At first glance, the more romantic paintings by Alexander Gassel could simply be storybook illustrations. Entranced lovers stand in a boat rocked by waves. Angels crane against a dark night. The swirling Madonna envelops her child amid blossoms. Yet the longer Lana Sloutsky, curator of the Museum of Russian Icons, explored Gassel’s works, the deeper, and more personal, his mythical and biblical imagery became. “He has,” she says, “all these different spheres of influence in the way he developed his visual language through traditional Russian Orthodox iconography and avant-garde, Art Deco, European post-Impressionists.”

Doors to the Sky

Image courtesy of Alexander Gassel and the Museum of Russian Icons

Sloutsky mounted “Painted Poetry: Alexander Gassel, a Retrospective” (through mid July) to highlight the contemporary artist’s eclectic works. Look specifically for glimpses of styles associated with Gustav Klimt, Marc Chagall, Wassily Kandinsky, and Erté. Children will enjoy the colorful, dramatic scenes, while adults tune into Gassel’s tenderness and nuanced balance of hues and rhythmic contours akin, Sloutsky adds, “to music on canvas.”

This artistic gamut stems from Gassel’s Russian heritage (he immigrated to the United States in 1980, with $10 in his pocket) and professional training in Moscow as an iconographer, conservator, and art historian. Yet he has always created his own art; the paintings on exhibit were produced within the last two decades, most of that time spent working as a conservator at the museum itself, located in Clinton, Massachusetts. Following traditional icon-painting techniques, he uses egg-yolk tempera, grinding his own pigments from stones and minerals. Splashes of rich color, and his meticulous detailing, animate scenes of rural Russia, where he spent youthful summers. Country Life and Old Village in the Winter also carry a prevalent theme: the coexistence of suffering and joy. Poverty, hard labor, and drinking “were serious problems,” Sloutsky says, “and yet, at the same time, you see people dancing and singing, people collaborating.”

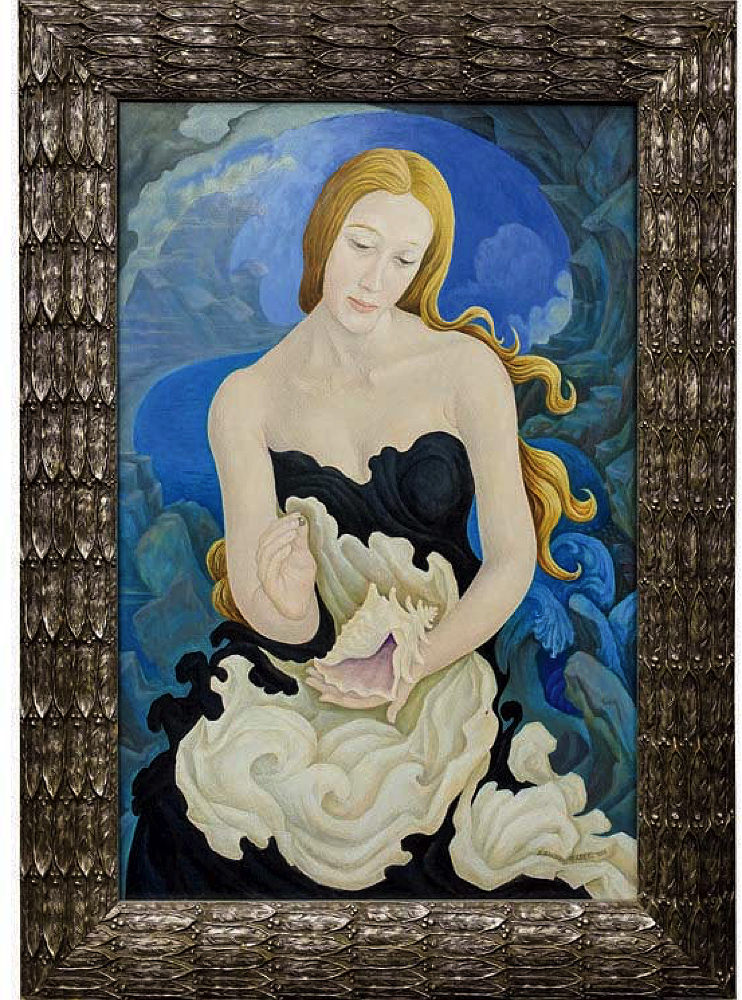

Sea Nymph

Image courtesy of Alexander Gassel and the Museum of Russian Icons

This underlying dichotomy is inherent, too, in Gassel’s depictions of the Madonna, and in Two Angels, Sea Nymph, and other works. In 2001, his only child, Marina, died of cancer, leaving behind her eight-year-old daughter. “It is a tragic story,” says Sloutsky. “The doctors did everything they could, but it was just too late.” Thus, the figures of blonde women in Gassel’s works post-2001 honor both mother and child. Dressed in flowing white garb, with trailing locks, their bodies are often entwined, their faces pure and alive. In Doors to the Sky, a woman in a gauzy gown stands at the head of a staircase, her hands on golden doors, flanked by silver Art Deco columns. Though her body is turned to the starry night expanding above and behind her, her face, expressing resignation and longing, is turned back, toward the viewer, the painter, her father, as if to say farewell.