A new interchange was coming to Cincinnati, and it was about time. The I-71 thoroughfare had connected the city to its suburbs since the 1970s, but its lanes also separated neighborhoods and worsened travel within the city—lengthening commutes and emergency trips to nearby hospitals. An $80-million project would change that, adding a traffic interchange linking communities long disconnected. It would be “a catalyst for future economic development and thousands of new jobs in Uptown’s seven Cincinnati neighborhoods,” its designer concluded.

But who would benefit from that economic development? Stephen Gray, M.Arch.U ’08, couldn’t help but wonder. An urban designer at Sasaki Associates, he had grown up in Cincinnati, attended college there, and written both his undergraduate and graduate theses on new projects in the area. When his firm was chosen in 2013 to help prepare Uptown Cincinnati for the new interchange, Gray was the natural choice to manage the job.

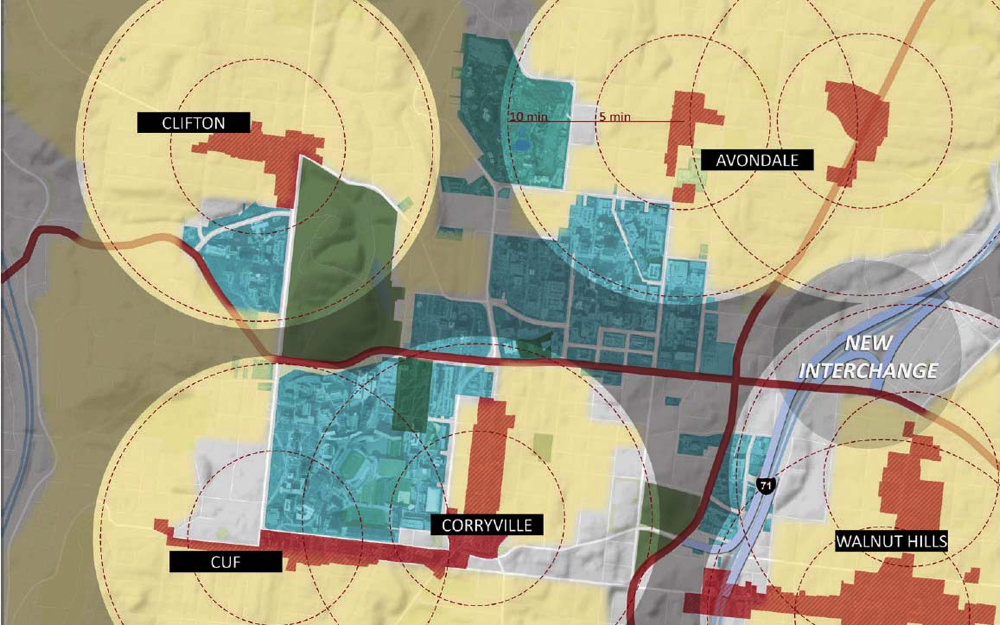

His priority wasn’t to create one stunning building or envision a unique aesthetic for a complex that lovers of architecture would admire. He was there to ensure that the “Innovation Corridor,” a mixed-use development designed to take advantage of the new interchange, made sense for all stakeholders. And there was no shortage of interested parties. The Uptown area is the city’s second-largest job center and home to some of its biggest institutions—the University of Cincinnati, the Cincinnati Zoo, and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center—all urging the project’s completion. It also includes neighborhoods like Avondale, a center of civil-rights activism in the 1960s that is 92 percent black, and 40 percent of whose residents live at or below the poverty line.

And despite the presence of powerful local institutions, the area was known for limited public open space, poor pedestrian connectivity, and scant options for affordable housing and public transportation. Even if the new project addressed some of these issues, residents of Avondale openly wondered if they were going to be gentrified out of their long-time homes—something they saw happening in other predominantly black Cincinnati neighborhoods. The project was coming, and Gray wanted to make sure those residents weren’t pushed aside as others reaped financial rewards.

He had an idea for ensuring a fairer outcome. Five years earlier, he had written his graduate thesis on how to create a process—before a project’s funding was decided—to make sure all stakeholders’ needs were met. Now, he had an opportunity to test his thesis in real life by creating a “cross-sectoral interest group” that worked together in his home city.

