Every object tells a story, and most objects tell many stories. Some can help us transcend boundaries between people, cultures, and academic disciplines to discover crosscurrents in history. Allow me to make that argument by examining a common object, an “orphaned” sewing machine.

Several years ago, my colleague Ivan Gaskell and I decided it would be interesting to have students look at one of the landmark inventions of the nineteenth century—a sewing machine. The first sewing machines were patented about 1845. By 1900 they were as common as a cell phone might be today—and just as much a model of innovation and social transformation. When we couldn’t find a sewing machine in any of Harvard’s museums, I called a curator who had been cataloguing Harvard’s so-called “ephemeral collections,” things kept in offices, dormitories, or classroom buildings. She said Harvard did not have a sewing machine, but she did and she would be happy to let me use it.

(Click arrow at right to see images 1-3) Image 1

Photograph courtesy of Harvard University's Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments

Image 1

Photograph courtesy of Harvard University's Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments

Image 2

Photograph courtesy of Harvard University's Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments

Image 3

Photograph courtesy of Harvard University's Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments

It was quite a challenge to get it from her apartment to my classroom, but it was worth it. It was a beautiful thing (Images 1-3). But when I called to arrange for its return, the curator did not want it back; she was retiring and trying to downsize.

I could easily have sold that sewing machine on eBay or given it away. Instead I decided to find it a good home at Harvard. I consulted several museums and at least two libraries. Everybody thought it was a terrific object, but nobody really thought Harvard needed it. One museum thanked me for my generosity but said a sewing machine really didn’t fit their collections policy. Another said it was a marvelous example of technology, but that wasn’t the focus of their collection. The libraries said it was a lovely object and certainly related to many things in their collections…but no, they couldn’t take it. It was too big. Where would they put it? “We are a library, not a museum,” one astonished staff member said.

I understand all that. Not even an institution with as many tangible things as Harvard can accept everything anybody might offer. I nevertheless decided Harvard really did need a sewing machine. I just had to persuade someone to take it. Without question it relates to many of Harvard’s landmark museum and library collections. More important than that—it connects them. Sometimes a common object—an object so common that it ends up in flea markets—can actually connect aspects of history that far too often get separated in the way we think about and teach about the past. So I set about to expore possible connections between my object and Harvard’s many collections.

Image 4: Isaac Merrit Singer

Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery

I started with Harvard Business School. An entry on their own website told me that they needed a sewing machine. It told me that what is now Singer Corporation was one of the world’s first multinationals and that the company also helped bring the installment plan into marketing.

According to one scholar, the Singer sewing machine emerged from a collaboration “between a mechanical genius, Isaac Merrit Singer (Image 4), and a lawyer, Edward Clark.” Singer may or may not have been a mechanical genius, but he was a genius at keeping his own name in view: it appears at least five times on our sewing machine (Image 5). It is an appealing name: a sewing machine may not sing, but it certainly hums.

Image 5

Photograph courtesy of Harvard University's Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments

Image 6 Edward Clark

Courtesy of Harvard Business School

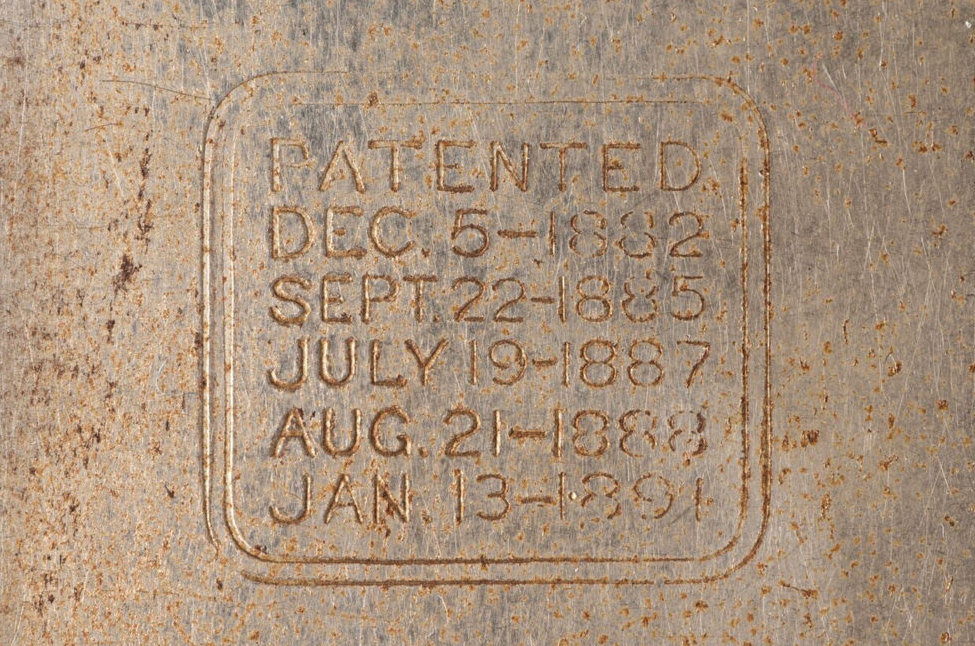

Lawyer Edward Clark (Image 6) played another role. As historian Nira Wickramasinghe explains, “The early history of the company…can be read as a maze of patent grabbing by a number of inventors….and subsequent litigation. No owner of a single patent could make a sewing maching without infringing on patents of others. Clark was instrumental in the creation of the Albany patent pool, where the holders of these key patents agreed to forgo litigation and to license their technology to one another.” Some sense of the importance of patents is seen on our sewing machine, which lists those from the 1880s to 1892 (Image 7).

