Art dealer Judy Goffman Cutler began collecting American illustrations in the early 1970s with a few pen-and-ink drawings by Charles Dana Gibson. His “Gibson Girl,” created in the 1890s, was a well-born, statuesque, “ideal woman” who helped sell magazines and fashions for two decades—until he fell out of vogue. Gibson’s exquisite renderings, like other popular illustrations that followed, says Cutler, were “denigrated as ‘commercial art’: if you were paid for your work, you were not considered a real artist.”

Now the owner of the American Illustrators Gallery in Manhattan, Cutler is an expert on the genre and has nearly 5,000 original oil paintings, watercolors, and drawings by artists ranging from Gibson and Howard Pyle to N.C. Wyeth, Maxfield Parrish, J.C. Leyendecker, and Norman Rockwell. More than a hundred of the best are on display at The National Museum of American Illustration, which Cutler and her husband, Laurence S. Cutler, M.Arch. ’66, M.A.U. ’67, co-founded and run at their Newport, Rhode Island, mansion.

The collection reflects the “Golden Age of American Illustration,” from the 1880s to the early 1950s, when these artists’ handiwork was reproduced in books, periodicals, and advertisements. The age marked not only the birth of commercialized graphics, but a seismic industrial and cultural shift that presaged the marketing and branding industries and, in fact, the era of mass-media communications. It was also a boon for easel-trained artists who, for the first time, could be assured of lucrative and steady work.

“People don’t know what illustration was,” asserts Judy Cutler, “or that most of these artists were classically trainedas fine artists.” The museum addresses both points—and provides the grandest of settings to show off the (still-growing) collection. “She’s a hoarder,” Laurence Cutler says of his wife, who laughs and nods. The Cutlers grew up in Woodbridge, Connecticut, and have known each other all their lives; actress and comedienne Whoopi Goldberg (a friend, and longtime illustrator collector herself) calls their banter “the Laurence and Judy show.” Each married and divorced others before tying their own knot in 1995.

Cutler says he “lucked out” with a hoarder who saw the art’s intrinsic value despite the fact that people “were selling original Gibson drawings by the stack, by the pound. Judy recognized that these illustrators were important because they tell our American history—in images. The interesting question,” he allows, “is whether the illustrators reflected American society, or whether they, in fact, shaped and influenced society, along with our perceptions of it.”

The museum fills two floors of the couple’s regal manor, Vernon Court—itself an American artifact. The Beaux-Arts adaptation of a French château on Bellevue Avenue was designed and built in 1898 by Carrère and Hastings, the architects of the New York City Public Library. The Cutlers bought it in 1998 and, following repairs and restoration work, opened the museum to the public two years later. “Visitors here,” claims Judy Cutler, “get two for the price of one: a tour of a beautifully restored Gilded Age mansion and a close look at the greatest illustrators of the Golden Age.”

Ideally, a visitor would take at least a week to absorb what’s on show. The art is hung, salon-style, amid gilded moldings, marble floors and fireplaces, chandeliers, and carved and brocaded period French furnishings. “It’s all the stuff we were taught to hate at the Graduate School of Design,” jokes Laurence Cutler, a retired architect and former assistant professor at Harvard who has since come to love it. The Rose Garden loggia, with arched glass doorways leading outside, features sections of Maxfield Parrish’s largest and most extensive work, the 18-panel mural A Florentine Fete. Painted between 1910 and 1916, the panels were first displayed in the “Girls Dining Room” at Curtis Publishing in Philadelphia, then-owners of Ladies Home Journal. Parrish put himself into the Fete, and a close look reveals that nearly every woman is a version of his longtime model and mistress, Susan Lewin. “She appears 166 times,” Laurence Cutler notes. “I counted.”

Parrish’s splashy party-goers, draped in medieval-style gowns, robes, and costumes, are lounging under lapis lazuli skies, amid classical archways, stone staircases, and the odd Grecian vase. The layering and luminous effects of color, the painstaking details, and the sense of playfulness and freedom are enchanting. The viewer’s attention roams among laughing faces, couples talking tête-à-tête, and a handful of characters dressed in striped and checkered garb. In one setting, a provocative Lewin stands front and center dressed in a Robin Hood-esque outfit, albeit with a short skirt and boots. Three panels that failed to fit in the loggia fill the walls above a graciously winding staircase to the second floor (shown in the photo gallery accompanying this article).

The Fete stays put. But Judy Cutler rotates other works, curating a few special exhibits each summer. This year, along with a July 30 gala to benefit the museum (tickets are on sale through the website), she has organized Rockwell and His Contemporaries. His famous Miss Liberty (1943) will be on view, along with art by Stevan Dohanos. Another veteran Saturday Evening Post illustrator, his precise realism—as well as a winking sense of irony—often rivaled Rockwell’s. Also in the show is the oil painting for a Post cover, A War Hero Telling Stories (1919), and other works by J.C. Leyendecker, an artist especially dominant in men’s fashion advertising, whom Rockwell consciously emulated; after finishing his own art studies in 1915, Rockwell even moved to Leyendecker’s town, New Rochelle, New York. The two corresponded for years before Leyendecker’s death in 1951. “Just as Rockwell ‘obsessed’ over Leyendecker, in a positive way, to learn how he painted,” Cutler says, “so did Rockwell’s contemporaries ‘obsess’ about Rockwell—like John Falter and other illustrators who then followed Rockwell around.”

