“Magic” is what Jack Lueders-Booth calls it: In careful darkness, a photographer immerses paper in a chemical brew and agitates until shadows blossom. But if that process is a kind of alchemy, then instant film is sorcery, trapping a moment behind a pane of plastic—10 discrete layers of chemicals in a precise chain of reactions. The resulting image cannot be reproduced, and proves challenging to preserve.

But when Lueders-Booth, Ed.M. ’78, uncovered a set of four-by-five-inch Polaroid photographs he had taken 40 years ago, they were improbably intact. Today, the images still pulse with deep-water blues and heart-blood reds. The young women depicted meet the camera’s gaze unflinchingly, emissaries from their time, a group portrait of easy confidence. On display at the Aperture Foundation gallery in New York and Gallery Kayafas in Boston this spring, only the wall text gave them away: “Women Prisoners.” Lueders-Booth initially went to MCI-Framingham, a Massachusetts state women’s prison, as a teacher. But from 1978 to 1985, what began as a gesture of service became a passion project involving dozens of instant and other cameras and hundreds of sheets and rolls of film—the students,’ and his own.

His scientist father had been an amateur photographer, but an “intimidating” one, who mixed his own darkroom solutions from powdered chemicals. Lueders-Booth was 35* before he jumped in with both feet, hungry for creative expression and hooked on the process and gear. In 1970, he left his job as an office manager at an insurance company—despite three dependent children and the security of a career track—to pursue photography.

The Boston photography scene included staff of the nascent Harvard photography program, who invited him to manage it and teach a few classes. Eventually, Lueders-Booth enrolled at the Graduate School of Education, in need of a piece of paper to confirm what the department already knew about his pedagogy. (In his 30 years of teaching at Harvard, he has earned 12 commendations for distinguished teaching, and been nominated three times for a University-wide teaching prize.)

He’d been bringing photography to people confined to institutions, volunteer teachingat a chronic-disease hospital in Boston Harbor, when, for his master’s thesis he proposed continuing the work at MCI-Framingham, the oldest women’s prison in the country. (It was founded in the 1850s to punish women guilty of “begetting”: bearing children out of wedlock.) Prison administrators gave him the run of an empty wing for a dark room, and Polaroid provided a dozen cutting-edge cameras as well, plus as much film as the class could use. Lueders-Booth built out the space, fitting sinks and installing donated enlargers; he brought along his 18-year-old daughter, Laura, as an assistant. Progressing from camera obscuras to photograms to paired portraits, each exercise proved more entrancing to the prisoners than the last.