To begin, Gray and his colleagues drafted a second economic analysis. The original one, arguing for the interchange, had discussed the project’s benefits in general terms: it would create a tax windfall for the city and improve access to the area’s principal attractions. The new one revealed some problems. Of the million square feet of commercial space Uptown would gain, a couple hundred thousand would likely go unused; there weren’t enough residents to support the businesses. Furthermore, the project’s backers were promoting the positive impacts of a new interchange and development that would add more car traffic to an area already roughly equal parts residential land and surface parking—even though most residents didn’t have cars.

Adding community leaders to the steering committee hadn’t allayed concerns. “The neighborhood executives didn’t trust the process at all,” Gray says. “They didn’t trust the institutions. They were just showing up to make sure they didn’t get bulldozed. Or, if they were going to get bulldozed, so they could see it coming.” In early one-on-one meetings Gray and his colleagues had with those leaders, almost every one said their neighborhoods saw the institutions pushing the project as destructive forces. “A common narrative began to emerge,” he says. “There was little to no investment in the mostly black neighborhoods by major institutions.”

When he and his team presented their findings at a public listening session, they were blunt. “We said, basically, ‘We’ve talked to everybody and there seems to be a lot of consensus around the fact that you guys have failed your commitment and that nobody trusts you,’” Gray emphasizes. As the audience listened, he noticed community-organization leaders on the steering committee perk up. This was not the way they were used to hearing consultants talk to their clients, much less publicly. “It made people realize,” he says, that involving the neighborhood “was going to be a genuine process.”

Once the new research had been presented, negotiations began. Gray broke attendees into two groups, splitting institutional representatives, city officials, business owners, community-development corporations, and community-based organizations evenly between them. Then both groups got a printout of the Innovation Corridor plan and play pieces—representing commercial, residential, and institutional research space, open space, and street trees—and had to decide how to allocate its pieces on the map. By meeting’s end, the groups presented similar ideas.

“It allowed us to come up with a synthetic plan that everyone could look at and understand how that related to them and their focus,” Gray explains. Institutions saw how the new corridor would concentrate commercial and research development along the area’s spine and crossroads down the street from the interchange. The neighborhoods got an acknowledgment that the area should be increasing its residential base, not demolishing it.

And the outcomes complemented each other. A growing population meant more business for the new commercial spaces. A developed area with improved crosswalks and green space made the area more attractive for institutions and residents alike. “By the end of the project, not only did we have consensus,” Gray reports, “but also all of the community-based organizations wrote letters of support to the Cincinnati Planning Commission.” The process had paid off.

Yet the typical design process isn’t so collaborative, says Gray, now associate professor of urban design at the Graduate School of Design (GSD). Instead, he explains, in many cases private developers bring money to the table and say how they want to spend it. “The public sector says, ‘That’s great! Let us know how we can help—but make sure you share this with the neighborhoods or we’re going to get some major blowback.’” Facing the inevitable, the affected residents often settle for a minor benefit: a playground, space for a community center, upgrades to the immediately surrounding area. Sometimes city officials combine several projects into a larger, cohesive plan that may make more sense for constituents. These plans can work fairly well, Gray says, but often resemble failed urban projects from the 1950s through the 1980s, when cities across the country cleared neighborhoods for private development and ended up with underdeveloped areas and decimated communities. Rarely do such processes engage meaningfully with all stakeholders.

“Equity is where people aren’t asked whether this bench is red or blue, but rather, is this project right or wrong?”

But it’s not easy to bring about better outcomes. Governments need to get projects built, but often don’t have the money to pay for major public infrastructure investments. “The private sector already has quite a bit of power,” Gray says, “but that gives them even more power, because now they basically know that the government needs them in order to leverage and get public good.” Residents of the surrounding communities generally are engaged only late in the process: informed of how things are going to work and how they may expect to benefit only after most of the plans have been solidified. Gray doesn’t think that’s fair. “Equity,” he says, “is where people aren’t asked whether this bench is red or blue, but rather, is this project right or wrong?”

His awareness of different communities, and equity, started young. Growing up as the child of a white mother and black father, Gray never quite fit into any one group. Visits with his mother’s relatives took him to the hills of rural Kentucky, where houses were separated by half a mile and every other one had a Confederate flag. Every year, Gray and his family watched his grandmother’s sister perform with her family’s traveling bluegrass band and enjoyed a pig roast and jamboree. “We were the little black kids who were VIP in the house,” Gray says, “and no one could really understand why.”

