New Englanders know them well: the iconic stone walls that border roads, fields, and old farms are easily taken for granted, seemingly as natural as pine forests and babbling brooks. Yet the oldest “stone fences,” as they were once called, were laboriously created to safeguard crops and contain livestock, as Concord, Massachusetts, ecologist Richard T.T. Forman has found out during recent years of serious trail-walking. He’s identified numerous types of these relics, explaining when, why, and how they were constructed in “Deciphering Concord’s Old Stone Walls and What They Indicate,” published by the Concord Land Conservation Trust last year. “Envision the English settlers in Concord coming in 1635 and seeing the forests just covered with these rocks,” he says during a walk through the Newbury Field conservation land. They cleared land for crops and timber but when cows and sheep arrived, sturdy fencing was required. Oxen hauled the glacier-deposited round stones out of the woods on sleds, then people piled them up, from large to small, in practical and pleasing configurations. In Newbury Field, the wall that looms perpendicular to the woodland trail, about a three-minute walk from the entrance, “was for cows because it’s shorter,” says Forman, professor of advanced environmental studies in the field of landscape ecology, emeritus, at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design. “Higher fences were for sheep because they can jump.” He jabs at the humus with a metal rod, hunting for sunken basal stones that farmers likely placed there sometime between 1675 and 1775.

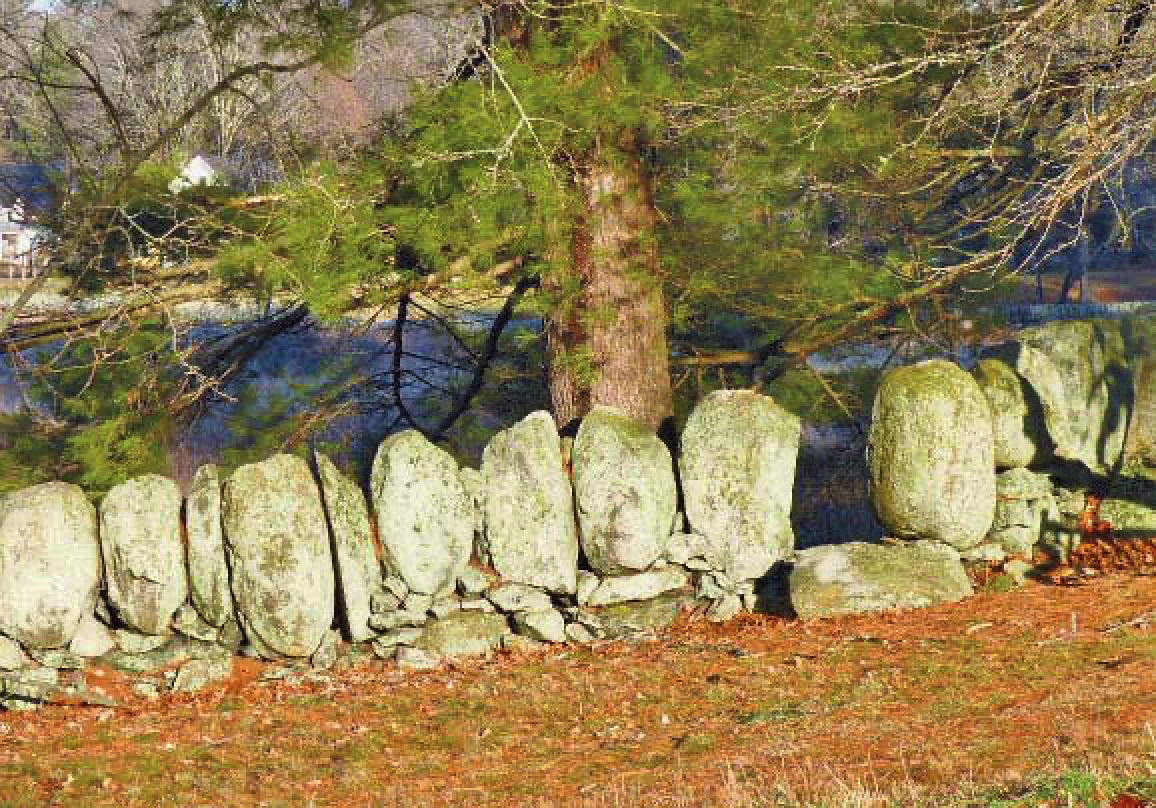

A decorative wall from the 1890s at Nashawtuc Hill

Photograph by Richard T.T. Forman

He’s identified numerous stone structures, from those built for barn and cellar foundations, impounding stray livestock, and altering stream-flows to the “double cultivation” walls featuring a V-shaped trough where farmers tossed small stones that surfaced in freeze-and-thaw cycles. Such industriousness meant that by the 1850s, a dearth of good stones led residents to cannibalize old walls to make new ones, leading to more modern walls made of a jumble of hand- and machine-cut rocks. But a walk through any New England woods grown up on former farmland will still likely reveal stretches of lichen-layered stone of walls, some laid down centuries ago. And those are, he says, “a treasure to discover.”