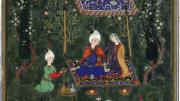

Take heart. Fancy that you sit on this carpet holding hands with your lover in a Persian spring garden. Your servant offers wine in a golden bowl. Musicians and dancers amuse you. Take heed of the inscription above the canopy, patterned with its exuberant arabesque. The lines by the fourteenth-century Persian poet Hafiz were translated by the historian of the Safavid dynasty Martin Bernard Dickson as “A rose without the glow of a lover bears no joy;/ Without wine to drink the spring brings no joy.”

Lovers’ Picnic, Painting from a Manuscript of the Divan [Collected Works] of Hafiz is an unsigned miniature, measuring 7.5 by 4.9 inches, attributed to Sultan Muhammad by the late Stuart Cary Welch Jr. ’50, G ’54, and dated about 1526-27. It is in ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper. Welch gave the painting to the Arthur M. Sackler Museum, a part of the Harvard Art Museum, in 2007.

Sultan Muhammad was “a powerfully inventive and expressive artist,” to the eye of Mary McWilliams, the museum’s Calderwood curator of Islamic and later Indian art. Lovers’ Picnic, said Welch, is “probably the most romantic picture in all Persian art, with one of the liveliest arabesques: dazzling, deeply moving, and wonderful.”

The painting rejoins other parts of the Divan manuscript that Welch gave Harvard earlier, most notably its exquisite lacquer book covers, text block, illuminated frontispiece, and two other paintings. Thanks to Welch, Harvard shares another of the manuscript’s four surviving paintings, Sultan Muhammad’s Worldly and Other-Worldly Drunkenness, with the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Cary Welch died of a heart attack last August at 80 after running to catch a train in Hakodate, Japan. He was curator emeritus of Islamic and later Indian art at the Harvard museum, which he transformed through gifts of almost 400 works of art. He had previously been special consultant in charge of the Islamic art department at the Met. He had immense artistic discernment and virtually invented the field of the study of Safavid painting and drawing. He bought his first Indian drawing at the age of 11. When he came to Harvard College, he was dismayed to discover no courses in Indian or Islamic art, so he taught himself: by reading, by traveling, and by seeing well. He wrote books, lectured to students, and distributed enthusiasm, but he was no academic. He once wrote to a fellow connoisseur, “I know, from experience, that you are too alive for the academic world....Don’t sign yourself up for dreary years of academia. Leave that stuff to the eunuchs.”