Collectors have long been smitten with artists’ better-than-photographic renderings of charismatic fauna (Audubon’s birds, for instance) and flora. Among them, happily, was Mildred Bliss, who with her husband, Robert, A.B. 1900, created what is now Harvard’s Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, and its splendid gardens, in Washington, D.C. Among her purchases are 21 botanicals painted by Margaret (Brown) Mee (1909-1988) during the first three of her remarkable 15 expeditions to Amazonia, from 1956 through the year of her death.

The English-born Mee studied at various art schools before she and her husband, Greville Mee, first visited Brazil in 1952 to help her ailing sister; while there, she began painting local species. Back in Brazil in 1956, she consulted local experts, and began working seriously. A 1958 exhibition of her art at the São Paolo Botanic Institute, where she deepened her research on tropical plants and met leading botanists, underpinned the expeditions that followed, focused on bromeliads (including discoveries named after her) and other passions. Flowers of the Brazilian Forests and Flowers of the Amazon made her work, increasingly driven by concern about rainforest destruction, accessible to a wider public.

But nothing compares to experiencing Mee’s gouaches (watercolor made less transparent through the addition of white pigment and a binder). The Dumbarton Oaks holdings, presented there together for the first time (doaks.org/resources/online-exhibits/margaret-mee-portraits-of-plants), show the results she obtained by working from live, individual specimens. Tabebuia umbellata (Sond.) Sandwith, the deciduous yellow trumpet tree (shown above), fairly glows against its ground paper—complemented by details of the reproductive structures, and Mee’s impeccably lettered identification, dating, and signature.

Such veracity did not come cheap. Mee, often accompanied only by local guides, contracted severe cases of malaria and hepatitis. Her fortitude came, apparently, from within: traveling to Germany in the early 1930s, she witnessed the rise of Nazism and the Reichstag fire; her first husband was a union activist; she had advocated for the jobless and opposed fascism in Spain.

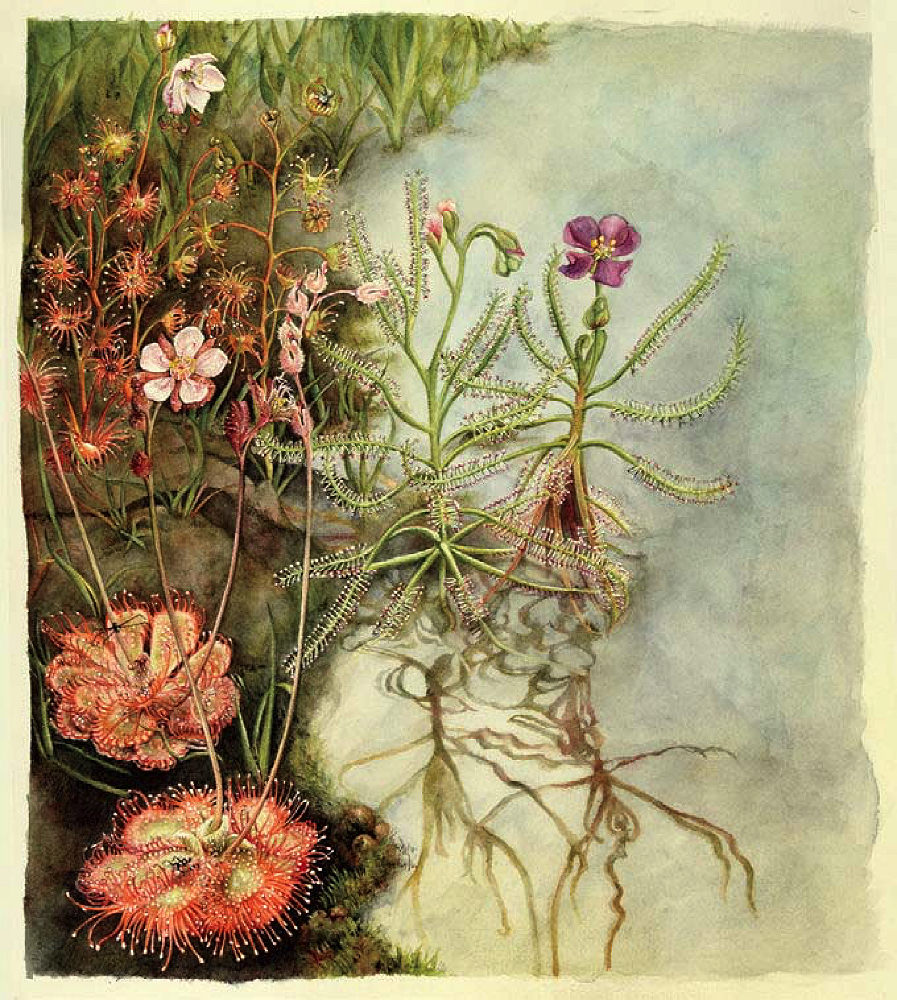

Painting by Nirupa Rao

The exhibit organizers (executive director Yota Batsaki, curator of rare books Anatole Tchikine, and postgraduate curatorial fellow Leib Celnik) have placed Mee’s paintings in the contexts of botanical art through the ages and of contemporary women active in the field: photographer Amy Lamb, Smithsonian illustrator Alice Tangerini, and artist Nirupa Rao, also an intrepid rainforest visitor, represented by carnivorous sundews (shown above). Rao could not be more stylistically different from Mee, but the clarifying virtues of her eye and hand are readily apparent.

Sadly, the horrific deforestation since Mee raised her alarm gives some of her work historical, as well as aesthetic and scientific, importance. The exhibition thus demonstrates an enduring service to Amazonia, by an Amazon among botanical artists.