At a time when the federal government seems distant and Congress gridlocked by partisanship and the filibuster, is there another way to ensure the people’s voice is heard? Daniel Carpenter thinks so: his study of citizens’ use of petitions in the past suggests that direct contact between the people and their representatives, complementing their occasional interaction in elections, might invigorate democracy.

Petitioning is an expeditious democratic tradition, used much more frequently in prior centuries, by which citizens can bring issues directly to governments. The practice of gathering signatures in support of a cause is alive and well in small New England towns, where citizens’ petitions can be used to place proposed bylaws on town-meeting agendas or annual election ballots, so townspeople can vote on them. But at the federal level, petitioning is no longer as common as it was in the nineteenth century. That has impoverished American democracy, says Carpenter, Freed professor of government, whose recent book, Democracy by Petition (Harvard University Press), provides a history of the practice.

As expressions of collective voice, petitions support procedural democracy by shaping agendas, he recently explained. They demand a formal response from the powerful—affirmative or not. Petitions can also recruit citizens to causes, give voice to the voteless, and apply the discipline of rhetorical argument that clarifies a point of view. Often, Carpenter says, the movements that petitions initiate leave legacies of organization larger than the people who started them.

By contrast, elections are limited in several respects. They are “highly blunt instruments,” he writes, “often between just a few candidates,” and thus “fall far short of a representative democracy.” Furthermore, “voters’ choices are not specific to particular policies or laws; they are often driven by judgments on the incumbent.” And “elections are episodic, whereas the voice of the people needs to be heard and integrated constantly into democratic government.” Petitions have historically done a good job of integrating that voice, he says, by performing the important political function of fostering social movements since the time of the Magna Carta.

In the United States, numerous petitions from the 1830s through the 1850s helped build support for the abolition of slavery, even when there was a gag rule on the subject in Congress. Similarly, women’s points of view as brought forward in petitions—expressed in roughly 2 percent of petitions to Congress before passage of the Nineteenth Amendment—played a significant role in securing the right to vote regardless of gender. Tenant farmers in New York State, laboring under the feudal patroon system, used petitions to free their farms from this autocratic arrangement. And Native Americans fighting encroachment on their ancestral lands frequently petitioned Congress for protection under the law.

But most political scientists have overlooked the importance of petitions as a mode of civic engagement. Carpenter, who came to Harvard 20 years ago as a scholar of bureaucracy, more or less stumbled across the topic while working on a book about executive-branch departments: he kept finding petitions to Congress and federal agencies advocating for administrative and regulatory reforms. He soon discovered that petitions were prompted by a broad range of concerns, and that they had the potential to provide valuable historical data about the popular voice and the formation of public opinion.