Image 7

Photograph courtesy of Harvard University's Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments

The results were astounding. Singer opened its first foreign factory in Scotland in 1867. By 1914, it produced 90 percent of all sewing machine sales outside the United States and was the seventh largest firm in the world.

To understand the mechanical genius behind the sewing machine, let’s turn to the Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments and consider the work of Elias Howe (Image 8).

Image 8: Elias Howe

Courtesy of Harvard University's Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments

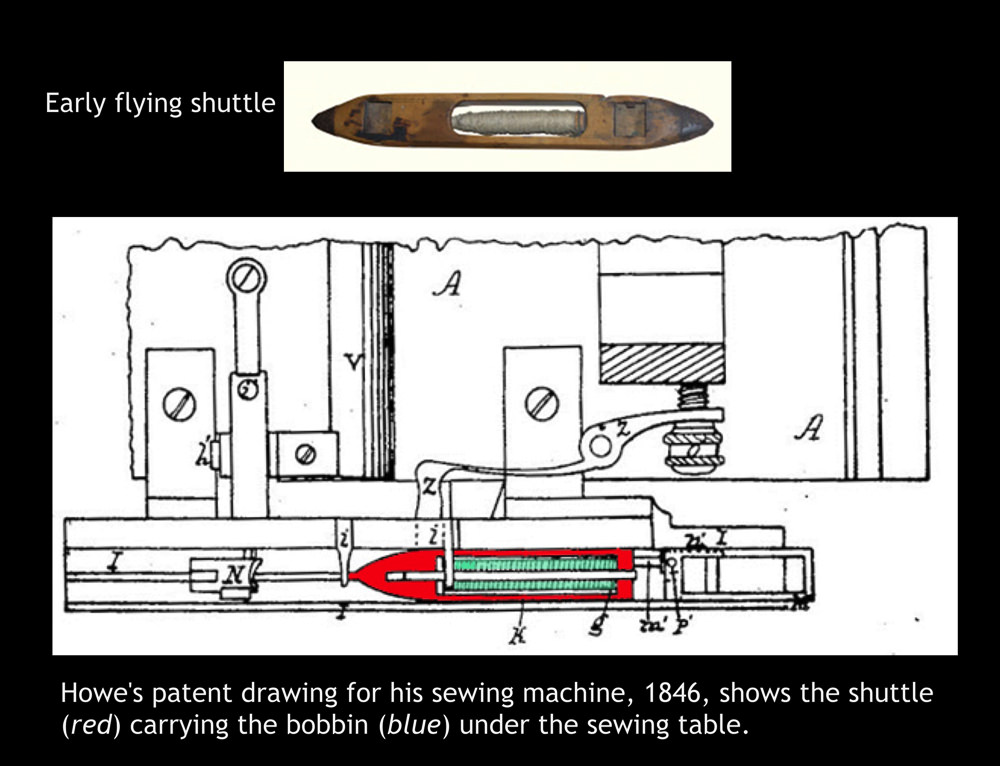

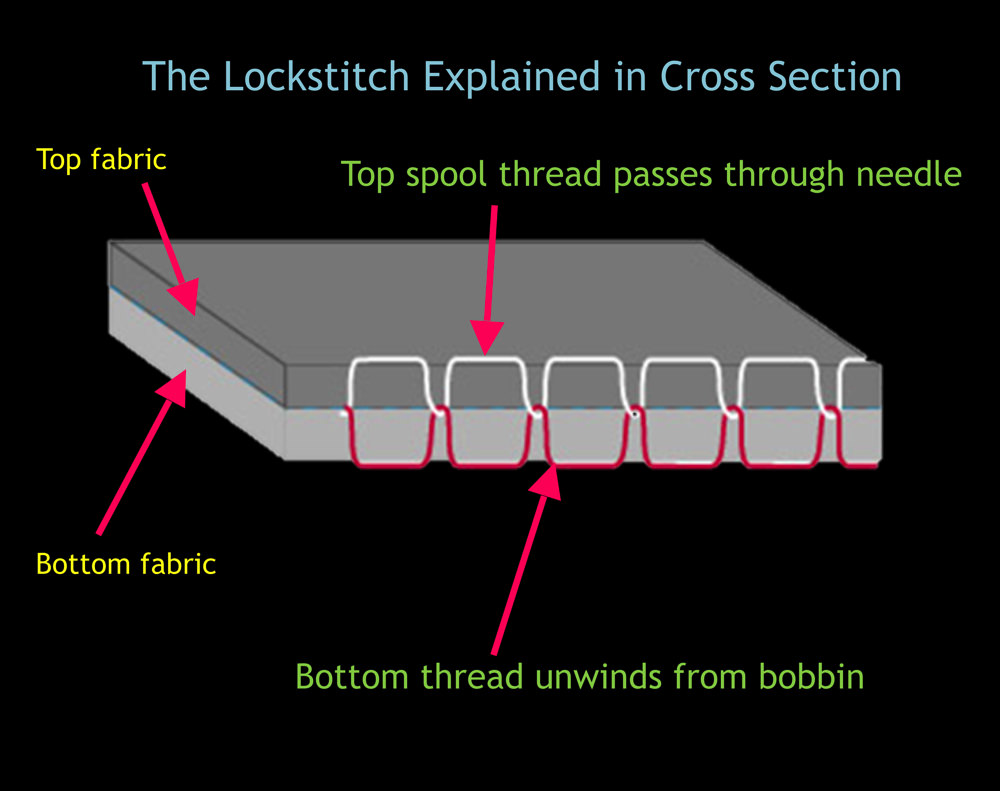

Howe contributed many things to Singer’s product (Images 9-12), including the use of a vertical needle threaded at the tip and the development of the shuttle that created the stitch.

Howe’s patent drawing is accompanied here by a drawing by Sara Schechner, Wheatland curator of the Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments, that explains how it worked. The shuttle is a miniature version of a weaver’s shuttle.

(Click arrow at upper right to see images 9-12) Image 9

Photograph courtesy of Harvard University's Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments

Image 9

Photograph courtesy of Harvard University's Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments

Image 10

Photograph courtesy of Harvard University's Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments

Image 11

Courtesy of Harvard University's Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments

Image 12

Courtesy of Harvard University's Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments

But perhaps our little machine could have a place in the Harvard Art Museums instead. Without question it belongs not only to commerce but to the decorative arts (Images 13-16).

(Click arrow at right to see images 13-15) Image 13

Photograph courtesy of Harvard University's Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments

