On March 19, several Harvard schools had meetings with their local alumni. In addition, the Harvard Alumni Association convened a meeting of Asian alumni clubs, and Harvard China Fund hosted a luncheon for faculty members, friends, and others who had provided support for students from through the University during their research, internships, or studies in China.

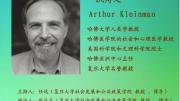

In two separate events, Harvard connections to China were made manifest in Shanghai itself. During the morning, Fudan University hosted a lecture by Rabb professor of anthropology and professor of medical anthropology Arthur Kleinman, part of a series called the Contemporary Anthropology Forum that drew both anthropology graduate students and medical students, reflecting his dual disciplines and the topic of his address. And in the afternoon, the Graduate School of Design hosted a trip to the Shanghai Expo 2010 site—where alumnus and visiting faculty member Yu Kongjian has created an ecological waterfront park—and to the city’s urban planning exhibition hall. Highlights follow.

Ethnographic Perspectives on Caregiving

Kleinman’s connection to Fudan is not incidental. Among other ties, his student Pan Tianshu, Ph.D. ’02 (read about Pan’s research here, and his review of a book on China’s migrant industrial workers here), is now an associate professor at Fudan’s School of Social Development and Public Policy. He invited Kleinman to talk about his current work, combining his scholarship in anthropology and social medicine with his recent personal experience of providing care for his wife, who has been disabled by Alzheimer’s disease. Kleinman, like many other faculty members, has advised, hosted as fellows at Harvard, and worked with dozens of Chinese colleagues (read about some of Kleinman’s work); in the aggregate, large and deep networks of academic collaboration have been created in virtually all fields and professions. Kleinman’s talk at Fudan, before an overflow crowd of interested, responsive students, was emblematic in a small way of University relationships nurtured for many years.

Caring for children, the elderly, the disabled, or those harmed by catastrophe, Kleinman said, is both an individual transaction and, in ethnographic terms, a reciprocal, biosocial activity of crucial importance both to the giver of care and to the recipient. It is part of what he called the “popular” sector of healthcare: neither professional medicine nor folk remedies, it is individual- and family-based. In fact, such popular care accounts for a majority of health care, he said; formal biomedical care—the application of drugs, medical procedures, and technology and devices—has ever less to do with this kind of caregiving, particularly as it comes under the constraints of more restrictive payment mechanisms. Up until a century ago, before biomedical research delivered modern drugs, medicine was principally caregiving, Kleinman observed, much of it delivered domestically, not in the hospital or clinical setting. Today, in societies like the United States, such caregiving by medical professionals is a rarity.

As a result, caregiving is little studied or understood. Its core tasks, as he had learned through caring for his wife, consisted of practical assistance to perform the tasks of daily living; acknowledgement and affirmation of the other person; emotional support; and expressing moral solidarity with and responsibility for the other. The latter three, obviously, are emotional and moral tasks. At life’s end, they are complemented by consulting and coordinating with the financial, religious, and other advisers of the person being cared for; and presence—being there with and for the dying person, when any expectation of recovery and continued life has passed. Seen in this light, caregiving is an existential act that defines our humanity and our relationship with other people: one of the activities that really matter in life. It is not at all a “burden,” in the economic sense; rather, it is a fundamental “way of being in the world” as a moral, ethical human. In a materialistic, cynical era, Kleinman said—perhaps with special resonance for his audience—caregiving is thus “one of the truly worthy objects of commitment.”

Anthropologists, he said, had studied the formal, professional aspects of medicine and healthcare, but had overlooked these elements of personal caregiving. Its importance stood in inverse relation to its social and professional status: family care ranked far below that accorded to care delivered by, say, a doctor—and in fact was largely relegated to women, who traditionally have held lower status within families, professions, and society.

He urged that moral life, the values underlying life, as expressed in acts of caregiving, be subjected to the study, understanding, and appreciation that they deserved.

Photograph by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard News Office

Yu Kongjian, a visiting professor at the Graduate School of Design, led the Harvard delegation on a walking tour of the still unfinished Expo 2010, the Shanghai's world fair opening on May 1.

Shanghai Urban Development

An afternoon bus tour organized by GSD dean Mohsen Mostafavi for alumni, faculty, students in Yu Kongjian’s studio course (and his fellow teachers), and President Faust and her husband, Charles Rosenberg, Monrad professor of the social sciences, began with narration by lecturer in urban planning and design Bing Wang. She noted that Shanghai is, by Chinese standards, a young and atypical city: it was established just 400 years ago, as a fishing village and trading port for Suzhou. It had none of the features of a politically significant city (which would have been built around a government center and a Confucian school complex). From the outset, it was a commercial outpost (of lesser social significance in imperial China); and after the European treaty ports were established in the 1840s, an increasingly significant one. That history, she said, shaped Shanghai’s role today: as a center of commerce and finance; and as the major Chinese city most open to the world outside, most porous to other influences.

Photograph by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard News Office

President Faust and other members of the Harvard party also viewed a model of the Expo 2010 site.

The Harvard party entered the world’s fair site, very much under construction, and walked along the new Shanghai Houtan Park, a linear waterfront park parallel to the Huangpu River, designed by Yu Kongjian to reclaim an industrial wasteland and remake it into a demonstration ecological site, planted with indigenous species—an unusual green outpost in the middle of an ever-more-relentlessly developed urban setting.

En route to the city’s urban-planning exposition site—centered on an enormous model of the development envisioned during the next decade—Bing Wang described the changes that had shaped urban land markets. Following nationalization after the communist victory in 1949, she said, market reforms were first introduced in 1998. The government began involving private developers to build on sites, and state-owned enterprises stopped providing housing to their workers (housing units were sold, but the government retained land ownership). More substantial ownership rights were introduced in 2008, she said. In Shanghai and other cities, skyrocketing land and housing prices (a result of loosened controls and tremendous economic growth) now resulted in rising public protests, and emerging discussion of new ways to rein in the markets and provide public support for housing.