The Ten Year War: Obamacare and the Unfinished Crusade for Universal Coverage, by Jonathan Cohn ’91 (St. Martin’s, $29.99). A veteran health-care reporter recounts the making of the Affordable Care Act. The value lies less in each detail than in recalling that any epochal exercise in policymaking is a process—and a window on the country’s clunky politics. The ACA, Cohn concludes, is “a highly flawed, distressingly compromised, woefully incomplete attempt” to establish a right taken for granted in all other developed countries—and “the most ambitious and significant piece of domestic legislation” to be enacted in 50 years: “In America, this is what change looks like.”

Mom Genes: Inside the New Science of Our Ancient Maternal Instinct, by Abigail Tucker ’02 (Gallery Books, $28). Note the informal title and the “inside” of the subtitle. Tucker examines what is being discovered about maternal feelings and mothering by immersing herself in the field, but refracting what experts say through her own experiences, winningly told: “Being a mom…is often intensely miserable business. Having been internally rejiggered to find babies immensely rewarding, we are also made intimately aware of all their cues” and their states, “which involve grocery store tantrums and night terrors at least as much as story time smiles and goodnight kisses.”

Plunder: Napoleon’s Theft of Veronese’s Feast, by Cynthia Saltzman ’71 (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $30). “Napoleon Bonaparte was a plunderer of art, one of history’s most accomplished,” writes Saltzman, of the cultural project accompanying his political ones. She focuses on the 1797 theft of Paolo Veronese’s Wedding Feast at Cana, from the wall of a monastery in Venice, where it had been painted more than two centuries earlier in a superb space proportioned by Andrea Palladio. The Louvre, one is reminded, did not just emerge as a staggering museum (the Veronese hangs opposite the Mona Lisa), and cultural appropriation is not solely a problem of the past.

Shape, by Jordan Ellenberg ’93, Ph.D. ’98 (Penguin, $28). The author of How Not to Be Wrong, on mathematical thinking, who professes at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, here dusts the cobwebs off geometry—and explains its relevance to “information, biology, strategy, democracy, and everything else,” per the subtitle. He is up to the engaging standard of his prior book. Not many such tomes start with an exegesis of Wordsworth, and then a deep plunge into Abraham Lincoln immersing himself in a problem from Euclid. Even without the sections on the math of pandemics, almost anyone is likely to enjoy Ellenberg’s prose, and mind.

A Pattern of Violence, by David Alan Sklansky, J.D. ’84 (Harvard, $29.95). Stanford’s Morrison professor of law argues that mass incarceration and the challenges of police reform are linked by “how the law understands and responds to violence.” Terming an individual’s impermissible action as “violent” now makes it a much more serious crime—even as “a decline in the salience of violence in the rules that govern law enforcement” (by placing such conduct in situational contexts) skews perceptions, reinforces inequities, and threatens the legitimacy of law itself. An important examination of the ways in which “[s]implistic ideas about violence can lead the law astray.”

The Amazon, by Mark J. Plotkin, A.B.E. ’79 (Oxford, $16.95 paper). Despite the annoying constraints imposed by the “What Everybody Needs to Know” format (a series of seemingly random questions and answers, rather than a narrative), there is a lot to learn, and value, from this guide, by an expert immersed in his subject. For example, it perhaps helps to visualize a place that remains abstract and remote to most humans to read that the region’s role in determining global climate rests upon its “almost 400 billion trees.”

Thinking Inside the Box, by Adrienne Raphel, Ph.D. ’18 (Penguin, $18 paper). If you, like us, missed its original publication during this past mixed-up year, paperback release of this journey through crossword puzzles is a welcome second chance. The author, obsessed by her subject from an early age, plumbs the first puzzle (1913), puzzle-making and -editing, etc. If you indulge, you are in good hands with a guide who “even take[s] a crossword-themed ocean crossing aboard the Queen Mary 2.”

The Education Trap: Schools and the Remaking of Inequality in Boston, by Cristina Viviana Groeger ’08, Ph.D. ’17 (Harvard, $35). An historian of education and work, now at Lake Forest College, peers back into the radically unequal Gilded Age to discover that schooling—thought to be a leveling, egalitarian force—in fact served to undercut unionized workers, privilege management, and erect gates to control entry into a better paid, and better, life. Given contemporary evidence that the pattern is repeating itself, Groeger’s narrative points to education, labor empowerment, and other measures, in concert, to promote greater equity today.

The Empathy Diaries: A Memoir, by Sherry Turkle ’69, Ph.D. ’76 (Penguin, $28). The MIT scholar who has done more, perhaps, than anyone to examine the costs to human connection of online communications, now examines what empathy really means, and how it came to mean that for her, in a reflective memoir. It ranges from her early memories of a closeted family through the challenges posed to a woman scholar in fields then bristling with maleness. Harvardians of her era may remember their own discoveries in those days, much as Turkle—in Laurence Wylie’s reading course on the “vexing” Derrida, Foucault, and Lacan—recalls the “conspiratorial atmosphere of our meetings.”

