Harvard reported a $130-million operating deficit in the fiscal year ended last June 30—about 3 percent of total expenditures—according to the Harvard University Financial Report released on October 28. Although the report characterized the deficit as “not unexpected,” it followed essentially break-even results (a deficit of $0.9 million) in fiscal 2010—the first full fiscal year following the financial crisis of late 2008 and the ensuing recession. (In 2008-2009, the $11-billion decline in the value of the endowment caused the University to retrench and to begin reducing subsequent distributions from the endowment to support the operating budget—an effect that diminished the largest single source of revenue in fiscal 2010 and 2011.)

Characterizing the year in a conversation, Daniel S. Shore, vice president for finance and chief financial officer, noted that Harvard was “still adapting our operations” to the reduced endowment and operating distributions. Those adaptations involve taking steps to enhance efficiencies and reduce costs “with urgency, but a thoughtful urgency”—for example, multiyear transitions to new administrative structures and processes for the large library system, and consolidated information-technology operations. The changes also include making “very significant progress” on measures to lessen the University’s financial risk by moving toward a better debt structure and greater liquidity overall, among other steps (see discussion in “The Balance Sheet,” below).

Following a year during which expenses grew more than four times as fast as revenues, the actions Shore described are taking place in an environment of revenue growth that he said he expects will “continue to be sluggish.” That will put pressure on Harvard’s reported financial results, even as it pursues increased spending on priorities ranging from financial aid to new academic and research programs for which permanent funding has not yet been secured.

The Altered Revenue Environment

For fiscal 2011, revenue increased 1 percent (approximately $39 million) to $3.78 billion, from $3.74 billion in the prior year. Sources of increased revenue included:

- a $66-million (nearly 11 percent) increase in federally sponsored research support, to $686 million (reflecting both Harvard’s research prowess and the availability of economic-stimulus funding for research grants);

- a $29-million (4 percent) gain in revenue from students—tuition and fees—after taking into account increases in scholarship spending, led by the $18-million (7.5 percent) increase in continuing- and executive-education programs; and

- the 12 percent increase in current-use giving (to $277 million).

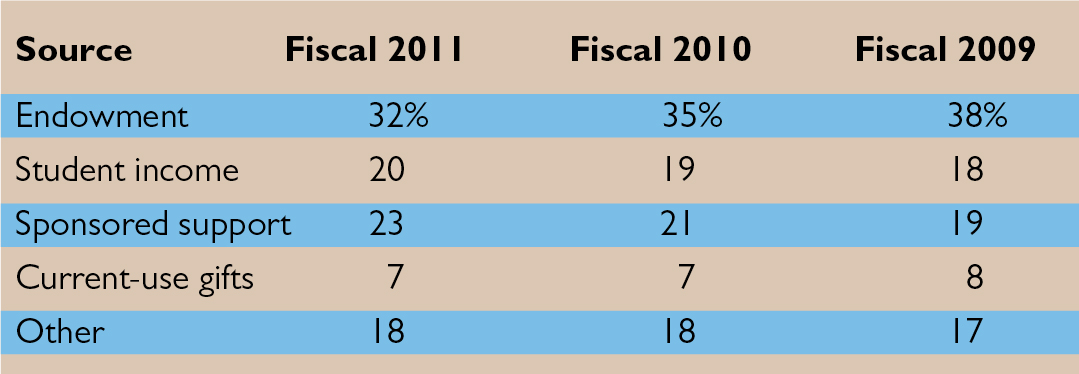

In the aggregate, those factors increased revenue by $124 million—nearly offsetting the $129-million decline in distributions from the endowment for operating purposes. That decrease (nearly 10 percent) followed a 7 percent reduction in fiscal 2010. Since peaking at $1.42 billion in fiscal 2009, the endowment distribution for operations has declined by $224 million. (During the same period, other income distributions from University funds held in the “general operating account” have also declined, from $166 million in fiscal 2009 to $157 million in the subsequent year, and $148 million in the latest period.) The result has been a significant change in the University’s revenue stream, with a lessened reliance on endowment distributions and greater reliance on sponsored-research funding and student tuition and fees (even with rising financial aid):

In the longer term, the events of the past few years have raised fundamental questions about Harvard’s finances, as highlighted in President Drew Faust’s message in the report. As she summarized matters:

Changing financial realities require an ongoing examination of our funding model with its reliance on government support, endowment returns, and tuition—all of which are expected to be either declining or constrained in the years ahead.

Hence the emphasis in the financial overview prepared by Shore and treasurer James F. Rothenberg, a member of the Corporation, who stress the importance of “pursuing a number of strategies that will help to reduce ongoing costs and enable high-priority reinvestment in the years ahead.” They also allude in separate passages to nascent initiatives to “explore the potential of generating additional revenue” and measures “to achieve further diversification in our revenue base.”