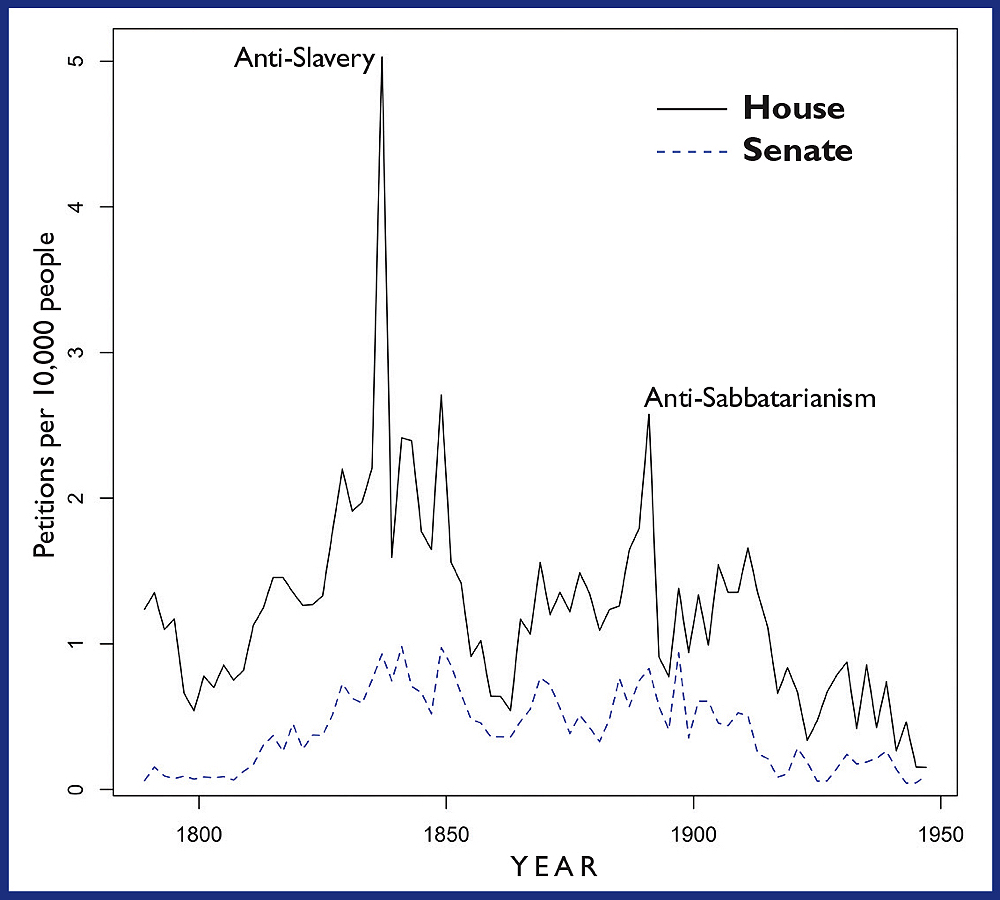

Together with University of Pennsylvania assistant professor of law Maggie Blackhawk, assistant professor of public policy Benjamin Schneer, and graduate student Tobias Resch, Carpenter has assembled a database of more than 537,000 congressional petitions from 1789 to 1949; that research informs his new book. One notable finding is that petitioning activity in the South, once equal to that in the North, declined steeply in the decades before the Civil War and again during the Jim Crow era from the late 1870s to 1965.

Why this happened merits further study, but Carpenter suspects that it is “an indicator of authoritarianism,” both of demobilization from below and a lack of responsiveness from above. From above, racialized authoritarianism fused parties and state governments, leaving white elites in charge with little need to respond to black and lower-class white citizens. From below, “The culture of petitioning becomes weak when the populace feels that their political representatives will no longer be responsive” to their supplications. Beyond this, petitioning by black Americans in the South courted the risk of state suppression.

The data reveal that “unenfranchised” people (women before suffrage, free blacks, indigenous peoples, and tenant farmers) were regular users of petitions, and their petitions were either tabled or referred onward at rates similar to those afforded franchised petitioners. For example, when in 1804 Deborah Sampson (who fought in the Revolutionary War disguised as a man) sought a pension for her military service, Paul Revere submitted a petition on her behalf to Congress, which granted her in the following year the first military pension awarded to a woman. (Pension requests are the most numerous type of congressional petition.)

Most importantly, the data “encompass peoples and places different from those centered in customary narratives….If newly freed men and women of color, still electorally negligible, could plausibly believe that their grievances and proposals would be heard by the highest organs of the land,” Carpenter writes, “then the United States had briefly achieved a kind of equality that eluded notions of contractual government. It was in that space of aspiration and strategy—in the confidence that the agenda of government was open to anyone, a belief that the signatures of hundreds and thousands could advance an appeal, a faith that memorial campaigns could generate fledgling organizations dedicated later to other, still noble purposes—that the petitioner’s democracy came into view.”

“I do think there’s an alternative model of democracy here,” he says, “that it is possible for a democracy to become too electorally centered.” When people think, “‘All we need to do is win elections, put our people in there, and let the machinery of government go to work’—without the dialogue between officeholder and citizen that democratic forms of government really need,” he continues—government by and for the people suffers. The United States may be in such a period now: Carpenter’s data reveal a long-term decline in petitioning that began after World War I. But he thinks the practice could be revived. “What I hope comes out of this project is a different understanding of democracy. Not one that rejects voting in parties, but that is complementary to it. This was the democracy that our ancestors lived—and that could be reimagined for our future.”