His father’s mother had grown up in Alabama, attending elementary school with Coretta Scott King. She told stories about how when temperatures dropped, her family would let their cows gather under their house so they could keep warm.

Being exposed to the different experiences was formative. “Your aunties tell you exactly what they think,” Gray says. “You’re sitting around, they just made some food…and they start talking about stuff that’s on their mind. And they’re always straightforward. You get a little glimpse into how people think about themselves and about each other.”

Gray never felt out of place in school, but he never felt in place either. One of the few multiracial kids with experiences that didn’t line up with anyone else’s, he never knew quite where to sit during lunch, so he just rotated from table to table. His race wasn’t the only thing that made him unique. “We were mixed, we were vegetarians, we had been to India twice, we were somewhat-practicing Hindus,” Gray rattles off. “All of that was weird, right? Especially back in the eighties.”

His parents had eclectic interests. His mother was a sculptor and art teacher, and his father taught high-school math, practiced Korean martial arts, wrote poetry in Old French, and practiced 12-string classical guitar and Irish fiddle. By the time Gray was five or six, his father had bought him a compass and begun teaching him geometry. Family friends thought Gray should follow in the footsteps of his parents. “At some point, someone said, ‘Oh, your father’s a mathematician, your mother’s an artist, you should be an architect!’” Gray recalls. “So then all growing up, I would say, ‘My mother is an artist, my father is a mathematician, so I’m going to be an architect!’”

When choosing his college major at the University of Cincinnati, he realized that he didn’t actually know much about architecture, but it seemed a good enough fit. He took two architecture internships before a mentor recommended that he get some hands-on construction experience. Gray made that more personally interesting by working for Habitat for Humanity in Costa Rica for six months, building houses by hand and learning Spanish by necessity, through dating. By the end, he’d built three homes, each worth $7,000, working alongside the people who were going to live in them. But it didn’t seem to him that he’d done enough. “Working with Habitat made me see how much needs to be done in the world,” Gray says, “and that generally architecture doesn’t serve any of those purposes.” What it mostly did, he thought, was “deliver fancy things to fancy people who have a lot of fancy things.”

After returning from the trip, he turned to urban design. Situated between architecture and urban planning, the field allowed him to merge the design and spatial attributes of architecture with the policy perspectives of urban planning. It was also a field in which he could put his strongest skill into his work: relating to many different kinds of people and gently, but firmly, pushing them toward productive collaborations. “He’s just one of those rare people who is able to have very strongly held opinions and approaches to things without delivering them in a way which is oppositional or confrontational,” says architect Richard Sommer, director of the Global Cities Institute at the University of Toronto, who co-advised Gray’s graduate thesis at Harvard. “I think this is why the role of being a mediator…is one I think he’s extremely well suited for.” After graduating from Cincinnati in 2003, he began a graduate degree in urban design at Harvard.

Though he had spent much of his life avoiding reading (which often prompted severe migraines), he read as much as he possibly could in graduate school. “I would put money on me being the person who read the most assigned reading of anyone in my class,” Gray says, joking. “And I only read three-quarters, because it’s just impossible.” He was especially taken by “Histories and Theories of Urban Interventions,” a course taught by Margaret Crawford (now at the University of California, Berkeley) that surveyed efforts to alleviate poverty and overcrowding in different cities. Hampered by redlining and exclusionary suburban expansion, many of the projects failed.

Eventually he decided to write a thesis, a project rarely undertaken by students in his program. (Not wanting to be the only one doing so, he convinced friends to do their own.) Gray focused on a streetcar project in downtown Cincinnati that had been approved after multiple ballot efforts, and asked then-professor of urban planning Susan Fainstein, a political theorist and influential voice for racial equity in urban planning, to co-advise the project with Sommer. He wanted to figure how to develop an “urban growth regime,” including multiple groups—rich and poor, public and private—to make sure such public investment benefited not just businesses, but also the communities with the most at stake after the project’s completion. He also suggested revisions to the existing proposal, which linked Findlay Market, a predominantly poor, black area, to the affluent Waterfront area along the Ohio River. “Nobody from either of those sides is ever going to go to the other side,” he argued. He suggested that the city extend the line to the University of Cincinnati, instead, giving students an opportunity to check out all the connected neighborhoods.

