensing matters, including licensing the Zapruder film of the assassination, of which the museum now owns the copyright.

Interest in the assassination and the Kennedy mystique remains strong, Collins says, though younger visitors lack the personal connection of those who were alive at the time. As the fortieth anniversary of the assassination approaches, he recalls the crowds that swarmed the area and the museum in 1993; he calls that anniversary the "defining moment [that put] the seal of approval on the institution." This year, the museum is co-producing a historical documentary on local news coverage of the assassination, mounting a new photography exhibit, hosting a daylong symposium reexamining Kennedy's life and legacy for its oral history collection, and presenting the Dallas Symphony Orchestra premiere of Leonard Bernstein's Mass. And Collins knows the crowds will gather again.

~Lewis Rice