Image 13

Photograph courtesy of Harvard University's Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments

Image 14

Photograph courtesy of Harvard University's Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments

Image 15

Photograph courtesy of Harvard University's Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments

Notice the elaborate designs on the end plates. The most dazzling element, however, are the two gilded sphinxes. The Harvard Art Museum has some prototypes of its own (Image 16).

Image 16

(Left top and bottom) Courtesy of Harvard University's Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments (Right top and bottom) Courtesy of Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum, bequest of David M. Robins

But in truth, our sewing machine is itself a sphinx. According to Greek mythology, a sphinx is a composite creature with the body of a lion, the wings of a bird, and the head of a human. Our machine has a body of iron, wings of wood, and a head that without question moves. It could be a post-modern sculpture.

A sphinx also produces riddles. Consider the little surprises and mysteries in the drawers (Images 17-19). On the left are spools of old thread and a much-used glob of beeswax In the right drawer, an intriguing box, when opened, reveals all the attachments for the machine.

(Click arrow at right to see images 17-22) Image 17

Photograph courtesy of Harvard University's Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments

Image 17

Photograph courtesy of Harvard University's Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments

Image 18

Photograph courtesy of Harvard University's Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments

Image 19

Photograph courtesy of Harvard University's Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments

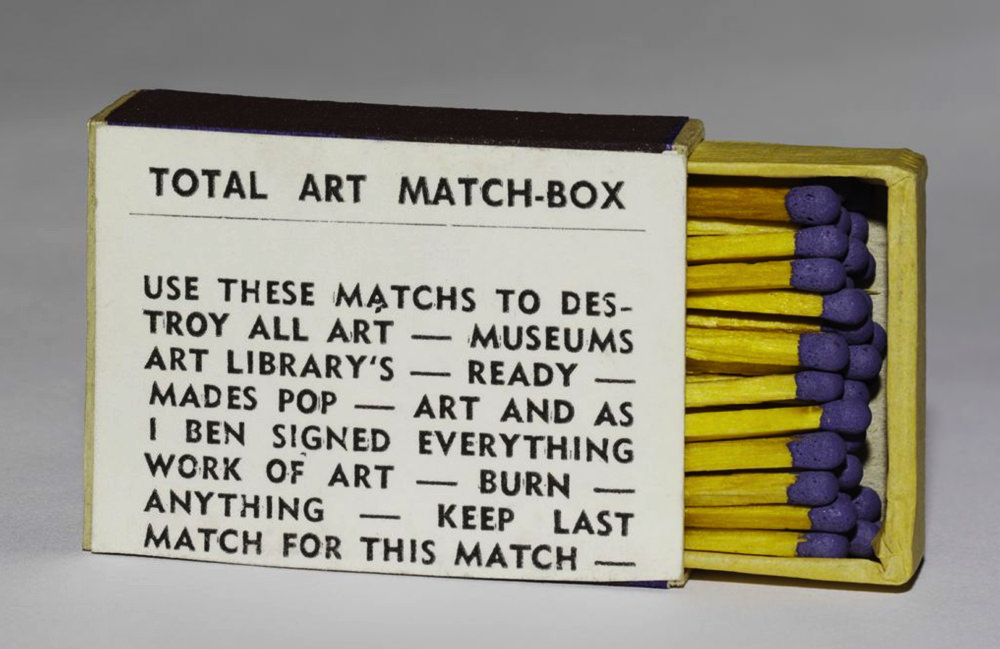

Image 20

Courtesy of Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Barbara and Peter Moore Fluxus Collection, Margaret Fisher Fund and gift of Barbara Moore/Bound & Unbound

