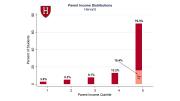

Harvard College has almost as many students from the nation’s top 0.1 percent highest-income families as from the bottom 20 percent. More than half of Harvard students come from the top 10 percent of the income distribution, and the vast majority—more than two-thirds—come from families in the top 20 percent.

These are some of the numbers revealed by a massive new data set and study of U.S. colleges, released this week. The study finds that Ivy League colleges remain largely inaccessible to low- and middle-income students, despite recruitment efforts and generous aid programs (like Harvard’s policy of awarding full financial aid to students from families earning less than $65,000). Among the most recent cohort for which data was available—corresponding approximately to the class of 2013—about 4.5 percent of Harvard students came from families from the bottom 20 percent of households. Only about one-fifth came from families in the bottom 60 percent. The median parental income for Harvard students was $168,800—more than three times the national median.

The study, conducted by economists Raj Chetty, John Friedman, Emmanuel Saez, Nicholas Turner, and Danny Yagan, used tax filings to follow more than 30 million college students born between 1980 and 1991, tracking both their parents’ earnings and their own postgraduate earnings. Each college was given a mobility score, based on the proportion of students who begin in the bottom 20 percent of households, measured by income, and end up in the top 20 percent.

At top colleges overall, the proportion of students from the richest 1 percent of families has increased during the last decade, while the proportion from the bottom 40 percent has decreased—a significant finding that had previously been obscured by the increased number of students at Ivy League schools receiving Pell Grants. The authors report two reasons: the federal government significantly increased the income eligibility cutoff for the grant, which is awarded to students from low- and middle-income families, during the study period. In addition, the real incomes of low-income families fell significantly during the same period, when income inequality grew rapidly nationwide. But, the authors add, the data “do not imply that the financial aid expansions and other efforts from elite private schools to expand access for low-income students were ineffective—indeed, it is possible that access at Ivy-plus colleges would have fallen were it not for these policies. It is clear, however, that economic diversity did not expand as much as Pell shares suggest during our sample period.”

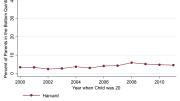

Harvard represents somewhat of a departure from that trend: its 4.5 percent of students from the bottom 20 percent of the income distribution is up from 3.3 percent a little more than a decade ago. The number of enrolled students from the bottom 60 percent increased from 16.1 percent of undergraduates during the first half of the data set to 20.9 percent in the second, coinciding with significant expansion of the College’s financial-aid program. “Harvard was one of the most aggressive elite schools in pushing to expand access during our sample period,” the study notes, “and it resulted in a broad pattern of increasing access.”

Still, the median college in the nation drew 9.3 percent of its students from the bottom 20 percent during the study period—more than twice the proportion at Harvard and its peer schools. The schools with the highest mobility scores included less selective public colleges and universities that enroll and graduate large numbers of poor students, like the City University of New York (CUNY) and the California State system. These schools, writes David Leonhardt in The New York Times, “remain deeply impressive institutions that continue to push many Americans into the middle class and beyond—many more, in fact, than elite colleges that receive far more attention.”

Another notable finding: poor students at top colleges do virtually as well as their higher-income peers after graduation, at least in terms of how much money they earn—a rebuttal to the popular “mismatch” theory. The authors openly discredit it: “there is little mismatch of low socioeconomic status students to selective colleges.” Low-income students at the most elite universities also out-earn their peers at schools with high mobility scores.

Relying on students’ earnings alone can’t account for the other challenges—cultural, academic, and others—that low-income students experience in college. Nor can it account for the type of work that they go into—it’s little secret that graduates of Harvard and peer universities earn high salaries at a young age, in part, at jobs on Wall Street and in consulting, the same institutions that have shared blame for worsening income inequality. But the findings do suggest that elite universities are major engines of economic mobility, and they could do more if they enrolled more low-income students. “Our data and the work of other researchers also suggest that there still are many low-income students out there who, if given the opportunity, can succeed at highly selective colleges,” author John Friedman ’02, Ph.D. ’07, associate economics professor at Brown, wrote in an email. He also noted that “the literature more broadly suggests that interventions that reach students before they begin applying to college, such as targeted outreach and mentoring programs in elementary, middle, and high school, may be particularly valuable at increasing the number of high-achieving, low-socioeconomic status students that apply and ultimately attend schools like Harvard. Elite private schools may also be able to learn from the experiences of public schools like CUNY in attracting and serving low-income students, for instance through community college transfer programs.”

Asked for comment on the data, the College provided Harvard Magazine with a statement of its current financial aid policy from dean of admissions and financial aid William Fitzsimmons: “We are fundamentally committed to access for all students and meeting the full demonstrated financial need of every student admitted through our need-blind admissions process. Families with annual incomes of $65,000 or less do not pay anything toward the cost of their child’s Harvard education. And one in five undergraduates is from a family with annual income of $65,000 or less. The majority of undergraduates receiving financial aid pay just 10% of annual family income, and this standard holds for families earning up to $150,000/year. Harvard awards grants only and never requires students to take out loans to cover the cost of their education.”

Harvard’s progress in recruiting more talented low-income students, however modest, suggests significant gains are within reach, given the right institutional resources and resolve. Writes Friedman, “Because of Harvard’s unique role as a leader in higher education, further improvement can not only affect Harvard’s own students but also push other institutions in the right direction.”