To Gray’s disappointment, the city didn’t extend the line initially, but it is considering doing so in the future. Five years later, the Innovation Corridor project appeared. It would give him the confidence to continue pursuing his collaborative process.

Many firms aim to establish a signature look and stylistic approach in all their projects, Gray acknowledges. But at his own firm, Grayscale Collaborative, he wants to establish a signature process—one that incorporates community leaders and residents into discussions long before they’re typically allowed in, and one that puts race at the center of the conversation. “If we’re too focused on the product and outcome and the image of what we’re doing,” and the process of actually doing it is less important, Gray says, “then we’re going to fail society.” Projects, he adds, can be economically and politically successful without such collaboration—and at times socially successfully as well. But often, he finds, firms know their work is going to have an effect on the community, but don’t think about what that effect will be.

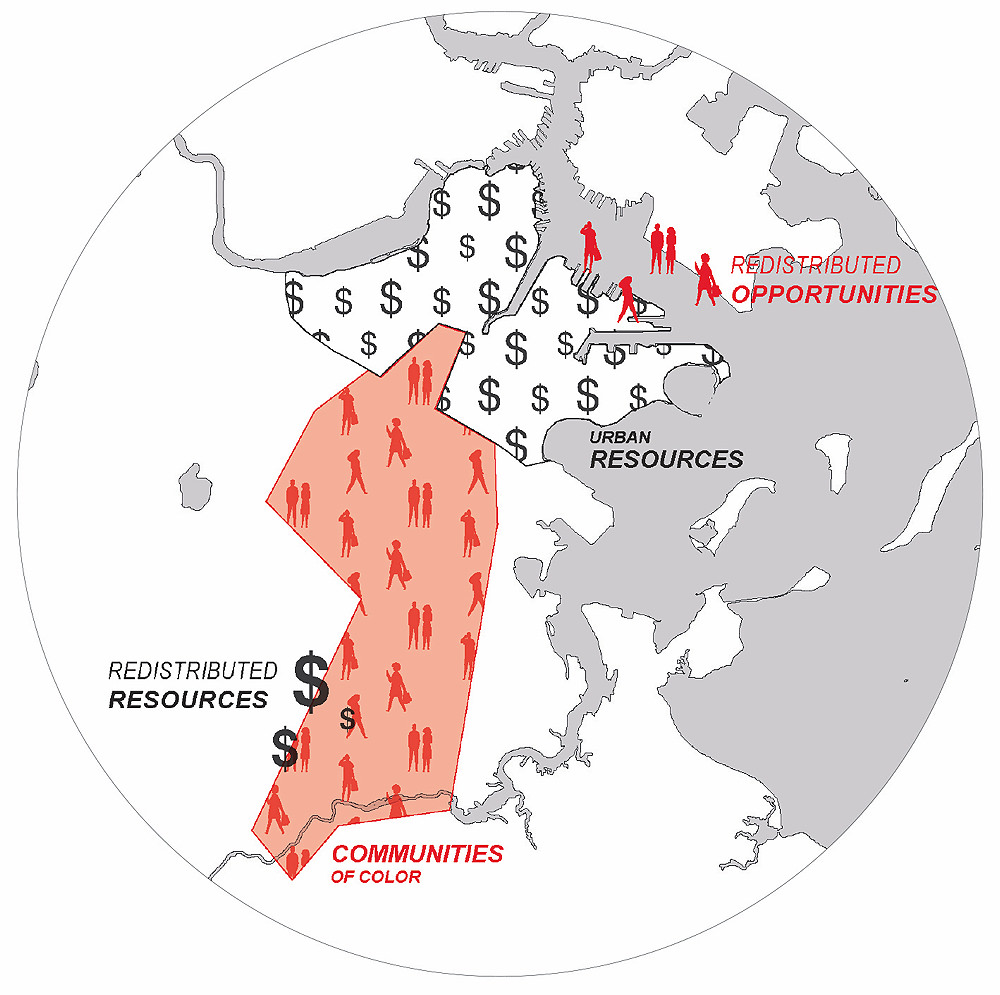

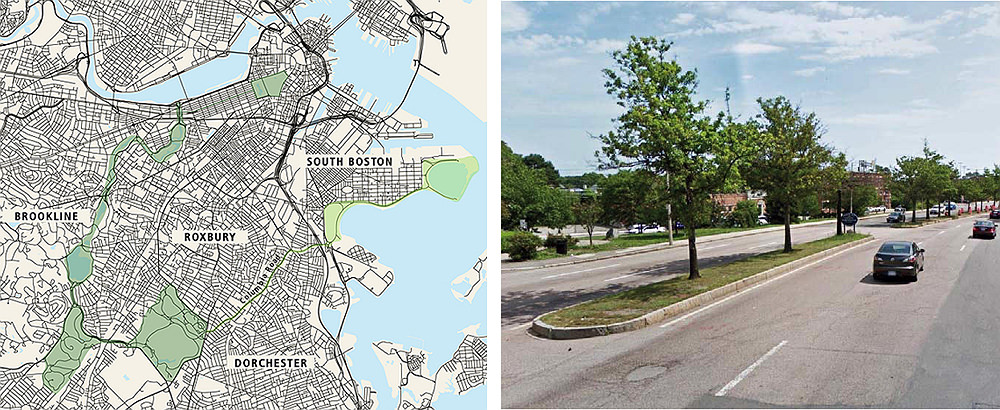

And the mishandled projects don’t exist in a vacuum. They often are planned in cities with long histories of segregation, an outcome of what Gray calls “a highly adaptive white supremacist, capitalist racial ideology.” This ideology, he says, has justified policies that have historically destroyed black communities: redlining, racial terrorism enforced through Jim Crow laws and community massacres, community impoverishment through blockbusting and predatory lending, and targeted community removal for urban-renewal and federal-highway programs. Renewal projects between 1950 and 1980 meant to address urban neglect often exacerbated these issues instead, he explains. In Boston, urban renewal helped push the city’s black population into a wedge-shaped area with dramatic disparities in wealth, education, life expectancies, and job access compared to other neighborhoods even today. The life expectancy of a resident in Back Bay is 92 years. In predominantly black Roxbury, a half-hour T ride away, life expectancy is 58 years.

Gray believes budgeting is the center of power. “Once a project is funded,” he says, “you’ve already made it exclusive.”