Image 21

Courtesy of Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Barbara and Peter Moore Fluxus Collection, Margaret Fisher Fund and gift of Barbara Moore/Bound & Unbound

Image 22

Courtesy of of Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Barbara and Peter Moore Fluxus Collection, Margaret Fisher Fund and gift of Barbara Moore/Bound & Unbound

Amazingly, the Harvard Art Museum already has one of these boxes (Images 20-22). It arrived with a collection of objects associated with the so-called Fluxus movement of the 1960s, an effort by a loosely connected group of artists to challenge the boundary between art and life. Installing our orphaned sewing machine in the museum would certainly do that.

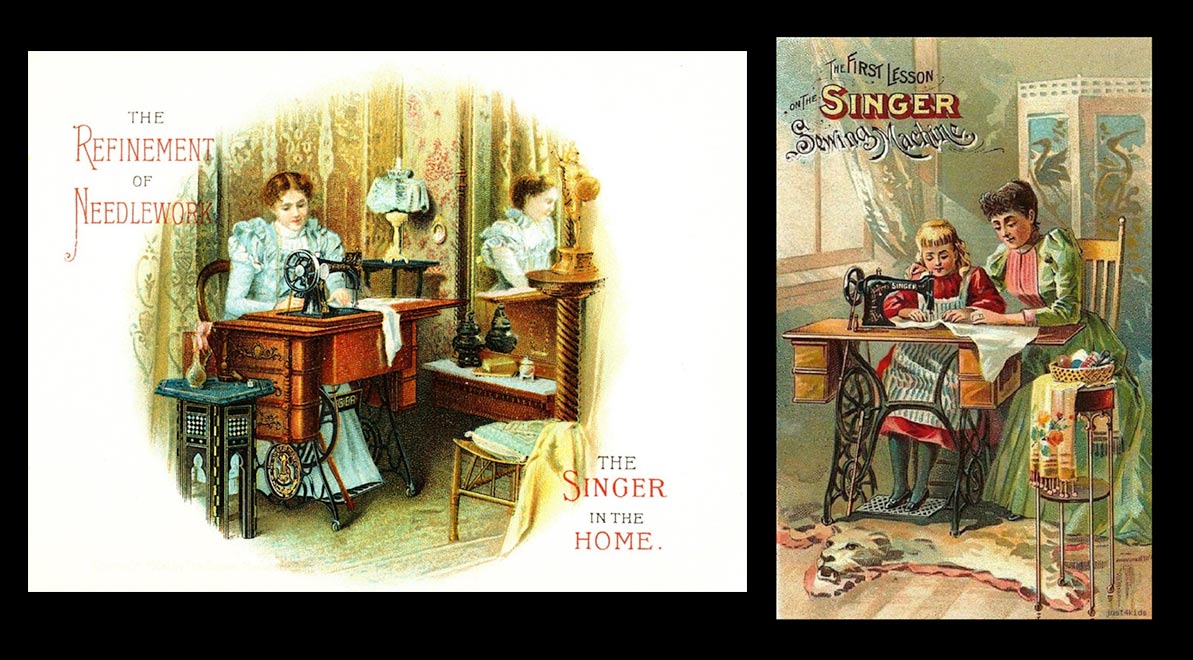

Image 23

Courtesy of Schlesinger Library

Or is the Schlesinger Library, which is devoted to the history of women in America (Image 23), a more logical fit? As the advertisement on the left shows, Singer marketed its machines to women not only to promote industry, but refinement. Mothers were to teach daughters, as my mother attempted—and failed—to do with me. Not every girl was adapted to sewing, as a witty essay by poet Maxine Kumin [’46, RI ’61,] reveals in her recollections of a sixth-grade sewing class presided over “by a supreme harridan named Miss Morrison.”

At the front of the room an oilcloth chart the size of a pull-down map of South America displayed the steps to be followed in threading this diabolical invention, the Singer sewing machine. This is my garbled recollection of the eight steps, as foreign to me as a Sanskrit text. First you set the spool on a little spindle, then you gingerly coaxed the thread end through one little eyelet, then you drew this spidery thread across the top to another eyelet, then down and around a small cog. Next you looped the thread… [and so on]. I could swim the Australian crawl, post to the trot, and smack a softball past third base, but I could not coordinate the flywheel and the treadle. My thread, so painstakingly arranged, broke and flew out of its settings. The bobbin thread, so assiduously wound, drawn up from its little coffin and conjoined with the needle, snapped free and retreated underground. Prisoner of clumsiness, I was told to begin again. “Follow the chart at the front of the room,” Miss Morrison said grimly.

