Stephanie Gil’s first exposure to robot teams didn’t even happen on this planet. During her freshman year at Cornell, she interned with NASA and participated in the agency’s Mars Exploration Rover mission. NASA sent two robots named “Spirit” and “Opportunity” to different extremes of the planet. “I saw how robots could be our explorers and counterparts in faraway places that we can’t easily or safely reach,” she says, becoming inspired by how the robots worked in coordination to achieve a goal: “I realized that robot teams could also make a big difference here in our very own society. That, to me, was very cool, and I wanted to be a part of that.”

After earning her Ph.D. in robotics from MIT, Gil served as a visiting professor at Stanford and as an assistant professor at Arizona State University, winning awards from the National Science Foundation, the Office of Naval Research, and the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation for her research.

She joined Harvard as an assistant professor of computer science in July 2020, directing the REACT Lab (Robotics, Embedded Autonomy, and Communication Theory Lab), where she and her students develop and use technology to improve robot-to-robot and human-to-robot teamwork. Starting her new job at the height of the pandemic was daunting, Gil says, but Harvard provided her with “an amazing experience and transition.”

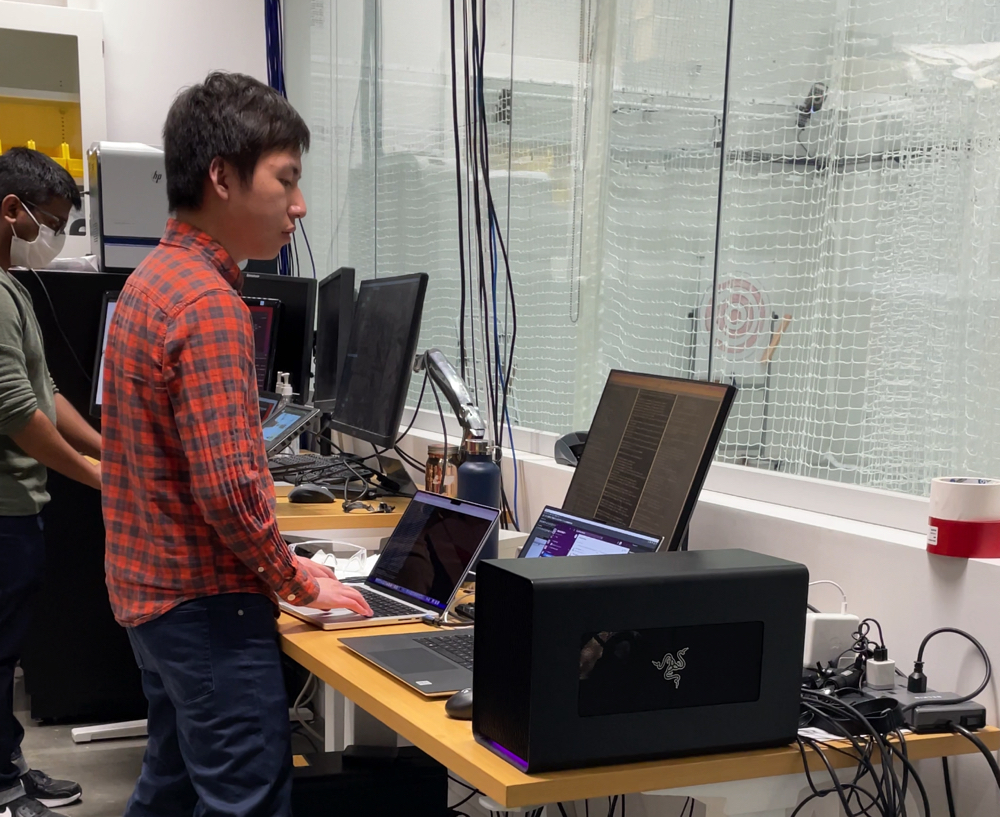

Professor Gil's graduate students working on a drone demonstration

Photograph by Kristina DeMichele/Harvard Magazine

Gil’s algorithms address such key questions as how robots share information and how each robot enacts an algorithm so that its actions are coherent within a group—enabling achievement of a shared goal more efficiently and accurately. “When we, as humans, coordinate as a team, we can achieve different things than when we work individually,” she explains. “The same thing holds for robots. For example, if you have a lot of robots around the city that are trying to coordinate deliveries, they can accomplish that goal a lot faster as a team. If we’re talking about search and rescue, the robots can share information about different parts of the environment with each other and with the search-and-rescue workers; and together… they can get a much more global view of what’s happening in an environment at one time. That reconnaissance is really important.”

One of the REACT Lab’s student projects pertains to search-and-rescue operations. In a simulation, one larger drone robot is designated as the “searcher,” deployed into an environment to assess the situation and find the “target,” which in a real-world setting would be the person(s) in danger. Once the target has been located, the searcher robot uses WiFi signals to alert a second group of smaller, on-the-ground robots so they can navigate to that location to provide care (see videos below).

What if WiFi is spotty, down, or not available? Well, “These robots can create their own networks,” Gil says, “a relay system to be able to send a message back, even if WiFi is weak or there is no existing infrastructure.”

While these search-and-rescue robots haven’t been deployed in a real setting yet, the lab is working with partners like the Arizona Department of Emergency and Military Affairs to gather “a very real connection with what they are seeing as boots on the ground when they’re going out on search-and-rescue missions,” Gil says. That helps the REACT staff learn how these robots could fare in extreme environments, so materials scientists can design survivable robotic devices.

In a demonstration, the drone finds the target, then guides the rovers to the target's location.

Graphic by Niko Yaitanes/Harvard Magazine

“As we start to think about putting these robot systems out into the real world, their robustness and their resilience is critical,” she says, emphasizing that having multiple robots assigned to a task is better than deploying just one: “If you have one robot and its sensors fail, then there’s not really much you can do, but if you have a team of robots and one breaks, then the others can adapt and pick up the slack.”

Malfunction is not the only risk. Robots are also susceptible to cybersecurity breaches. For example, she says, “Somebody could hack into the system and make one robot appear to be multiple robots in the network. They could therefore tilt the global decision of the team by looking like a larger contingent of the team.” Gil and her students always keep in mind that “robots can be just as vulnerable as our internet to things like hacking and misinformation,” so that plays a large role in how they design the robots’ algorithms.

Having multiple robots on a team instead of one yields a further defense against cyberattack, Gil says: “Since the robots can sense the physical environment around them, they have more channels through which they can cross-validate information.” Research into how the cyber and physical components work together has shown that this “really help[s] improve resilience.”

The REACT Lab is trying to address some of the practical obstacles to getting these robot teams in use and having them perform as robustly and resiliently as possible. “The colleagues here are really wonderful, and there is a strong connection to industry at Harvard,” Gil says. “We want our algorithms to…[have an] impact in the outside world and in society.” Gil received the Amazon Research Award in 2020, and says she plans on “leveraging the connections with Amazon” to make applications a reality.