To confront these social inequities, Gray thinks considerations of racial equity must be pushed to the forefront of the design process—when budgets are being decided. “That’s really where the center of power is,” he asserts. “Once a project is funded…you’ve already made it exclusive” even if attempts to make the process inclusive are made later. He aims to convince his clients that letting community leaders participate in allocating funds is worth the effort, and doesn’t mean relinquishing power. “It’s not that you’re giving something away,” he says. “You are ensuring the success of the city as a whole, which actually ensures the success of your project and the community that you’re building it within.” The Uptown Cincinnati project backs that up. By creating “productive friction” among groups not used to working side by side, he had gotten government, private interests, and residents to agree. In the end, this major investment in infrastructure paid off not only for the private sector, but also for the city and the surrounding communities.

Meanwhile, Gray’s urban-design process was evolving, too. After becoming an assistant professor in 2015, he was approached by students to advise “Map the Gap,” a student-led initiative that examined three cities’ histories with urban renewal, racially divided education systems, and unequal transport networks. “I was never the race guy,” Gray says. But through his work with students, he began thinking of race not just as one consideration among many, but as a factor that had to be explicitly acknowledged before unequal systems could be changed. He began incorporating race not just into his research and teaching, but also into his practice.

Since Gray began Grayscale Collaborative in 2015, he’s used Boston as a testing ground. “The pre-distribution of power means finding and identifying points of a process where power is exercised and decisions are made,” he says, “and making sure that people are involved centrally at that point.” And because no two projects have the same stakeholders, each design process must start anew.

Working with the Emerald Necklace Conservancy on an equity agenda, Gray has helped assess how faithfully the group is continuing Frederick Law Olmsted’s vision of equally accessible public space as the 2022 bicentennial of his birth approaches. On learning that the Conservancy’s board of directors largely lived and worked in affluent areas containing well-funded sections of the park like Jamaica Plain and Fenway, he helped form a representative committee of neighborhoods, staffed by community members who live within walking distance of the park and who are already doing work on environmental and racial justice, and health equity. Though the final section of the Emerald Necklace, along Dorchester’s Columbia Road, remains incomplete more than 150 years after the rest of it was built, Gray hopes that with a more representative board, the project in the majority-black neighborhood with little existing green space might soon be realized.

