With its booming factories, roaring steam engines, and great, groaning machines, the Industrial Revolution made quite a racket. Surrounded by such unprecedented noise, it didn't take long for Victorian writers such as Charles Dickens and George Eliot to consider the possibilities of sound and silence as powerful literary symbols for characters' psychological insights and sympathetic relationships.

|

| Punch, 1845 |

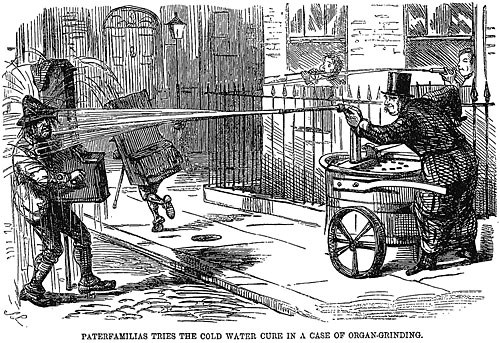

"Up until then, nobody really bothered to pay attention to noise. It was just something in the background," explains assistant professor of English and American literature and language John M. Picker. His recent book, Victorian Soundscapes, examines how the era's scientific and technological innovations changed perceptions and interpretations of sound and listening, particularly in literature. "On a larger scale than before, noise began in this period to alter the agents, subjects, and conditions of artistic and intellectual occupations," he writes. London's myriad cacophoniesfrom organ grinders' relentless whines to locomotives' piercing shriekswere inescapable and often vexing, permeating homes, offices, and sanities.

This was an age, Picker continues, "defined by new emphases on and understandings of the capacity for listening." New technologiesincluding the telephone and phonograph, which appeared in the late 1870senabled Victorians to hear not only their own amplified voices (phonographs even let people record themselves in their own parlors), but also what had been almost inaudible, such as the murmurs of their hearts and lungs. The era's scientific and artistic developments marked a shift away from the pastoral experience celebrated by Romantic writers such as Wordsworth and Coleridge, and granted sound and listening exalted literary roles previously reserved for those stalwarts of perception: sight and gaze.

As the sun set on Wordsworth's arcadia, it rose on Dickens's vibrant London. "Clanging bells, cracking whips, clattering carriages" is how Picker describes the din. He relates the extraordinary brouhaha over the city's street musicians, whose unceasing and jarring performances provoked vitriolic editorials and restrictive legislation. Dickens himself weighed in, deriding the buskers as "bangers of banjos, clashers of cymbals...bellowers of ballads."

|

| Punch Almanack, 1858 |

Picker focuses on Dombey and Son (widely considered the novelist's breakthrough work) and its exploration of sound and perception. Although the novel "roars with the tumult of rail and sea," he writes, it also examines the "problems and impossibilities of hearing as well as of understanding voices." He provides numerous examples of misunderstandings, of characters having to repeat themselves, and of other breakdowns in communication. In one example, young Paul Dombey asks insistently, "The sea, Floy, what is it that it keeps on saying?" But as Picker points out, "the waves never precisely disclose or clarify themselves: they never say what they mean."

Dickens was particularly enchanted by the notion of sound waves' permanence and the implied promise of immortalitya theory expressed by his friend Charles Babbage, the inventor and mathematician. "The air itself is one vast library," Babbage wrote, "on whose pages are forever written all that man has ever said." Dickens not only referred to this theory in Dombey and Son, but tested it in pursuit of what Picker calls "the fantasy of literary immortality": he suggests that the famous novelist's ambitious reading tours through England and the United States may have been partly inspired by Babbage's idea.

While Dickens's voice boomed across lecture halls, George Eliot was exploring the burgeoning science of acoustics. Her notebooks reveal her interest in Hermann von Helmholtz's groundbreaking theories, particularly the phenomenon of "sympathetic vibration": when the vibration of one sonorous body (such as a ringing bell) produces a sound of the same pitch in a neighboring sonorous body. "Thus the pitch of the notes of a church bell may be ascertained by playing upon a flute under the bell," Eliot wrote; later she used the same image in Middlemarch.

|

| Detail of cartoon, Punch, 1886 |

Sympathetic vibration resonated with Eliot's longstanding interest in sympathy as a literary theme, and she readily transformed the scientific phenomenon into a literary metaphor for mutual understanding and emotional connections. In "Mr. Gilfil's Love-Story" from Scenes of Clerical Life, Eliot describes a character's emotional response to a harpsichord's note: "the vibration rushed through Caterina like an electric shock: it seemed as if at that instant a new soul were entering into her, and filling her with a deeper, more significant life."

But for Eliot, silence was as meaningful as sound. "Her books are filled with silences, which are typically moments of repression for her characters," Picker explains. These repressed characters are often women, such as Daniel Deronda's Gwendolen who, Picker contends, "can listen, but is not allowed to speak out." Eliot was "uniquely sensitive to the muffled women's voices that often tried to speak behind the silent curtain of the Victorian institutions of femininity, domesticity, and marriage," Picker writes. For such characters, solace is often found in a sympathetic person whom Picker calls "a close listener." For Gwendolen, Daniel is the listener to whom she can finally speak freely; he becomes, in Picker's words, "the resonant repository for...[her] confessions of guilt and selfishness."

Picker credits Eliot with an ability to appreciate what he calls "the intimacy that exists within a closed circle of speech" and notes that Freud, who would later embrace sympathetic resonance as integral to psychoanalysis, was amazed by Daniel Deronda. "What makes Gwendolen's scenes with Daniel stand out as much as they have in criticism of the novel," Picker writes, "is that they capture this process of listening to the body with a precision few fictions before it had attempted."

~Catherine Dupree

John M. Picker e-mail address: picker@fas.harvard.edu