Several Harvard professional schools and one institute have begun layoffs this summer in response to the federal government’s actions: a federal funding freeze, the potential loss of international students, and an increased tax on endowment investment gains from 1.4 to 8 percent, embedded in a spending bill U.S. President Donald Trump signed on July 4.

The layoffs come atop a University-wide hiring and nonunion salary freeze instituted earlier this spring. More job reductions are expected, even as the University and the federal government attempt to negotiate a settlement.

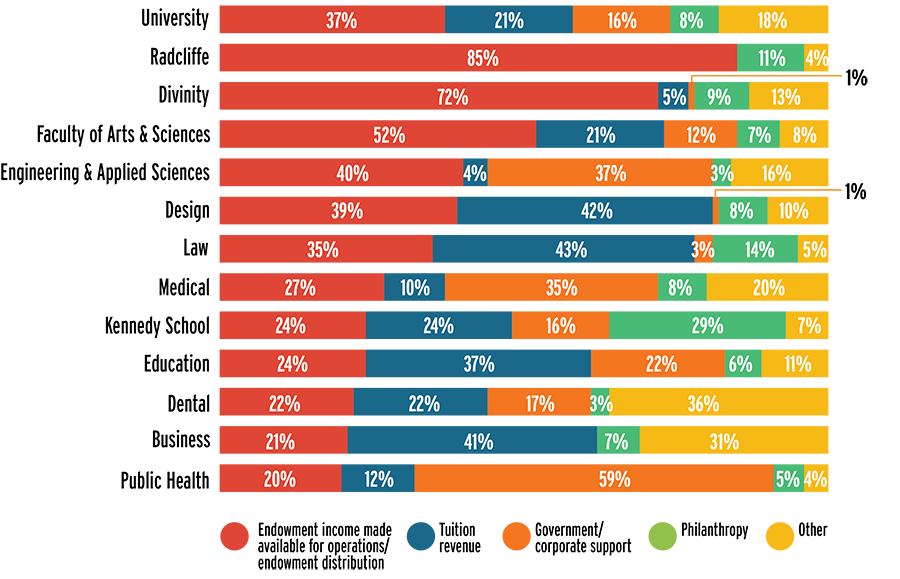

Fiscal Year 2024 Sources of Operating Revenue by School

The extent of the layoffs varies by each school’s exposure to the three sources of operating revenue implicated in the government’s actions: federally sponsored research; endowment funding for operations; and tuition income from international student enrollment. The school most affected is the T. H. Chan School of Public Health, where federally sponsored research was 46 percent of operating revenue in fiscal year 2024 (July 1, 2023 - June 30, 2024), and international students represent 42 percent of the student body. The Chan School began layoffs in April and says more are coming on a rolling basis, though a spokesperson declined to provide specific numbers.

In late June, the Harvard Kennedy School of Government (HKS) laid off an undisclosed number of administrative and support personnel and announced that if international students were unable to return to campus in Cambridge for their second year, and a significant number expressed interest in in-person instruction, they may be offered the option of completing their degree at the University of Toronto’s Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy. Last year, 56 percent of the HKS student body was international. Nearly a quarter of the school’s income is tuition revenue. As at other schools, construction projects are being wound down, and leased space is being relinquished as the school minimizes its physical footprint.

At Harvard Medical School, which relied on sponsored research for more than a third of its operating revenue in fiscal year 2024, layoffs have not been formally announced. But in April, department and unit leaders were asked to reduce their budgets by 15 percent for the fiscal year that began on July 1, which may affect both programs and personnel. Tuition and endowment each provide a little less than a quarter of the school’s revenue, and international students make up 24 percent of the student body.

Next door, at the Harvard School of Dental Medicine (HSDM), there will also be layoffs. The school is protected by the fact that 36 percent of its annual revenue comes from clinical revenue: it is the only Harvard graduate school that provides direct patient care, through Harvard Dental Center clinical practices in Longwood and Cambridge. Still, the dental school has lost $9 million annually in federal funding for basic, translational, and clinical research—in areas including infectious disease, functional genomics, craniofacial and bone biology, stem cell biology and regenerative medicine, molecular and mucosal immunology, bioinformatics, and population health.

Tuition payments and endowment income each provide 22 percent of the dental school’s annual revenue. A quarter of the student body was international in the fiscal year 2024.

At the nearby Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering, the impact of federal grant cancellations remains unclear. For example, institute director Donald Ingber explained earlier this week, “We have some grants where we have not received any notice of cancellation or stop work orders, but the invoices are not being paid. We are currently trying to manage the situation through natural attrition (sometimes to start-ups), as well as enforcing a freeze on salaries and hiring.”

Ingber noted that further actions may become necessary, depending on the outcome of Harvard’s lawsuit challenging the federal funding freeze. For the time being, he said, “we are still stuck in the damage assessment mode.”

In East Cambridge, at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, the biomedical research center that played a key role in tracking the evolution of COVID-19 variants during the pandemic, 75 mostly administrative employees were laid off in late June. The institute is also curtailing certain employee benefits, suspending raises for more highly compensated employees, and reducing spending on events.

At the University’s schools of law, divinity, and business, and at the Radcliffe Institute, federally sponsored research ranges from miniscule to nonexistent. But at Radcliffe and at the divinity school, which are dependent on endowment for 85 percent and 72 percent of their annual operating revenue, respectively, the 8 percent tax on endowment investment gains will have at least some financial repercussions.

At both the business and law schools, by contrast, tuition income contributes more than 40 percent of annual revenues. While both enroll international students, just 17 percent of law students were international in fiscal year 2024, suggesting a minimal impact, even if litigation surrounding international enrollments remains unresolved.

The business school, where 37 percent of students were international that year, is more exposed to the risk that foreign students might be denied visas (although it also possesses advanced online education capabilities and runs eight international research centers). A school spokesperson declined to comment on the possibility of layoffs for this article.

Three positions have been eliminated at the Graduate School of Design due to increasing financial pressures, including uncertainty around international enrollment—56 percent of the student body was from abroad in fiscal year 2024. Of the positions eliminated, one was vacant at the time. Another employee was reassigned to a different role within the school, and a third was laid off.

Within the Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS), which includes Harvard College and the Griffin Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, the strategic plan for managing funding cuts was announced by Dean Hopi Hoekstra at the May 5 faculty meeting. A task force has been considering staff reorganizations, and some layoffs have reportedly already begun. Nonessential capital projects and spending have been suspended. Central University funding is being used to sustain ongoing research projects while litigation over federal funding continues.

The Graduate School of Education, which did not provide information about its plans prior to the publication of this article, is also vulnerable to funding reductions. For its annual revenue, the school relies on endowment income for 24 percent, on sponsored research for 22 percent, and on tuition for 37 percent. With an international enrollment of 38 percent last year, all three of those revenue sources—which represent in total 83 percent of the school’s annual revenue—are at some risk. Spending cuts are likely.

Finally, at the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, where sponsored research projects provided 37 percent of operating revenue in fiscal year 2024, the impact is likely to be severe. The school, which did not provide information about its plans prior to the publication of this article, does benefit from a substantial endowment that provided 40 percent of its operating revenue in the last fiscal year, but its exposure to sponsored research is triple that of FAS and comparable to the medical school. The school also operates a relatively new building in Allston, the Science and Engineering Complex, which reportedly cost more than $1 billion.

The varied impacts across schools highlight the risks of Harvard’s financial operating model, traditionally described as “every tub on its own bottom.” And they underscore the risks of global engagement at a time of rising nationalist actions by the federal government.