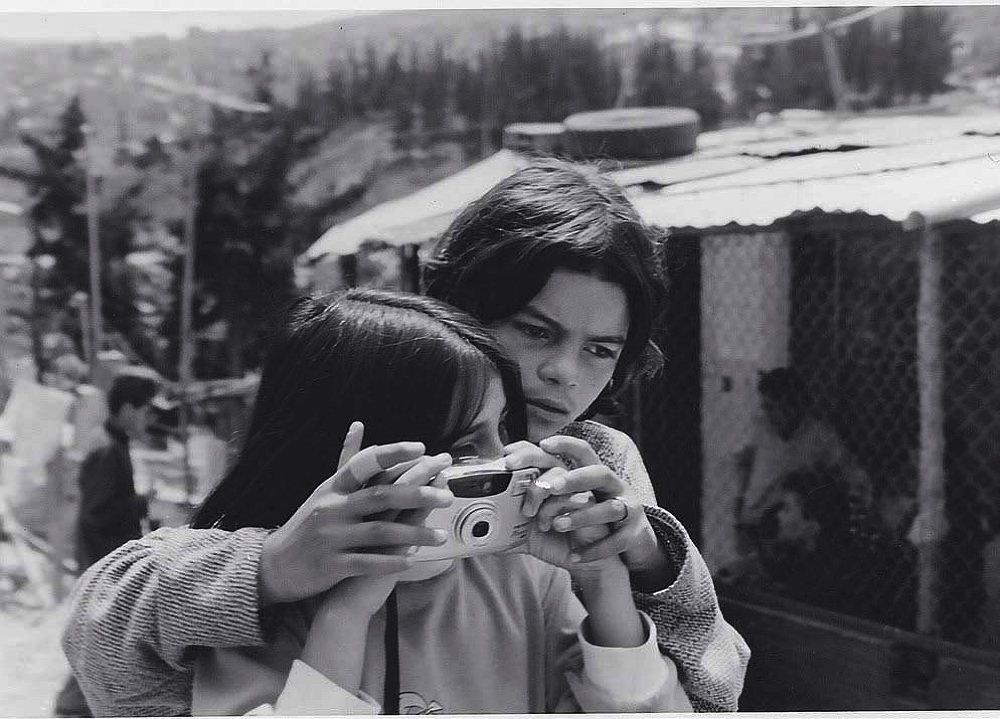

Eyes of the beholders: photo by Ximena Vargas, 2005, from the participatory Shooting Cameras for Peace project

Courtesy Fundación Disparando Cámaras para la Paz

Shooting Cameras for Peace, by Alexander L. Fattal, Ph.D. ’14 (Peabody Museum Press, $39.95 paper). The author, then a Fulbright Scholar (now at UC, San Diego), founded Disparando Cámaras para la Paz (Shooting Cameras for Peace) in 2001, in the El Progresso neighborhood outside Bogotá, Colombia, during the protracted armed conflict there. This album of “participatory media,” featuring work by young people taught photography, makes the resulting, riveting images available for consideration on their own merits, whatever the viewer’s political proclivities.

Laura Nader: Letters To and From an Anthropologist (Cornell, $39.95). Selections from a lifetime of correspondence, selected by the author, Ph.D. ’61, professor of anthropology at Berkeley, who writes modestly that they “give a glimpse of academic life mostly unseen…by the public at large.” Browsing reveals nuggets: a legal-services staffer who saw the PBS special Little Injustices, on Nader’s work in Talea, Oaxaca, for instance, wrote describing her own work, “exclusively dedicated to the representation of old men and women” in the United States who scrape by as they “buy shelter, heat, light, food, and communication—nothing more.” A subject for anthropological analysis, domestically, if ever there were one.

Digital Body Language, by Erica Dhawan, M.P.A. ’12 (St. Martin’s, $28.99). Now that everyone might, if lucky, be about to get off Zoom a day or two a week, a “twenty-first-century collaboration expert” advises on building trust and connection, distance be damned. For example, “engage in digital watercooler moments.” Time to get back to the office!

The Unspoken Rules, by Gorick Ng ’14, M.B.A. ’18 (Harvard Business Review Press, $26). There is a burgeoning literature on adapting institutions to newcomers (like first-to-college students; see “First-Gen Inclusion and Belonging,” January-February, page 22). The author, a researcher on the H.B.S. Future of Work Project and Adams House resident tutor, looks through the other end of the telescope, offering a guide to the “secrets to starting your career off right.” Its practical advice is generally applicable, but the approach—shining light on invisible norms and assumptions—might, one hopes, prove especially valuable for those doing so from the least advantaged backgrounds.