In education, the post-COVID “return to normal” has been anything but straightforward. In fact, striving for a pre-pandemic status quo, Harvard and Stanford experts say, will perpetuate inequality and neglect the pressing educational gaps affecting children. Gale professor of education and economics Tom Kane, director of the Center for Education Policy Research at the Graduate School of Education, and Sean Reardon, E.D.M. ’92, E.D.D. ’97, a sociology and education professor at Stanford University and director of its Educational Opportunity Project, have taken the lead in studying the unequal impact of the pandemic on student learning. Through the Education Recovery Scorecard, a collaboration among researchers from Harvard, Stanford, Johns Hopkins, Dartmouth, and the testing company NWEA (formerly known as Northwest Evaluation Association), they provide the country’s first comprehensive analysis of student learning loss at the district level.

The Educational Recovery Scorecard was started in the spring of 2021 as the first pandemic-disrupted school year drew to a close, to measure how factors such as remote learning time and federal funding allocation influenced student achievement. Congress had just passed the American Rescue Plan, which, combined with other federal funding for pandemic relief, amounted to a $190-billion allocation for school districts to help students catch up. Despite the funding, there was little federal guidance or even within-state collaboration, and everyone was “left on their own,” according to Kane, and “winging it.” Reardon added, “13,000 school districts do…13,000 different things.” “We were realizing,” Kane said in an interview, “Holy cow, nobody knows how to help students catch up.”

“It just seemed like nobody was collecting these data” on test scores, school closure duration, COVID-19 death rates, and social media activity, said Kane. “So we said, ‘Okay, somebody’s got to do this. It might as well be us.’” He and his colleagues analyzed these data and many other metrics collected from nearly 8,000 school districts across 21 states, encompassing 26 million elementary- and middle-school students: roughly 80 percent of the United States’ public school K-8 students.

Math, reading, and history scores from the past three years show that students experienced a significant decline in learning during the pandemic. The team’s calculations indicate that by the spring of 2022, the average student was lagging by approximately one-half year in math and one-third of a year in reading.

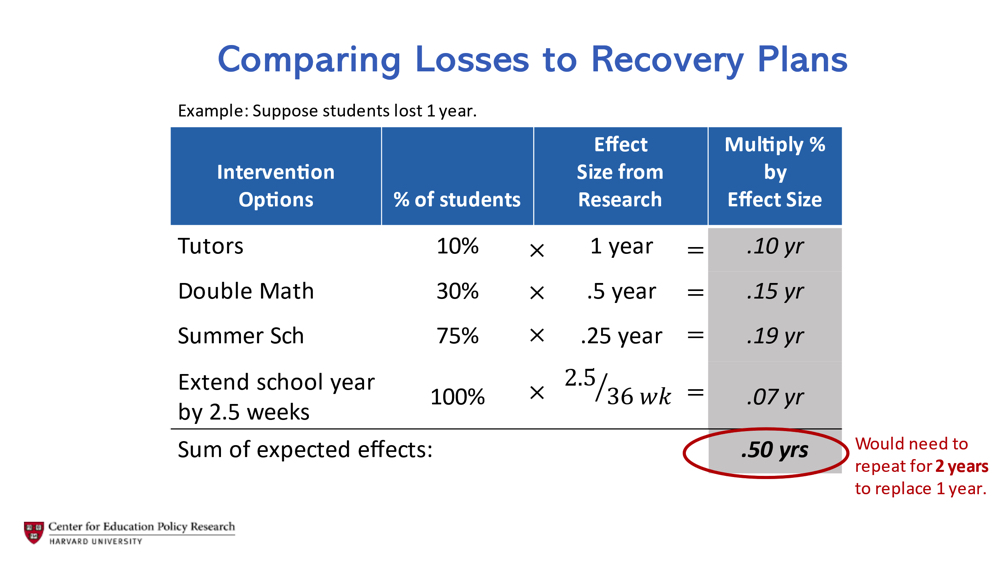

Comparing losses to recovery plans

Rendering courtesy of the Center for Education Policy Research

Furthermore, Kane and Reardon discovered that the pandemic worsened pre-existing educational, socioeconomic, and racial inequality along geographic lines. Students from low-income and predominantly minority districts fell further behind their peers from richer, whiter districts. “The pandemic effects weren’t equally visited on every community in terms of their consequences for children,” Reardon said. “I wasn’t surprised, but I was just dismayed and struck by how large the disparities were. In the most affluent communities in the U.S., on average, kids didn’t really fall behind much at all, but in the poorest and highest minority places…it’s as if they didn’t have any schooling for the better part of a year.”

Prior to the pandemic, the United States made “important progress” in educational reform that many “people aren’t aware of,” Kane said, such as a narrowing of black-white achievement gaps. “It’s been painful to watch a lot of that progress being reversed,” he continued. “Some 40 percent of the increase between 1990 and 2019 evaporated between 2019 and 2022.” Among the causes were the length of school closures, the prevalence of COVID deaths and resulting depression and anxiety in heavily affected communities, and curtailed social activities. “The pandemic was a public health and economic disaster that reshaped every area of children’s lives, but it did so to different degrees in different communities, and so its consequences for children depended on where they lived,” Kane and Reardon wrote in a May New York Times op-ed.

And “while students are learning again, they’re not making up a substantial amount of ground,” Kane said. “Students aren’t catching up. They’re not losing more ground but they’re not catching up.” Reardon warned that this cohort of students “may be at a disadvantage as they go into adulthood.”

The solution, Kane and Reardon emphasized, doesn’t involve “hurrying up.” “One of the barriers, ironically, is the desire—the instinct—to get back to normal,” Kane said. “We’ve got to go far beyond normal to help students catch up.” Instead, he suggested that the only way students can make up for lost ground is to provide additional instructional time through various means, such as tutoring during the school day, extending the school year, providing summer school options, and doubling math classes.

Reardon expanded on these suggestions, emphasizing that while scores offer some data, it is crucial to acknowledge that “the pandemic was a totalizing experience that affected every aspect of kids’ lives.” “It’s important to think about the whole child’s needs, not just their academic needs,” he said: their social lives, extracurricular activities, mental health, and stress. “They need counseling,” he continued, “they need things to help them make sense of the pandemic and develop some social-emotional skills that they may not have had a chance to develop because they were isolated.”

Reardon said that there’s “a real possibility” these adverse effects could be permanent. When he and other researchers looked at the past 10 years of test scores, they found that “when third or fourth graders fell behind, they were still well behind into eighth grade.” He continued, “Unless we have some sustained systematic efforts…you sort of bake in that extra inequality into this cohort going forward.”

“Education is a civil rights issue of our time,” Kane said. “It will be the way in which we make a difference in preserving social mobility and changing students’ lives.”