On the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, interspersed amid Michelangelo’s famous frescoes—God’s fingertip reaching out toward Adam’s, the sun and planets coming into creation, Adam and Eve banished from Eden—is a series of 10 bronze-painted medallions depicting scenes from the Old Testament. Relatively monochromatic and overwhelmed by the bright figures that surround them, these smaller paintings are easy to miss, especially for tourists looking up from the floor roughly four stories below, crowded shoulder to shoulder and shuffled steadily toward the exit by Vatican Museums docents. “From that distance, it looks like a dot in the ceiling,” says photographer and publisher Nicholas Callaway ’75, “but these are fabulous trompe l’oeil paintings—they resemble hammered bronze shields—and the line technique is astonishing and radical. You could spend a lifetime staring at the details.”

Nicholas Callaway

Photograph courtesy of Nicholas Callaway

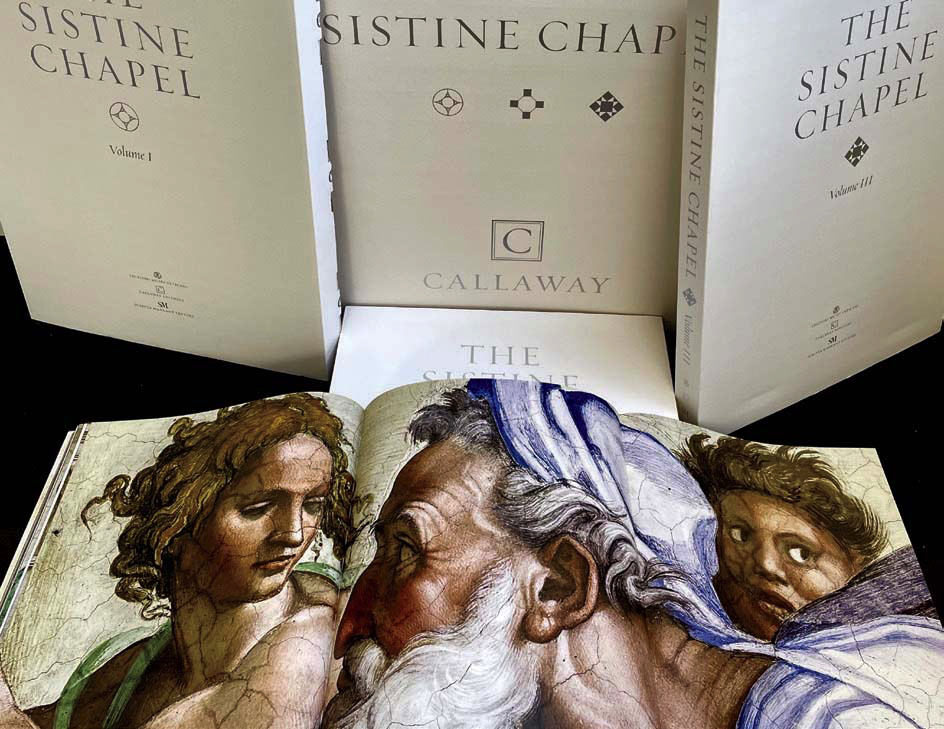

That’s just one discovery among many, he says, in The Sistine Chapel, released by his publishing company, Callaway Arts and Entertainment, late last fall. Although the title is simple, the book is anything but. A three-volume set that reproduces every painting in the chapel at actual size, in detailed plates, it measures 24 by 17 inches and weighs 75 pounds. Its 822 pages include foldouts as long as 62 inches. (When Callaway hoists one volume onto his lap during a video call, the opened book fills the screen, as he peeks over the top edge.) Each book is bound in silk and calfskin leather, by the only bookbinder in the world who can hand-sew works this large. Only 600 copies were printed in English; each costs $22,000.

The project, a collaboration with the Italian art publisher Scripta Maneant, was years in the making. It took a year just for Callaway to persuade Vatican officials to let him digitize the artwork. Then, a team of photographers spent 67 nights on scaffolding, documenting every inch of the frescoes by Michelangelo, as well as others in the chapel painted by Botticelli and other Renaissance masters. The team created more than 270,000 ultra-high-resolution digital images that were stitched together to produce richly detailed photographic prints revealing every brushstroke, daub of color, and hairline crack in the plaster. “It’s an immersive experience,” Callaway says. “These are not really reproductions—it’s an art experience between covers.”