At that point the befuddled sixth-grader threw up all over the machine. She claims that she never had to attend sewing class again.

Image 24

Courtesy of Schlesinger Library

Image 25

Courtesy of Schlesinger Library

Image 26

Courtesy of Schlesinger Library

Image 27

Courtesy of Schlesinger Library

Image 28

Courtesy of Schlesinger Library

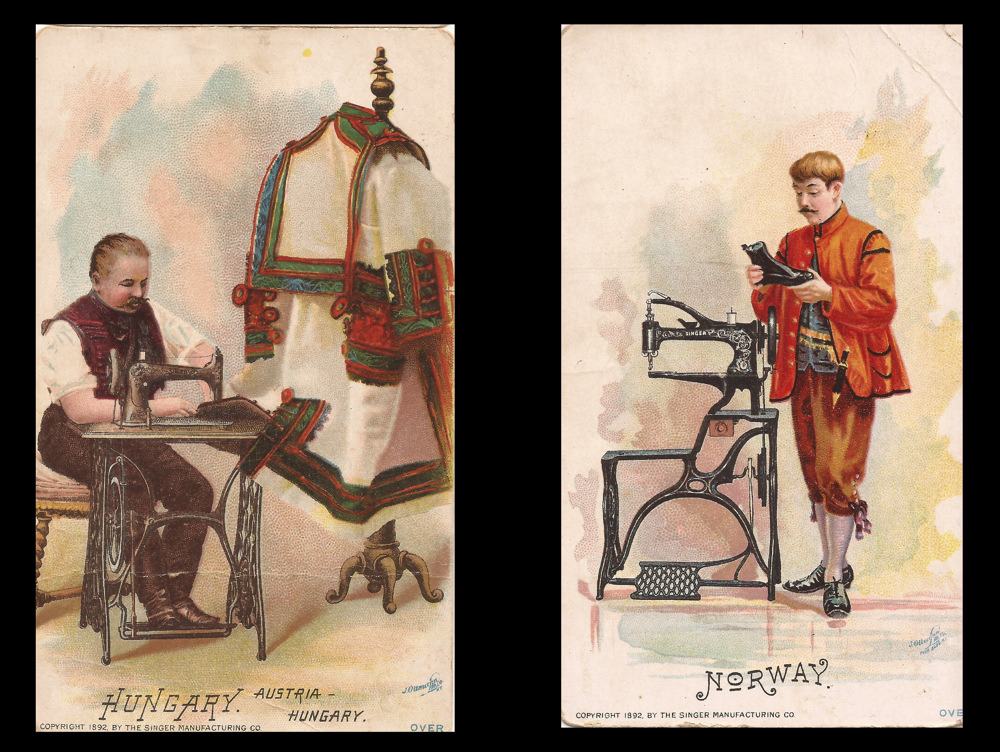

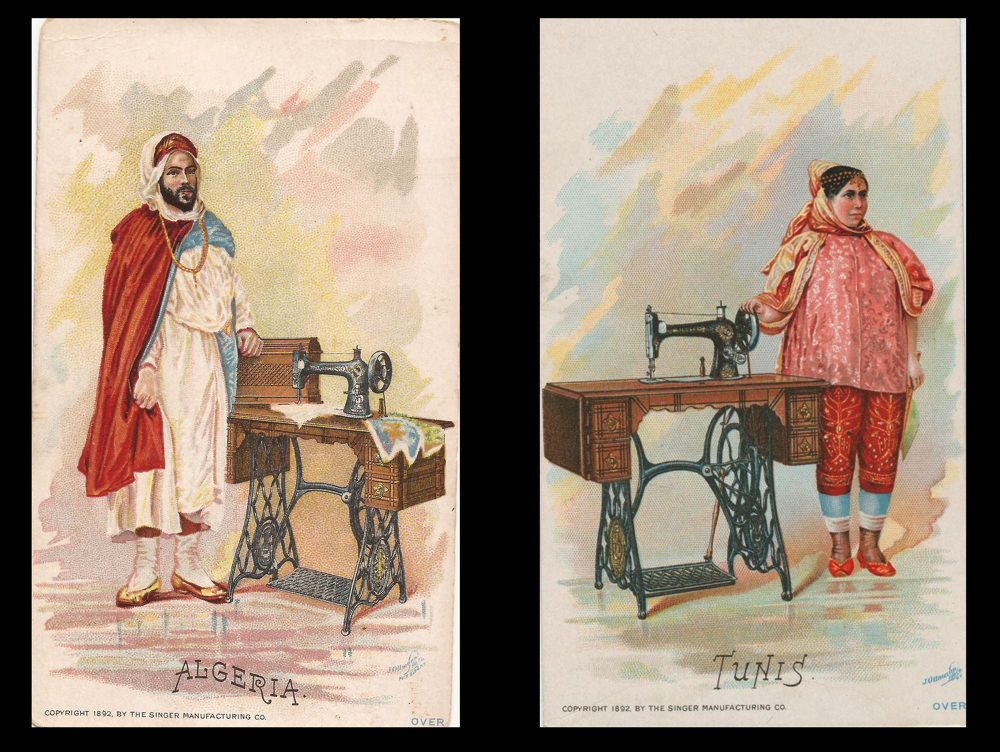

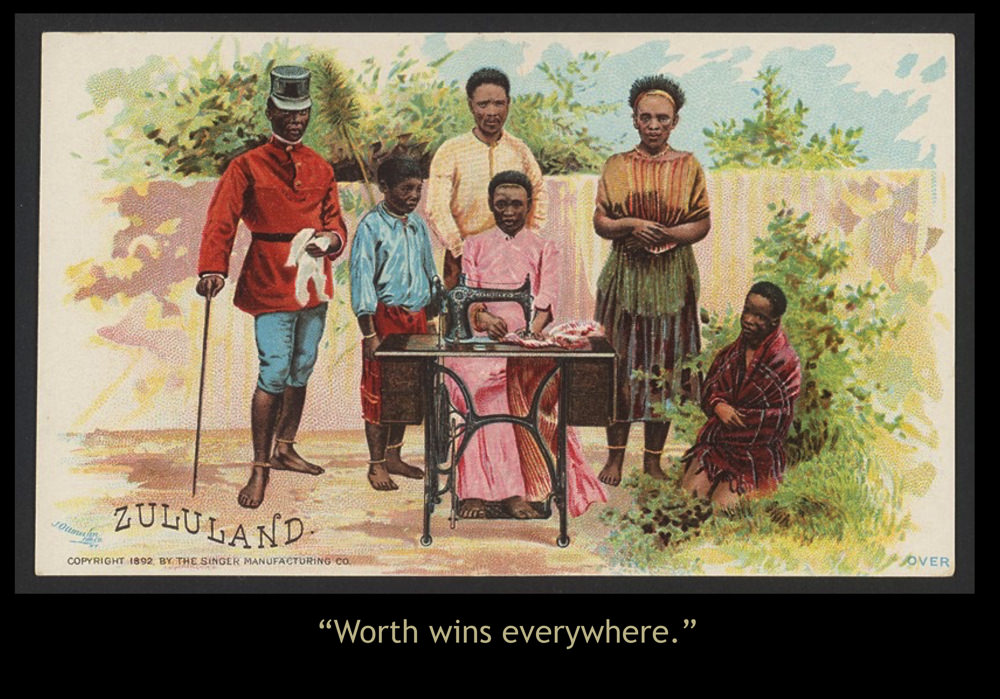

Among the more revealing of the Schlesinger items is a collection of trade cards that Singer initially produced for their exhibits at the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893 (Images 24-28). These were so popular the company continued the series for some years, handing them out to customers. This group shows how the ideal of womanly industry was seen as an international phenomenon The women supposedly wear national costumes, suggesting that the sewing machine is fully compatible with traditional and local values.

The trade cards sometimes feature men. The back of the HUNGARY card states: “The people show their Mongolian origin in their love for bright colors. This country tailor is embroidering a peasant’s state dress on the Singer Machine, which is extensively used in Hungary, where the Singer Company has 28 Offices.” The NORWAY card informs us that “The early history is enveloped in fable, the really authentic [history] beginning with ‘Fair-haired Harold’ in the Ninth Century.…Our picture represents a young Norwegian in the usual costume. His companion is The Universal Feed Machine, used in Shoe Repairing and Manufacture. Many of these machines, as well as thouands of our Family Machines, are sold yearly in the different cities of Norway.”

The trade cards also reach beyond Europe. The text on the back of the card featuring Algeria claims, “Even on this far off coast of Africa, the civilizing influence of our ‘Singer’ is felt, and our Agent has supplied the native as well as French inhabitants with thousands of Singer Machines.” The description of Tunis finds domesticity even in one of the “Barbary States.” Noting that Tunisian pirates were once “the scourge and terror” of the maritime world, it pictures “a Tunisian woman in her peculiar dress, resting her hand upon the woman’s faithful friend the world over….”