Elsewhere around the museum, works are often grouped by themes. Depictions of pirates, trappers, and adventurers, for example, include N.C. Wyeth’s Archers In Battle andNorman Price’s Mary Reed (1929), both created for books, and Frank Schoonover’s To Build a Fire (1908) for the famous Jack London story published in The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine. Many of the same artists were enlisted to build support and funding for wars: Freedom Is Your Business (1950), by Howard Chandler Christy, was turned into a U.S. Army recruitment poster and Disabled Veteran (1944), by Rockwell, promoted war bonds. Rockwell’s Love Ouanga (1936), on the other hand, headlines the museum section on “race relations,” while his Russian Schoolroom (1967), which ran in Look, falls under “education.”

“The main job of these illustrators,” Laurence Cutler explains, “was to sell magazines and books and other products—which all sold more when they were illustrated.” This explosion of commercial graphics was made possible primarily by technological advances that enabled increasingly detailed images and an expanded color palette to be transferred from original fine art. Meanwhile, the rise of railroads allowed products and periodicals to become truly “national.” In 1872, according to Laurence Cutler, the country had roughly 800 newspapers, but by 1893 “there were 5,000. And then magazines started to proliferate, like Harper’s Weekly, Hearst, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper/Leslie’s Weekly and, most popular in its day, Century Magazine.”

By the late 1870s, the “father” of American illustration, Howard Pyle (1853-1911), was contributing to Scribner’s Magazine and Harper’s Weekly, and was especially known for illustrating (and sometimes retelling) fairy tales and adventure stories. More importantly, perhaps, late in life he founded and taught at the country’s first school for illustrators, thereby launching the careers of scores of students, such as Wyeth and Parrish, and influencing every generation of illustrators since.

Among those was the German-born, Paris-trained Leyendecker. Instrumental in the then-novel idea of an “advertising campaign,” he designed and defined an enduring collective vision of rugged but genteel manliness, using figures typically modeled on his companion, Charles Beach. The alluring “Arrow Collar” man starred in advertisements for Cluett Peabody & Company Inc.’s detachable collar between 1905 and 1931; the 1927 Interwoven Socks—Famous for Their Colors (part of a series for that company) features a strapping Scotsman in highland regalia—and argyles. So pivotal was Leyendecker’s work, adds Judy Cutler, that his 1914 Post cover Bellhop with Hyacinths almost single-handedly invented the tradition of sending flowers on Mother’s Day.

Parrish was so successful, reports Laurence Cutler, that he referred to himself as the “businessman with the brush,” and was the first artist to insist on the phrase “one-time use only” in his contracts. From 1918 through 1934, Parrish illustrated the hugely popular “Edison Mazda” calendars that advertised early light bulbs and lamps for General Electric. In the 1920s, Cutler continues, a Parrish calendar and/or copies of his most famous painting, Daybreak (1922), hung in a quarter of American households.

What’s remarkable about the original works from which, in some cases, millions of copies have been made, is the depth of talent and creative vision that’s not typically associated with commerce. Wyeth’s The Doryman (1933), printed in Trending Into Maine, a tribute by Kenneth Roberts, is simply a beautiful painting: faint sunlight plays amid rosy clouds and a blue sky that’s mirrored in the dark violet ocean waters; a stately white square farmhouse stands out on a distant green hill; and the rower’s arms and a seagull’s wings are cocked at the same angles, working in tandem as the day is winding down. “The whole Wyeth family has been on the coast of Maine for generations,” says Laurence Cutler, “and to me he captures something essential about the place.” Wyeth himself reportedly considered it among his best works.

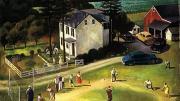

John Falter’s Family Picnic (1950), created as a Saturday Evening Post cover, depicts a late afternoon baseball game on a field that’s surrounded by a farmhouse, a river, and golden hayfields; the scene is more modern and Edward Hopper-esque than most of Rockwell’s art. The single quiet image “says so much about the American experience,” Cutler adds. Falter, who died in 1982, was among the last of the Golden Age illustrators. The advent of readily reproducible photography, and then color photography, slowly supplanted that era’s pioneering art form.

Interest in Golden Age illustrators, however, is alive. Attitudes changed within the last few years, especially since Rockwell’s Saying Grace brought $46 million at auction. “But they should have looked at illustration long before, for the high quality of the painting and the stories they tell,” Judy Cutler says. Abstract art doesn’t move her. “I don’t want to look at a Cy Twombly painting—can you image spending $22 million for a Cy Twombly and you see some gray paints running down a canvas?”

Falter’s June Wedding (1950), on the other hand, which hangs in the museum’s library room, portrays modest backyard nuptials, with lilacs in bloom and an old man in suspenders, en route home from the grocery store, who has stopped to watch the proceedings over a white picket fence. The timeless tradition, a sense of regeneration, is rendered in “intricate detail and wonderful colors,” Cutler says, “and you like it. It makes you smile.”