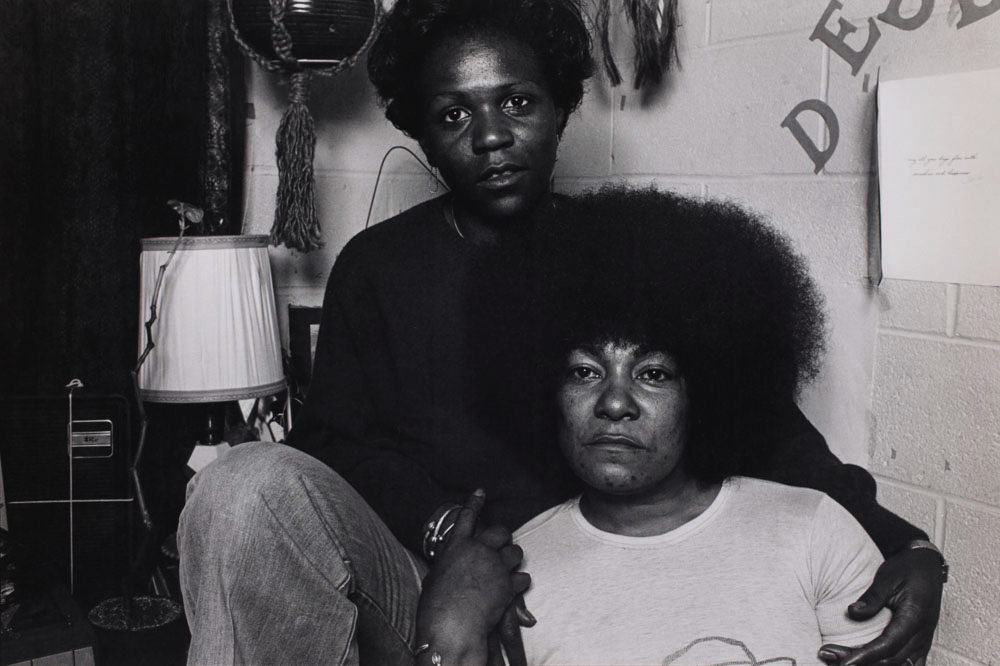

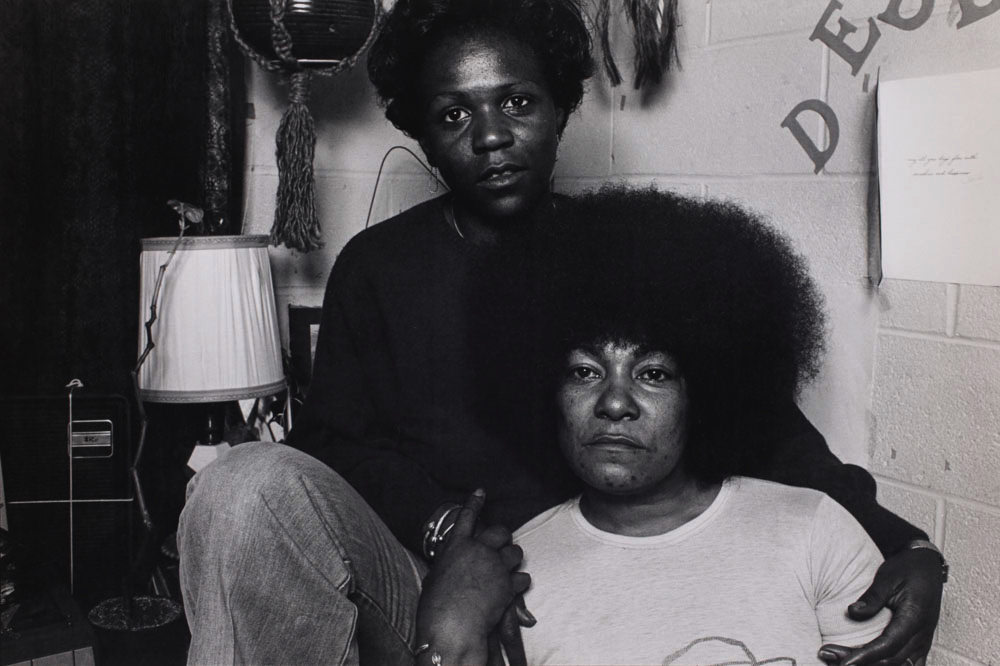

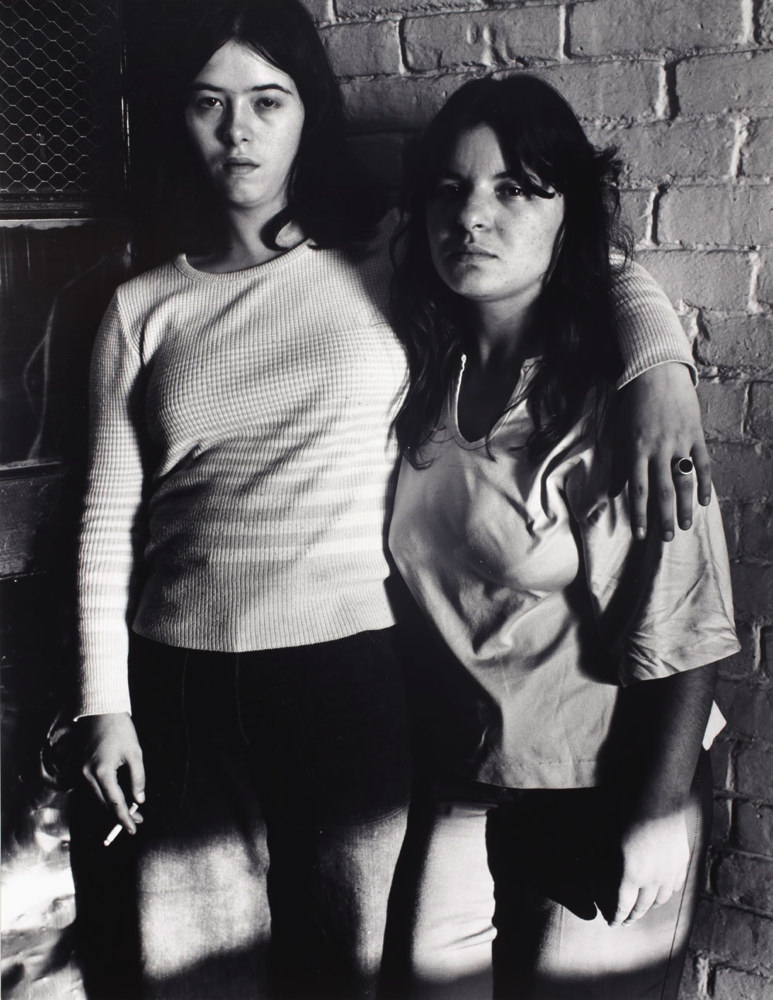

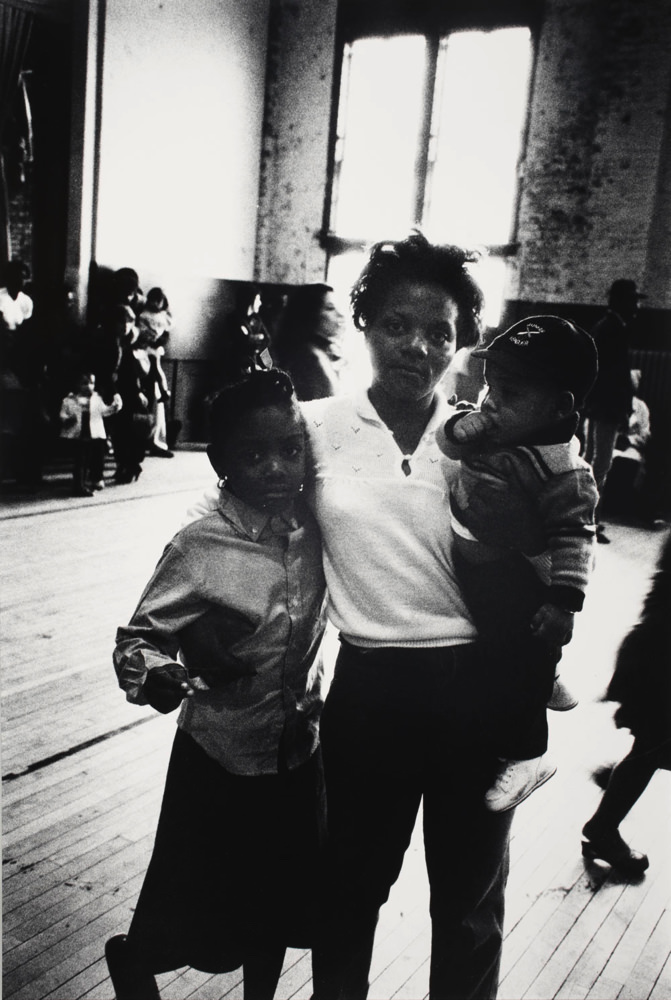

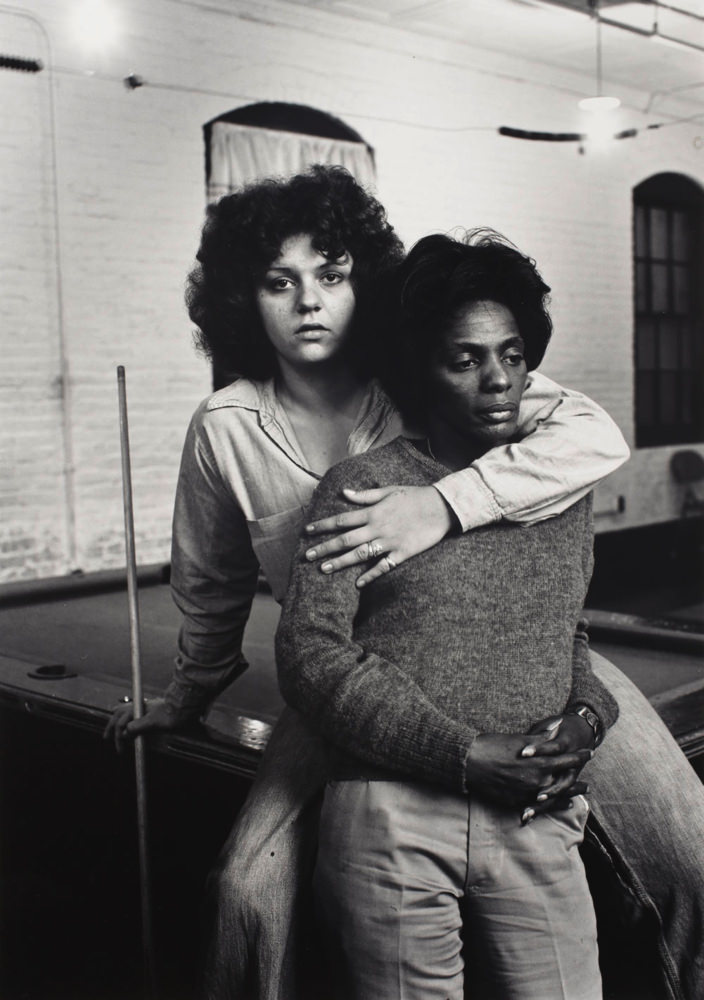

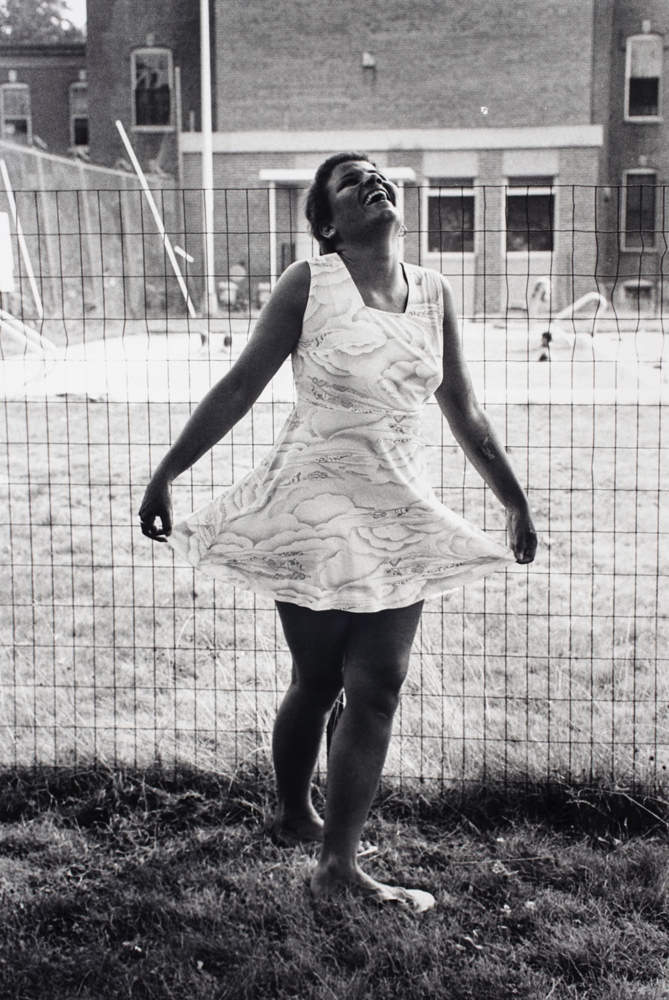

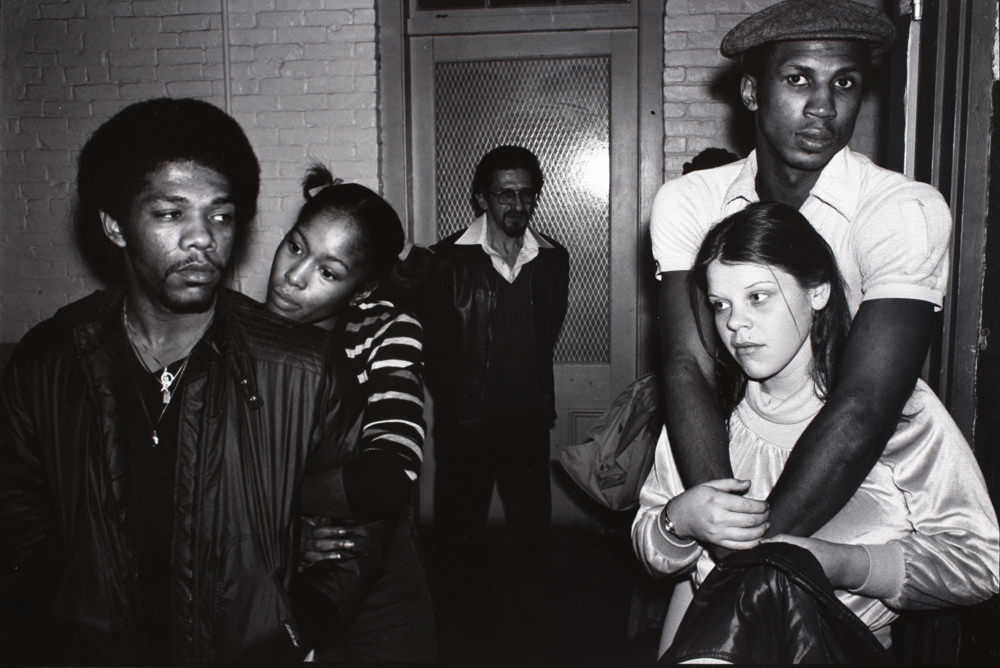

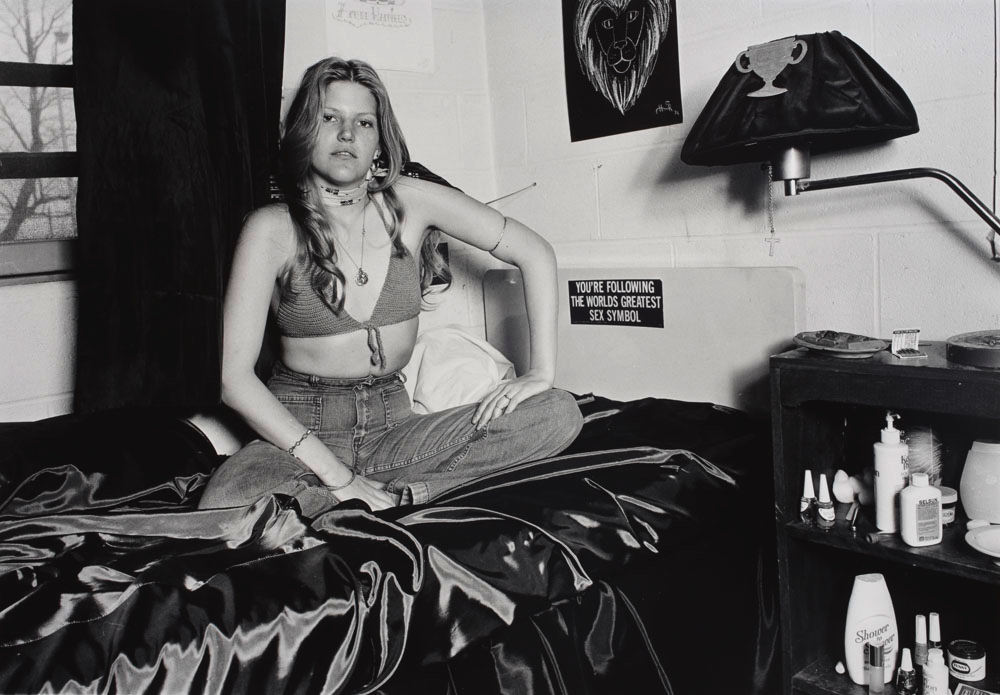

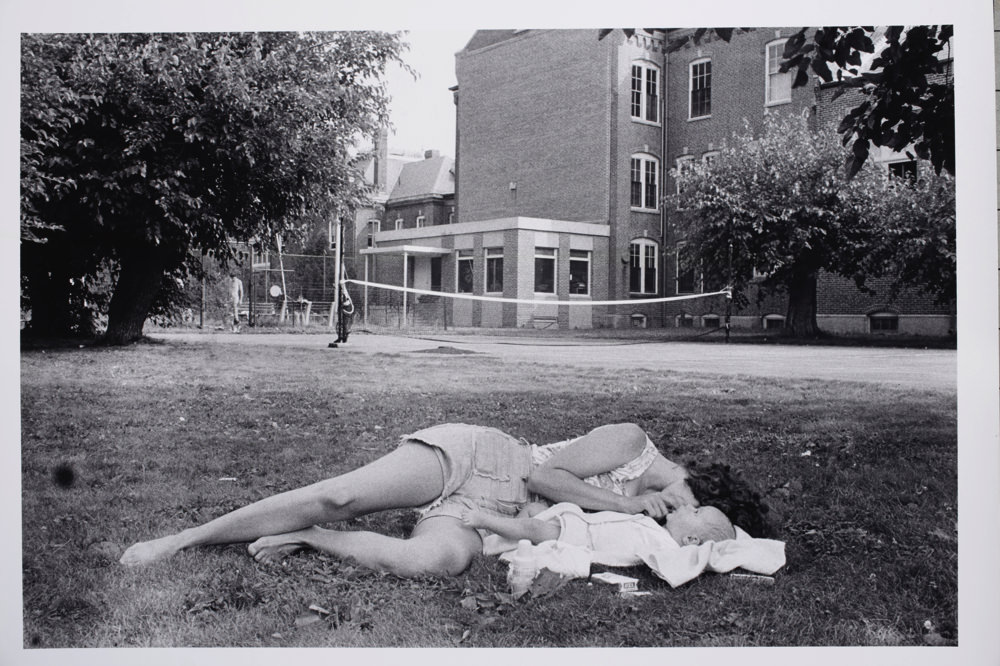

Photograph courtesy of Jack Lueders-Booth/Gallery Kayafas

Photograph courtesy of Jack Lueders-Booth/Gallery Kayafas

Photograph courtesy of Jack Lueders-Booth/Gallery Kayafas

Photograph courtesy of Jack Lueders-Booth/Gallery Kayafas

Photograph courtesy of Jack Lueders-Booth/Gallery Kayafas

Photograph courtesy of Jack Lueders-Booth/Gallery Kayafas

Photograph courtesy of Jack Lueders-Booth/Gallery Kayafas

Photograph courtesy of Jack Lueders-Booth/Gallery Kayafas

Photograph courtesy of Jack Lueders-Booth/Gallery Kayafas

Photograph courtesy of Jack Lueders-Booth/Gallery Kayafas