Expenses

Harvard’s expenses in fiscal 2011 rose a reported $168 million—about 4.5 percent (or somewhat more than that, taking into account the one-time expense of spinning off the Broad Institute in fiscal 2010, with an associated charge of $52 million). The major factors increasing expenses included:

- compensation costs, which rose $92 million (5 percent), with salaries and wages $57 million higher (4 percent)—as the salary and wage freeze of fiscal 2010 ended, staffing grew along with sponsored-research grants, and some additions were made in faculty and other ranks—and benefits costs swelled 8 percent ($35 million); and

- debt-service costs, which went up $33 million (12 percent), to $299 million—nearing 8 percent of total expenses—reflecting both a higher volume of debt outstanding during much of the year, and a shift from floating-rate to fixed-rate obligations (see "The Balance Sheet," below).

Shore said that even though the University has been pursuing cost-cutting measures, it “can’t keep [growth in] expenses below the rate of inflation indefinitely” (and some of the rise in expenses, of course, is associated with higher sponsored funding for research).

Capital spending, which had been essentially cut in half, to $324 million, in fiscal 2010, declined further, to $314 million in the last year. Two of the major projects under way during fiscal 2011—the refitting of the Sherman Fairchild biochemistry building for stem-cell scientists and the new Law School building—have been completed, or will be finished by the spring. Work continues on the major Harvard Art Museums expansion. The most significant construction project on the horizon is the Business School’s Tata Hall (an executive-education facility scheduled to break ground next month).

Shore outlined several priorities aimed at managing expenses. One is implementing an “enterprise procurement system” to aggregate purchasing power, putting Harvard in a position to strike better deals with vendors; although the University already designates preferred vendors, its decentralized structure makes maximizing economies of scale difficult. This is an example, Shore noted, of the up-front investments the University must incur to achieve long-term gains; the new library structure and processes, and the information-technology reorganization, are other prominent cases.

Both the report itself and Shore in conversation highlighted escalating employee-benefit costs, which have now compounded at a 10 percent annual rate during the past decade. (Benefits expense now equals 32 percent of salaries and wages, up from 20 percent in fiscal 2011.) The University’s health benefits for calendar year 2012 maintain modest growth in premiums, but introduce significant increases in employee co-payment, deductible, and maximum out-of-pocket spending schedules (particularly for retirees). Shore characterized the announced changes in plan design as “modest,” and emphasized the need for more significant changes in the future to restrain benefits-expense growth, particularly in light of his expectations for slight revenue increases.

The Balance Sheet

The 2008 financial crisis impelled Harvard’s leaders to reduce the University’s exposure to financial risks across the board. The fiscal 2011 report provides further evidence of how substantially the institution’s financial structure has been changed—a process described in the fiscal 2010 report as “de-risking” and embracing greater liquidity, less reliance on floating-rate debt, reduced exposure to interest-rate swaps, and changes in the endowment investment portfolio. During the most recent fiscal year:

- Harvard further augmented its liquid operating funds ($300 million at the end of fiscal 2008, $1 billion at the end of fiscal 2010, and $1.1 billion on June 30, 2011), rather than investing almost all of them alongside the endowment and risking cash-flow problems and large losses like those encountered in the autumn of 2008.

- The University trimmed variable-rate bonds, notes, and commercial paper outstanding from $2.4 billion (62 percent of the total $3.8 billion of obligations) at the end of fiscal 2007 to just more than $600 million (less than 10 percent of the total $6.3 billion of debt outstanding) at the end of fiscal 2011. That debt restructuring sharply reduces exposure to interest-rate spikes and minimizes any chance that the University could find itself unable, in a period of market turmoil, to roll over short-term borrowings, forcing it to scramble for funds.

- Harvard also pared its interest-rate swaps. Following the surprise loss of $1 billion on interest-rate exchange contracts in fiscal 2009, the University entered into offsetting swap contracts during fiscal 2010 that enabled it to contain exposure to further losses. During fiscal 2011, when interest rates were temporarily at favorable levels, Harvard made cash payments totaling $278 million to terminate more of the swap agreements, enabling it to end the year with remaining losses over the life of such contracts locked in at a readily manageable level of about $400 million.

- And as reported, Harvard Management Company continues to work down its future commitments to convey endowment funds to outside advisory firms for investment in illiquid categories of assets. Those uncalled capital commitments had ballooned to $11 billion at the end of fiscal 2008, when the endowment was at peak value; the financial report details a continuing decline, to $5.4 billion at the end of fiscal 2011 (from $6.6 billion a year earlier).

Moreover, the report notes, in June, Harvard redeemed $300 million of the debt that had been issued in late 2008, when the University was under the greatest pressure from the financial crisis. Without that redemption and the cash payments to extinguish some of the interest-rate swaps—long-term measures that reduce leverage and exposure to risk—Harvard conceivably could have ended fiscal 2011 reporting liquid operating funds on its books of $1.7 billion, rather than $1.1 billion.