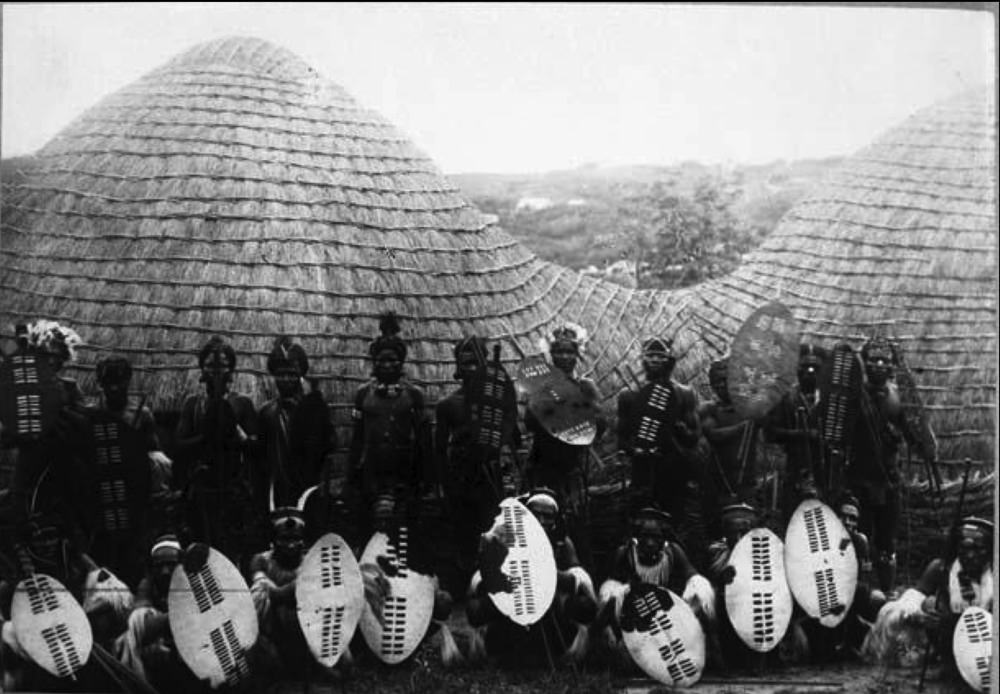

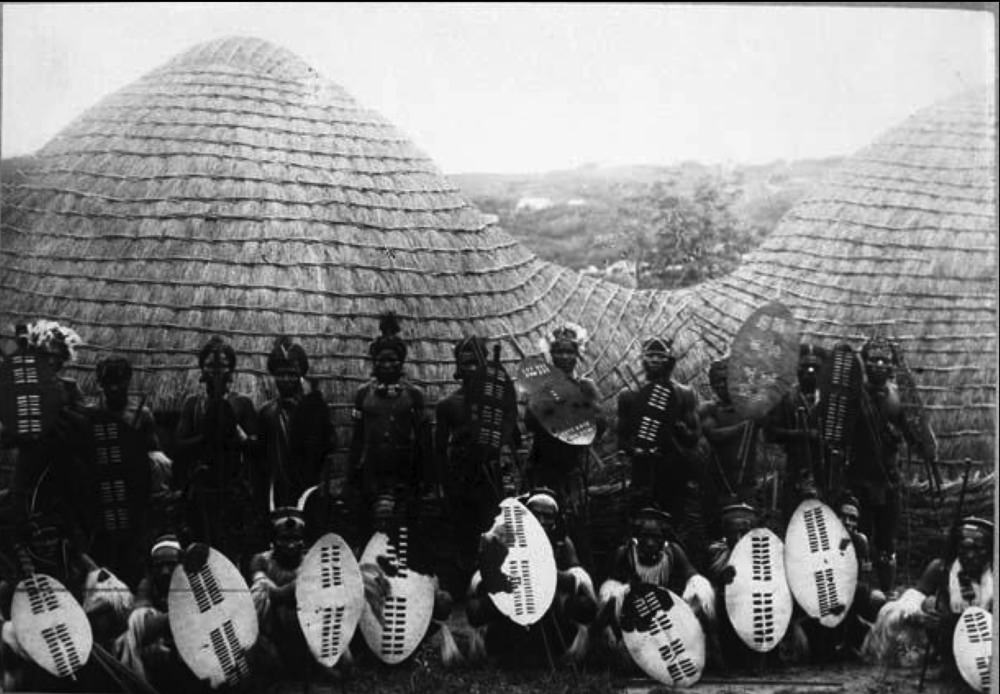

It is impossible to disconnect the sentimentalism of the nineteenth-century American women at her treadle from the larger political and economic processes that transformed and continue to transform our world. That insight invites an exploration of the collection of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology (Images 29-34).

(Click arrow at right to see images 29-34) Image 29

Courtesy of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University

Image 29

Courtesy of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University

Image 30

Courtesy of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University

Image 31

Courtesy of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University

Image 32

Courtesy of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University

Image 33

Courtesy of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University

Image 34

Courtesy of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University

Compare the highly exotic photograph from Zululand with the Singer trade card, which declares: “The native Zulus are a fine war-like people of the Bantu stock, speaking the Bantu language. This language extends over more than half of Africa and is one of great beauty and flexibility. The Zulu bids fair to be as forward in civilization as he has been in war. Our group represents the Zulus after less than a century of civilization. Worth wins everywhere.”