Meanwhile, Booth roamed the grounds with his 35-millimeter Leica, becoming, he says, “sort of the school photographer of MCI-Framingham,” or like the prisoners’ uncle: a familiar but slightly removed presence. Though he had preconceptions about the people he would meet there (and had sworn off documentary photography) he was soon “smitten” by his project, and became involved in his students’ lives. In one of his favorite shots, a prisoner who served as a teaching assistant is photographed with her father, who visited her every day on his way home from work. Lueders-Booth is equally taken with the photo’s composition—the curve of their entwined arms, the rhyming tilt of their faces—and the obvious devotion on display.

In the Aperture Foundation gallery’s “Prison Nation” exhibition, much of the other prison photography made for bleak documentation of a dehumanizing process. But there are no striped jumpsuits in Lueders-Booth’s pictures; the women wear their own clothing, and their cells are decorated with photographs, drawings, greeting cards, crocheted blankets, figurines, radios. Windows are covered with gauzy curtains, and window bars, when visible, are horizontal and sheathed in aluminum to imitate Venetian blinds. “They really look more like UMass dorm rooms than prison cells,” Lueders-Booth says now.

He credits the prison’s softer touch to then-governor Michael Dukakis, LL.B. ’60 (who was attacked for his humane approach during the 1988 presidential election). One photograph depicts the graduation ceremony from a high-school equivalency program. Though far from picturesque—one graduate smokes, another leans on crutches, another picks her nose—there is a sense of possibility. One young woman lounges on a blanket on the grass, her face hidden behind the baby she cradles. A tennis court is visible in the background.