In the Seaport district, Gray is working on interventions aimed at turning the city’s newest—and whitest—neighborhood into the kind of diverse area many had hoped for. With the Massachusetts Port Authority, he’s trying to execute a straightforward idea: “Introduce new programs and new people into a space where they don’t feel invited or welcome, and inviting them to actually decide what happens.” By funding public art and performance projects by artists of color, he hopes to attract residents from other parts of Boston to a place they might not otherwise visit. And by adjusting the existing land-disposition process, Massport and Gray have required developers to allocate a small percentage of their budget for “public-realm activation”: funding projects early in their development to see which resonate and which don’t. The requirement, he believes, will align private and public interests, pushing developers to experiment with public-oriented projects.

He emphasizes that these processes are experiments. To really push equitable design forward, lessons learned in one project need to be shared. In 2018, Gray served on the committee to award the GSD’s biannual Green Prize, which recognizes one project that “demonstrates a humane and worthwhile direction for the design of urban environments.” He came in adamantly opposed to one nominee, the High Line. The glitzy park in Manhattan had been heralded for its beauty and innovative use of a defunct elevated railroad line, but it had also been panned for its role in gentrifying the surrounding area and displacing residents. “The High Line is complicated,” Gray said while sitting on the award panel. “And there were some of us on the committee—at least myself—…very committed to selecting a great project, but also very committed to it not being the High Line.”

Gray has now turned student initiative into an entire course…that has only sharpened his own design process.

But he changed his mind when he saw a real reckoning from the developers after the project’s completion. Displeased to find that only 22 percent of its visitors were people of color in an area with a much higher population of non-white residents, the High Line’s board invested $4 million in programming, doubling the share of non-white visitors to the park within a few years. And rather than argue with critics, the developers instead established the High Line Network, which helps groups working on 37 infrastructure-reuse projects in the United States, Mexico, and Canada achieve the park’s successes without repeating its failures. “The High Line should be seen not merely as an infrastructural program that produced economic gains for the city and private developers,” Gray wrote. “It also exists and perhaps has had its greatest impact because of the agency-driven, activist agendas that brought the project about and that continue to propel its equity mission.” In Gray’s course “Urban Design and the Color Line,” his students work directly with these groups, helping them navigate complex bureaucracies without sacrificing racial-equity goals. Once inspired by his students to incorporate race more explicitly in his work, Gray has now turned student initiative into an entire course—a workshop that has only sharpened his own design process.

It’s not just Gray’s work that is always changing. COVID-19, he says, has hit the design industry hard. Some organizations that rely on philanthropy and donations to carry out their projects have had to scale back or postpone their plans. But the pandemic has also brought issues of racial inequity to the forefront. Responding to pressure from citizens, governments are increasingly willing to engage with issues of race and inequality in design. Once seen as inconvenient hurdles to clear, these issues are now top priorities. And Gray has seen the beneficial results.

The Innovation Corridor—a project opposed, then supported, by community organizations—is under construction now in Cincinnati. Since the interchange opened for use in 2017, several buildings have been completed, including the UC Garner Neuroscience Institute, a $6-million outpatient center, and the Avondale Town Center: a mixed-use development with 69 residential units, 75,000 square feet of commercial space, and a health clinic.

But the biggest successes of the work thus far, he says, were unexpected. Almost a decade after different interests were brought together to negotiate the future of the development, the connections among the city, its institutions, and its residents remain strong. The relationship has led to two more projects: the first market-rate housing development in Avondale since 1990, and forgivable loans of $35,000 for residents to improve their homes and avoid gentrification-induced displacement, funded by Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. They’re outcomes that few would have imagined years earlier: incentives to stay rather than impositions to leave. “The relationship building that is taking place with the community partners in Avondale, if you had said that to me 10 years ago, I would have said no way,” said Sandra Jones Mitchell, president of the Avondale Community Council, in an interview last fall. “But it has changed. It has changed a lot.”

The process, it seems, will only continue.