He was the son of a black slave and a renegade French aristocrat, born in Saint-Domingue (now Haiti) when the island was the center of the world sugar trade. The boy’s uncle was a rich, hard-working planter who dealt sugar and slaves out of a little cove on the north coast called Monte Cristo—but his father, Antoine, neither rich nor hard-working, was the eldest son. In 1775, Antoine sailed to France to claim the family inheritance, pawning his black son into slavery to buy passage. Only after securing his title and inheritance did he send for the boy, who arrived on French soil late in 1776, listed in the ship’s records as “slave Alexandre.”

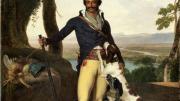

At 16, he moved with his father, now a marquis, to Paris, where he was educated in classical philosophy, equestrianism, and swordsmanship. But at 24, he decided to set off on his own: joining the dragoons at the lowest rank, he was stationed in a remote garrison town where he specialized in fighting duels. The year was 1786. When the French Revolution erupted three years later, the cause of liberty, equality, and fraternity gave him his chance. As a German-Austrian army marched on Paris in 1792 to reimpose the monarchy, he made a name for himself by capturing a large enemy patrol without firing a shot. He got his first officer’s commission at the head of a band of fellow black swordsmen, revolutionaries called the Legion of Americans, or simply la Légion Noire. In the meantime, he had met his true love, an innkeeper’s daughter, while riding in to rescue her town from brigands.

If all this sounds a bit like the plot of a nineteenth-century novel, that’s because the life of Thomas-Alexandre Davy de la Pailleterie—who took his slave mother’s surname when he enlisted, becoming simply “Alexandre (Alex) Dumas”—inspired some of the most popular novels ever written. His son, the Dumas we all know, echoed the dizzying rise and tragic downfall of his own father in The Three Musketeers and The Count of Monte Cristo. Known for acts of reckless daring in and out of battle, Alex Dumas was every bit as gallant and extraordinary as D’Artagnan and his comrades rolled into one. But it was his betrayal and imprisonment in a dungeon on the coast of Naples, poisoned to the point of death by faceless enemies, that inspired his son’s most powerful story.

The true story of Alex Dumas was itself ruthlessly suppressed by his greatest enemy—and remained buried for 200 years. In fact, Dumas became not merely a great soldier of the French Revolution but also the highest-ranking black leader in a modern white society before our own time—by the age of 32 he was appointed commander-in-chief of the French army in the Alps, the equivalent of a four-star general. The young general from the tropics led 53,000 men in fierce glacier fighting against the best alpine troops in the world and captured the mountain range for France. (Not content with overthrowing their own rulers, the French revolutionaries had declared a “war of liberation” on all their neighbors.) And though the Austrians nicknamed him der schwarze Teufel—“the Black Devil”—he was an angel to victims of oppression, no matter their side: in the midst of the Revolution’s bloody chaos, he pushed back against those committing terror, earning the mocking nickname “Mr. Humanity” and narrowly escaping the guillotine himself.

Dumas’s incredible ascendancy as a black man through the white ranks of the French army reflected a key turning point in the history of slavery and race relations as forgotten as Dumas himself: a single decade when revolutionary France ended slavery and initiated the integration of its army, its government, and even its schools. General Dumas was “a living emblem of the new equality,” wrote a nineteenth-century French historian—but his career’s tragic unraveling reflected the unraveling of that progress as well.

The agent of destruction for both was his fellow general, Napoleon, who at first praised Dumas as a Roman hero for his battlefield feats but came to loathe him for his independence and revolutionary values. The two men clashed in 1798, during the invasion of Egypt—where the Egyptians mistook the towering Dumas for the leader of the French forces. Then, while Dumas languished for two years in an enemy dungeon, Napoleon made himself dictator and dismantled France’s postracial experiment, imposing cruel race laws in France, reinstituting slavery in the colonies, and sending an invasion force to Saint-Domingue with orders to kill or capture any black who wore an officer’s uniform. He went to equally extraordinary lengths to bury the memory of Alex Dumas, thundering, “I forbid you to ever speak to me of that man!” when former comrades tried to intervene on behalf of the general and his family, who were living in near-destitution. Barely five years after his return to France, Dumas died at 43 of stomach cancer, likely an aftereffect of his poisoning while imprisoned.

Dumas’s son, the future novelist, would take a marvelous sort of revenge, infusing his father’s life and spirit into fictional characters who have been embraced the world over. Yet while every generation has heaped glory on the name Alexandre Dumas, the great general has remained forgotten. The only statue of him—in a country awash in marble generals—was erected in Paris more than a hundred years after his death, and then destroyed by the Nazis.