Lueders-Booth’s freedom to photograph was also a product of the time. “I had too much access, really,” he says. “But I took the responsibility of that to heart.” He witnessed it all. One young woman, another teaching assistant, extends her forearms toward the camera, showing raised scars marking her struggles with bipolar disorder; others wear their hard lives on their faces. Lueders-Booth recalls how some women returned to prison mere months after being released, looking ill-fed and roughed-up by their time on the streets, and oddly the better for being back at MCI-Framingham.

This unlikely access could not last. At first, Lueders-Booth hadn’t intended to share the photographs with the outside world, but when hints of interest from publishers inspired panic among administrators, he left the prison behind, and lost all contact with the women he had photographed. In the 1980s, hoping to discuss publication of his images (and the resulting royalties for the women), he wound up walking the streets of Boston after dark, appealing to sex workers, drug users, and homeless people for help. Tracking his subjects through the night, with a stack of photos for identification, was like chasing ghosts.

Eventually, Lueders-Booth and his camera moved on to vastly different environs, ranging from postindustrial New England cities to Central American garbage dumps. But outside interest in the worlds of prisoners has only intensified recently. As greater knowledge of “mass incarceration” reaches the mainstream, artists, writers, and curators alike are documenting the generations lost to an unjust system. Yet his photographs are a category apart. Many other photographers mobilize images of incarcerated people—mostly men, mainly black, in jumpsuits and uniforms, toiling on prison farms or enclosed by heavy walls—to illustrate the system’s crushing weight. Lueders-Booth’s portraits catch unlikely personal moments, protecting vulnerability and individuality as if behind a pane of glass.