To safeguard access to weaponry, in 1794 the new federal government expanded an arsenal into a national manufacturing base in Springfield, Massachusetts. Starting with hand-crafted flintlock muskets, the armory produced and stored military small arms—becoming a 90-acre campus with a robust research and development unit until it was closed in 1968. At its peak during World War II, the armory operated 24 hours a day, with 14,000 workers (about 42 percent women), to turn out 3.5 million semi-automatic M1 rifles, designed by engineer John Garand. But the expertise of workers and the innovative machinery also led Springfield’s role in ushering “in the second, more technical engineering phase of the American industrial revolution and to a lot of our modern inventions, like bikes, typewriters, clocks, sewing machines, and screws,” says Amy Glowacki, program manager at what’s now the Springfield Armory National Historic Site. Inside the armory museum, house in an 1850 former arsenal, the center of a four-story spiral staircase still holds the the pulley system that once hoisted and lowered weaponry distributed by railcars.

Vintage muskets from the armory's collection

Photograph by Randy Duchaine/Alamy Stock Photo

Beyond that, the enormous exhibit space features some 1,200 small arms (mostly guns) and other objects from a collection that began, in 1866, as part of an on-site research library. That’s about one-tenth of the holdings, which also include documents, drawings, books, reports, oral histories, and thousands of photographs.

The towering double musket rack—the inspiration for Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s 1843 poem “The Arsenal of Springfield”—holds 645 M1861 Springfield Rifle-Muskets and three M1816 Springfield Flintlocks. In a case of revolvers and pistols, look for the popular 1942 single-shot “Liberator,” used by “by clandestine forces in Nazi-occupied countries.” There’s a sampling of signature World War I and II Axis and Allies weapons, along with the prized hand-crafted American Long rifles, and the famous Springfield ’03 rifle, made in the city for more than 30 years. Also on hand is modern weaponry, like the AK47, the main firearm used by the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong soldiers in the Vietnam War, and the “Wall of Machine Guns.”

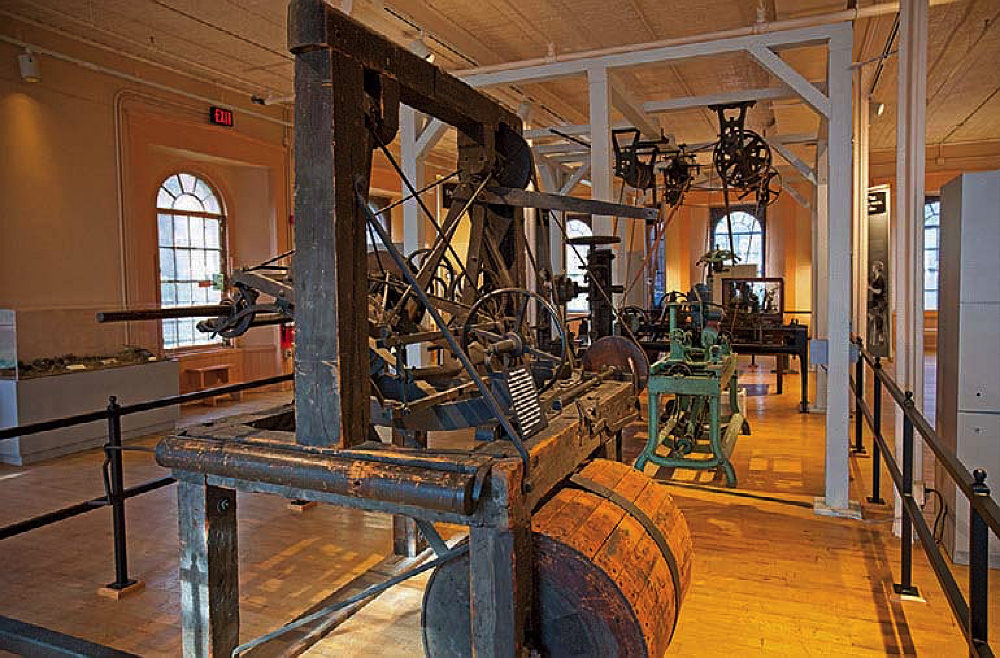

An 1820s Blanchard lathe that helped transform American manufacturing

Photograph by Randy Duchaine/Alamy Stock Photo

But you don’t have to be a gun or military aficionado to appreciate the historic site. Exhibits also highlight American craftsmanship, techincal innovations, and the contributions of generations of workers. When the armory began, it was essentially a proto-factory, through which the federal government up-scaled independent craft production; any worker could make a complete firearm, yet each part had to be hand-forged, filed, and finished to fit a particular musket. At the museum, compare early tools to the advent of machinery and interchangeable parts that revolutionized mass production—a transition effected in part thanks to the prolific, self-taught inventor Thomas Blanchard. His mechanical duplicating lathe in 1819 led to machines he developed at the armory, like the early 1820s Blanchard lathe (on display), which gave workers the unprecedented ability to replicate uniform wooden shapes, like rifle stocks. Rare archival portraits in the temporary exhibit “Art in the Everyday” underscore the many workers integral to the armory’s productivity; look especially for the touching 1943 picture of a patrolman with a nut-bearing squirrel on his arm. What draws people here, Gowacki says, is the breadth of American history reflected. Many visitors also have a personal connection to the place, as former workers or their descendants, and to armory-related military experiences. “It’s inspirational in terms of people coming together to serve this effort,” she says. “There’s a real sense of remembering and pride around what was accomplished here in Springfield and the influence it had around the world.”