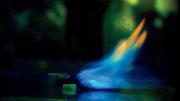

Three years ago, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) laid down a challenge to scientists: find a way to use electric fields or sonic waves to suppress fire instantly. “Fire, especially in enclosed military environments such as ship holds, aircraft cockpits, and ground vehicles, continues to be a major cause of material destruction and loss of warfighter life,” noted the agency in its announcement. This spring, scientists in the lab of Flowers University Professor George Whitesides succeeded in extinguishing a flame a foot and a half high with a strong electric field.

A flame, explains Ludovico Cardemartiri, the postdoctoral fellow who ran the experiments, is really a chemical reaction in which part of the combustible fuel source is being ionized—separated into positively and negatively charged particles that form a gas cloud of charged particles called a plasma. That much has been known for a long time, and scientists have even used static electric fields to “bend” flames.

The Whitesides team found that by using an oscillating electric field (of the kind generated by alternating current), rather than a static field, the flame could actually be snuffed out. Because a flame is a complex system, composed of myriad dynamic parts, Cardemartiri explains, scientists still don’t have a complete quantitative understanding of this process. But they think that the soot in the flame might play an important role, by concentrating the positively charged ions in the plasma; when a high-voltage electric field emanating from the tip of a wire is pointed at the flame, it exerts a repelling force on the charged particles, which drag the plasma with it. Pushed off its fuel source, the flame dies.

Whether this discovery will yield fire-suppression technologies of the kind that DARPA hopes for remains to be seen. Nevertheless, Cardemartiri points out that this kind of basic research, which has yielded new insight into how electrical waves can control flames, could have an impact on other important applications of combustion—perhaps even in cars or power plants.