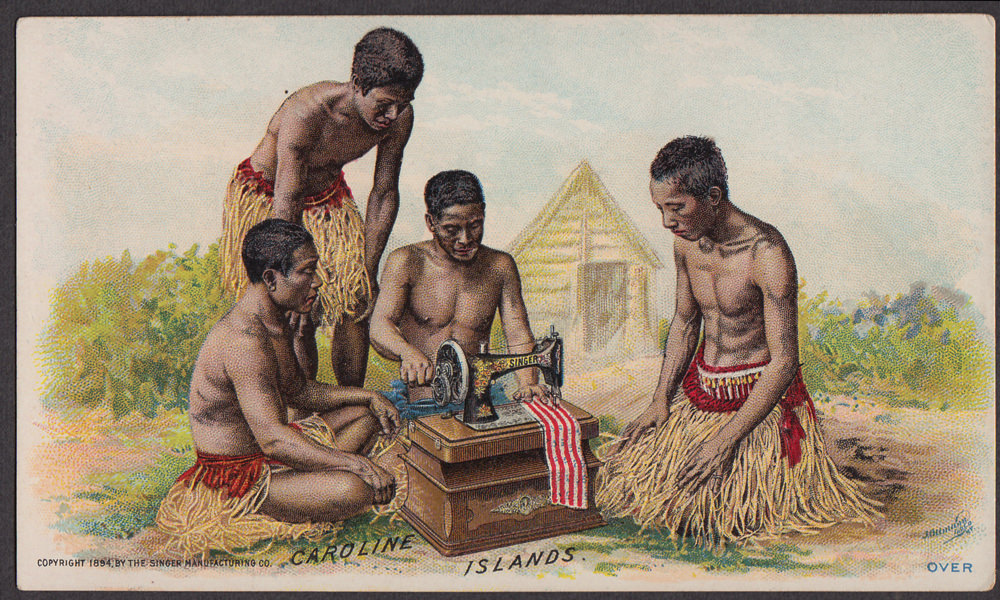

Even more intriguing is the card from the Pacific. Reporting on the Caroline Islands, the card states:

MISSIONARY WORK OF THE SINGER MANUFACTURING COMPANY. At the close of the recent war, the King of Ou (Caroline Islands) came to pay homage to the Government of Manila. As the best means of advancing and establishing a condition of things that would prevent all future outbreaks, the King was introduced to the “Great Civilizer,” the Singer sewing machine, and we have here his photograph, seated at the Singer sewing machine, with his Secretary of State standing beside him. This is absolutely authentic. It is a half-toned plate made from the original photograph, which can be seen any day at the office of the SINGER MANUFACTURING COMPANY, 149 Broadway, New York City.”

This trade card take on an entirely new meaning when we connect it with two items of clothing in the Peabody collections. One is a machine-sewn dress in European style made of Samoan tapa cloth. You can see the machine stitching clearly. The perhaps-local maker had been instructed by missionaries, in alliance with sewing-machine salesmen. These dresses were clearly made for exhibition rather than practical wear. Like the trade cards, they exemplied access to “civilization”—but at the same time replicating the theme of the Singer campaign: You can retain your cherished traditions, your unique national identities while participating in the products of global trade.

In preparing this text, I went back to Harvard search engines to see if I had missed an important collection in my explorations. I was surprised to discover a recent digital collection created by Afsaneh Najmabadi, Higginson professor of history and professor of studies of women, gender, and sexuality, in cooperation with Widener Library and the National Endowment for the Humanities.

(Click arrow at right to see images 35-38) Image 35: A sewing machine case…

Courtesy of Afsaneh Najmabadi/Widener Library and the National Endowment for the Humanities

Image 35 A sewing machine case…

Courtesy of Afsaneh Najmabadi/Widener Library and the National Endowment for the Humanities

Image 36 …and its contents

Courtesy of Afsaneh Najmabadi/Widener Library and the National Endowment for the Humanities

Image 37

Courtesy of Afsaneh Najmabadi/Widener Library and the National Endowment for the Humanities

Image 38

Courtesy of Afsaneh Najmabadi/Widener Library and the National Endowment for the Humanities

Image 39

Courtesy of Afsaneh Najmabadi/Widener Library and the National Endowment for the Humanities

On that website, which includes both oral histories and digital images of items in family collections, I found a lovely watercolor portraying an Iranian woman in “traditional dress" (Image 39) But I also found a surprising number of sewing machines, including those made by Singer and apparently shipped from the company’s factory in Russia (Images 35-38). One was given as part of woman’s dowry, another was passed on from mother to daughter, a third came with its own little table. I also found the fascinating story of Ebbi Haroutunion, an Armenian born in Russia who migrated to Iran with her family after the Russian Revolution of 1917, and eventually became employed by Singer to demonstrate its machines. She mastered the embroidery attachment and produced reproductions of European paintings with her machine, selling some and keeping a few for herself.

There is obviously a great deal more to learn about the distribution of sewing machines, but it seems obvious to me that they cannot fully be understood without the stories of those who used them and the artifacts they created. Seemingly indestructible, treadle sewing machines survive as a reminder of a powerful technology and an innovative marketing strategy now mostly forgotten. They show up on eBay, support table tops in pubs, ornament display windows in fancy clothing stores, and serve as anchors for small boats. But they can also connect aspects of history that far too often get separated in the way we think about, teach, and exhibit the past.

A couple of years ago, Ivan Gaskell, Sara Schechner, and I presented a program at which each of us argued that one of Harvard’s museums or libraries should accession my orphaned machine. Then we had the audience vote. The Peabody Museum won, but they weren’t interested. Today the sewing machine, beautifully restored to working order by Sara Schechner, resides in the office of professor of history Jane Kamensky, faculty director of the Schlesinger Library.