Altogether, The Sistine Chapel took half a decade to complete, but Callaway pushes its true beginning even further back. The book is the culmination, he says, of 40 years in the publishing field: “our ultimate, biggest ambition.” Callaway was 27 when he founded Callaway Editions, focusing on photographic books. Two years later, in 1982, the New York-based company, still a tiny upstart, published Alfred Stieglitz: Photographs & Writings, a massive anthology of the photographer’s images, coinciding with a retrospective exhibition at the National Gallery of Art. In a New York Times review, critic Hilton Kramer called it “dazzling” and “the most beautiful book ever to be devoted to [Stieglitz’s] work.”

In the decades since, Callaway and his enterprise branched out in wide, and sometimes wild, directions (hence its broadened name). Its catalog includes Madonna’s controversial, transgressive 1992 book, Sex, and the 2018 oddity Theophrastus’ Characters: An Ancient Take on Bad Behavior, a new translation of a fourth-century b.c.e. text that earned praise from critics and classicists. More than 25 years ago, Callaway began collaborating with artist and toymaker David Kirk (a creative lark, after buying one of Kirk’s toys for his daughters) on Miss Spider’s Tea Party, a 1994 children’s book that grew into a series and a television show, and then a digital app (also developed by the company). “We’ve always tried to be on the cutting edge of technology and digital technology,” he says. That’s one thread tying Miss Spider to the Sistine Chapel. “It’s a huge part of my passion, these new digital-photography technologies that are so extraordinary that they can permit a level of quality that’s never been possible. There’s always been a connection between traditional craftsmanship and artistic creation, and the latest technology.”

A photographer capturing close-ups for the book

Photograph © Vatican Museum

Callaway has been taking pictures since he was 14, and he arrived at Harvard torn between two consuming interests: photography and classics (Joseph Campbell opened his eyes to the ancients). In Cambridge, he studied both: his mentors were the great translator Robert Fitzgerald and philologist Emily Vermeule, as well as legendary photographer Minor White at MIT. But it was an unlikely friendship with painter Georgia O’Keeffe, whom he’d idolized since high school (“She was my Helen of Troy,” Callaway says), along with Stieglitz, her husband, that set him on his professional path. In college, he made a photograph of a peony that reminded his girlfriend of an O’Keeffe painting. “Why don’t you send it to her?” she suggested. He did—and got a letter back, thanking him for the beautiful picture. In 1973, when O’Keeffe received an honorary degree, Callaway bought a peony at a flower shop and elbowed his way to the front of the crowd in Harvard Yard, pressing the flower into her hand as she processed past. On stage, she held it throughout the convocation ceremony.

Some months later, making plans for a photography trip to the Southwest, he wrote to O’Keeffe again. This time, she invited him to visit, and he spent days with her in New Mexico, at her home in Abiquiu and the 21,000-acre Ghost Ranch. “It was extraordinary,” he says. “Transformative.” After college, he moved to Paris on a Harvard summer fellowship and then was offered a job as the inaugural director of Zabriskie Gallery, an art gallery dedicated to photography and housed in a former fifteenth-century cheese shop. For two years, he mounted exhibitions by artists like Henri Cartier-Bresson, Ansel Adams, Berenice Abbott, Harry Callahan, Brassaï, Man Ray, and, of course, Stieglitz. “Cartier-Bresson, who was known as a hermit, used to come and hang out in the gallery,” he says, “because we were celebrating this undervalued great art form that was just beginning to be recognized.”

A three-volume set, The Sistine Chapel measures a massive 24 by 17 inches. The book itself is a work of art, Callaway says, and it comes with its own viewing stand.

Photographs courtesy of Nicholas Callaway

His experience in Paris and his friendship with O’Keeffe helped him win the contract for the Stieglitz book a few years later (the National Gallery exhibit photos were donated by O’Keeffe, the executor of Stieglitz’s estate). It also led him to One Hundred Flowers, an oversized collection of O’Keeffe’s own works, some of which were in private hands and had never been exhibited publicly. Callaway tracked them down using a typewritten 1940s catalogue raisonné that he’d discovered in the Archives of American Art, securing publication rights from the owners. It became one of the largest-selling art books in the world, with more than a million copies in print. “We did it by using her own principle,” he says: “That by taking something small and making it huge, we’re going to make you pay attention.”

Something similar guided The Sistine Chapel. “It’s Mount Everest, you know?” Callaway says. “The ultimate spectacle of its day. It’s one of the world’s great masterpieces, that people think they know. But they don’t know it, because they can’t fly up 68 feet to see it.” His book makes them pay attention all over again.