On July 11, Corporation senior fellow William F. Lee wrote to the Harvard community, soliciting advice about the qualities the University’s new president should have. The same day, the Pew Research Center reported unsurprising, but dismaying, news: reversing earlier polls, a majority of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents now think colleges and universities damage the country. Weeks later, a Democratic political-action committee released polling research that found that a majority of white working-class voters believed a college degree ensured more debt but little likelihood of securing a good job; 83 percent concluded that a college degree no longer guaranteed success. Such findings seem to spell disaster for the prospect of Americans agreeing on an agenda to advance knowledge and equip citizens with what they need to succeed.

What does this have to do with the search for Harvard’s twenty-ninth president? At a minimum, it suggests that she or he should be talented at communicating the institution’s role in society—and eager to do so beyond the Crimson community. It also raises questions about who gains admission in a hyper-competitive era, and points to the need to air that out more fully.

Those demands—and the many others any president will face—underscore the urgency of articulating a more sharply defined, credible narrative about the institution that reflects a rigorous strategy. Charles William Eliot declared in his inaugural address, in 1869:

This university recognizes no real antagonism between literature and science, and consents to no such narrow alternatives as mathematics or classics, science or metaphysics. We would have them all, and at their best.

Harvard leaders have understandably embraced his robust formulation. It is comforting to associate with greatness, and “best” has a nice ring to it: aspirational, good for fundraising. And that limitless “all” eliminates the burden of choosing.

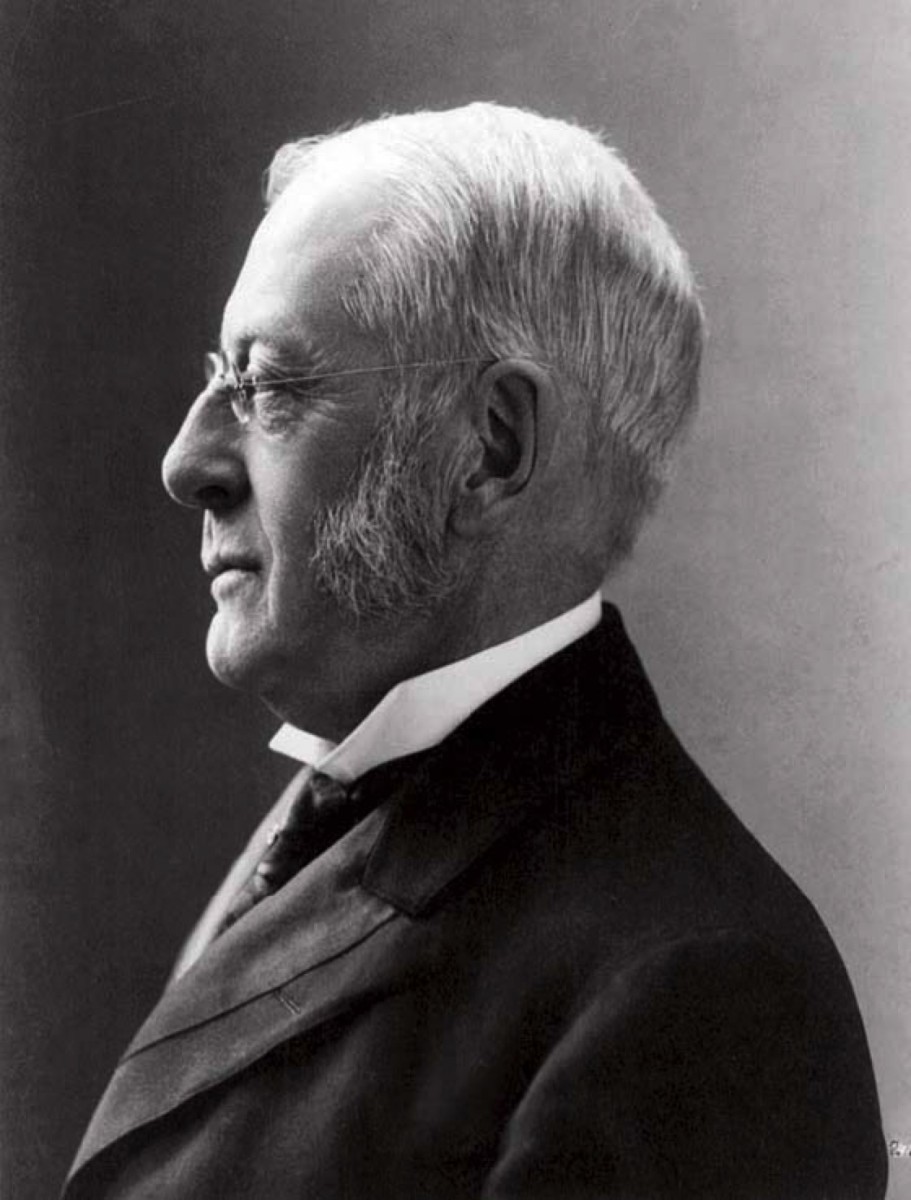

Eliot: Having it all

But perhaps Harvard has lingered in the shadow of having it all and at its best too long. In the past decade, as an implicit strategy, the University has invested heavily in engineering and applied sciences. But even as those fields draw more students, the faculty remains far smaller than Princeton’s (not to mention MIT’s)—and scaling up further will take additional billions, amid the competing needs of other pricey priorities like life sciences. Should Harvard partner with MIT in a regional engineering and applied-sciences cluster? As the neurobiologist now at Stanford’s helm aims at a Bay Area life-sciences cluster (perhaps embracing UCSF, Berkeley, large local biotechnology enterprises, and the many area data scientists), can Harvard, with Boston’s natural advantages, build unquestioned leadership in that field—and again, at what cost? Meanwhile, the University is tiptoeing into more curricular art-making—but trails Yale, while Princeton and Stanford have recently created campus arts precincts.

Suggesting that Harvard or any institution has it “all” today, and “at their best,” is an invitation to complacency or self-delusion. No one has enough money to fulfill that aspiration, or the facilities to accommodate everyone who would have to be involved. Insisting on it will only confuse constituents at hand (faculty members, students, administrators); those emotionally nearby (alumni, philanthropists); and those farther afield (the rest of the country and world, including political leaders).

In his useful and accessible recent book, Realizing the Distinctive University: Vision and Values, Strategy and Culture (Notre Dame Press), Mark William Roche, a scholar of German and of philosophy, and former dean of Notre Dame’s College of Arts and Letters, writes,

[O]ne of the great dimensions of the American university landscape is its diversity. Ohio State has a different vision of itself than does Williams College. Notre Dame is different yet again. Each university benefits from being able to articulate in meaningful and not simply incidental ways why a particular student or faculty member should be drawn to that institution.

Roche adds that such a vision is also “the best brake on the homogenizing tendencies of rankings. It offers students, faculty, and others additional opportunities for intrinsic motivation and emotional identification”—invaluable, even if not toted up on a balance sheet. Conceiving and animating a vision does “require tremendous effort in terms of faculty socialization, support structures, communication, incentives, and leadership,” he notes. But given the complexities of running universities in an era of rising costs and doubts about their societal value, any institution and its leader are clearly better off defining such a vision than simply winging it.

Eliot would be proud that his ambitions still resonate as the University he transformed nears its four-hundredth anniversary. To do him credit, and make that celebration a great one, bringing the community together to articulate a vision and refine a strategy tops any Harvard leader’s agenda.

~John S. Rosenberg, Editor