The Outlook

During fiscal 2011, Shore said, Harvard funded its operating deficit with “accumulated surpluses that the University has earned in the past”: endowment income distributed but not yet spent, gift and sponsored-fund grants received but not yet applied to operations. They are, in effect, the “bridging mechanism” until long-term measures to reduce expenses are fully in place—and while revenue growth is very low, allocations for financial aid and other priorities increase, and planning proceeds for a capital campaign that (it is hoped) will provide permanent support for such initiatives.

What is the near-term outlook?

Endowment. Significantly, after two years of reductions in endowment distributions, the Corporation authorized an increase in such distributions during the current fiscal year (approximately 4 percent, plus any growth brought about by new gifts for endowment that contribute to operating revenue during the year—in total, perhaps $50 million to $70 million in increased revenue during fiscal 2012). The financial report indicates that a further increase is planned for fiscal 2013, beginning next July 1; the amount of that increase has not been disclosed.

For the past two fiscal years, Shore said, the Corporation has determined the future endowment distribution using a so-called “smoothing rule” that adjusts gradually for large swings in endowment value (in either direction), in place of a more informal rule of thumb. That has the effect of sustaining University operations despite a severe decline in endowment value, like that suffered in fiscal 2009, and taking advantage only gradually of the occasional very strong recovery years, like the one just ended (when Harvard Management Company achieved a 21.4 percent investment return on endowment assets, bringing its value to $32 billion—still about $5 billion below its peak value in fiscal 2008).

(Atop the operating distribution, the Corporation typically authorizes “decapitalizations” from the endowment for specific or one-time purposes. These totaled $235 million and $237 million, respectively, in the past two fiscal years. In fiscal 2010, the half-percent annual levy for the “administrative assessment” for expenses associated with Allston campus development accounted for about $130 million of that sum; by formula, the Allston assessment should have increased modestly in 2011, and would rise further this year.)

Sponsored funding. Research grants may in part offset the higher endowment distribution this year. According to the annual report, Harvard had been awarded 310 grants from the incremental research funds authorized as part of the federal economic-stimulus program, for a total of $240 million. Through last June 30, $134 million of those funds had been spent, with the remainder to be used chiefly in fiscal years 2012 and 2013. As those funds are used, Harvard researchers’ success in winning new grants from continuing programs will determine whether sponsored funding continues to augment University revenues, or becomes a drag on the top line. (Through the early months of the current fiscal year, Shore indicated, grant awards continued to increase.)

Expenses. Compensation costs—salaries, wages, and benefits—are of course likely to increase during the year. But interest costs—the other significant factor in increasing expenses during fiscal 2011—in fact should level off, given that the restructuring of debt obligations has already taken place, and the amount of debt outstanding will, on average, be lower in fiscal 2012 than the total during last year.

Fiscal 2012. According to conventional wisdom, institutions mounting capital campaigns like to present balanced budgets: donors don’t want to be solicited to fund operating deficits. Shore noted that the University is incurring expenses to effect future cost savings (as described above), and is spending on urgent priorities (from financial aid to new doctoral programs) as warranted. It is doing so while “dealing with whatever the world gives you”—in this case, negligible revenue growth while Harvard acclimates itself to the downsized endowment.

As chief financial officer, he said, he would be happiest knowing that operations would be on a break-even basis this year, but too many uncertainties exist this early to know whether Harvard will do so, or will report a deficit again for fiscal 2012. The University’s plans, he said, take into account:

- “continuing pressure on the capital markets,” with volatile returns and possibly adverse effects on the endowment, as signaled by Harvard Management Company president and CEO Jane Mendillo in September;

- “continuing pressure on the federal budget,” with possible adverse effects on research funding, nonprofit institutions’ tax-exempt status, and the tax deduction for charitable giving;

- continuing community needs in Boston and Allston, with implications for local taxes and spending;

- the obligations imposed by “big, fixed-cost infrastructure” common to Harvard and other research universities, “with elements of deferred maintenance” and deferred modernization of classrooms, laboratories, and other facilities for current use; and

- within the immediate Harvard community, the sense that the recent robust endowment returns imply a “back to normal” environment, when in fact the endowment remains one-sixth smaller than its value in fiscal 2008—and the operations it then funded have not been fully resized to reflect current realities.

Shore said he did not expect “supersized” endowment returns, like those in fiscal 2011, in the future. His outlook for revenue from government sources is “quite cautious”—and those two sources account for about half of Harvard’s revenue. The University, he said, “certainly would not add material amounts” of debt to its current borrowings, even given current low interest rates (and even if rating agencies would extend their AAA/Aaa credit rating for a more-leveraged University). A lesson of the financial crisis, he said, was that an institution with large fixed costs, like Harvard, should be wary of incurring a heavily debt-laden balance sheet.

Accordingly, Shore said, “We need to do a whole menu of things to help stay financially robust,” from the administrative improvements under way or planned, to better containment of benefits costs, to exploring “all kinds of new revenues,” to the philanthropic support a campaign would encourage.