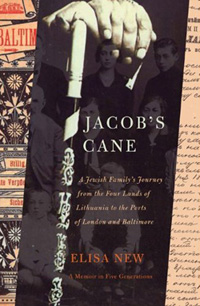

A meticulous excavation of personal history, Jacob’s Cane: A Jewish Family’s Journey from the Four Lands of Lithuania to the Ports of London and Baltimore (Basic Books, $27.95), took professor of English Elisa New to the Baltics three times to construct “a memoir in five generations.” From her researches, she emerged with details evocative, emotionally resonant, and funny—as in this excerpt from chapter nine, “The Social-eest.”

What had possessed my great-grandfather in 1914 to commit his time and energy to a run for Congress he surely knew would be unsuccessful? Like the questions surrounding Jacob’s birthplace, Amelia’s illness, Uncle Baron’s character, and Jean’s decision to send her sons to England, my aunts didn’t agree on an answer. Why should their father have chosen so quixotic a way to spend the spring, summer, and fall as the Socialist Party candidate to represent Baltimore in the Congress of the United States? And why, after this venture failed, did he continue to defend socialist ideas in spite of his business success and his family’s bourgeois aspirations?

Aunt Myrtle and Aunt Jean each had her own way of explaining what it meant that their father—a captain of industry, as they represented him—could be a Red and a foe of unions simultaneously.

From a certain slight tightness around the mouth and the faintest wrinkling of her nose, Aunt Myrtle showed that to her socialism mostly meant domestic inconvenience. As the person who took care of her father in his later years after his wife was institutionalized and after Jean had moved on to her second of three husbands, living with him and keeping him in breakfasts and dinners, in clean shirts and pocket squares, in stamps and envelopes and typewriter ribbons, Myrtle had the experience to prove that political commitments are hell on the housekeeping. With the whole top floor of her house given over to her father’s comforts, every entrance through his bedroom door was a rich tutorial in the slovenliness of the intellectual.

Cheap weeklies dropped by the armchair, books piled in teetering heaps, ashtrays overflowing, cigarettes loose, coffee dried to syrup or Scotch whisky left in a cup—such were the habits of international socialism.

For Aunt Myrtle, her father’s socialism made him late to dinner, distracted with his children, tedious in company, and intolerant of what others thought “nice.” She, who could set her boys’ rooms to rights in fifteen minutes, came to know well the graceless habits of a sardonic socialist. Or at least she knew the tastes of one without a wife to keep him in line. His daughters did their best to cope.