Within a few shelves at Tozzer Library, the boundaries between academia and daily existence blur. Here, hundreds of ordinary items from 2000s Indigenous life—zines, comics, graphic novels, cookbooks, board games, and language learning tools—exist alongside some of the world’s oldest, most comprehensive anthropology and archaeology collections. The brainchild of Diné curator Julie Fiveash, Harvard’s inaugural librarian for American Indigenous studies, the Indigenous Knowledge Collection transcends the confines of scholarly texts and embraces Native voices in all forms.

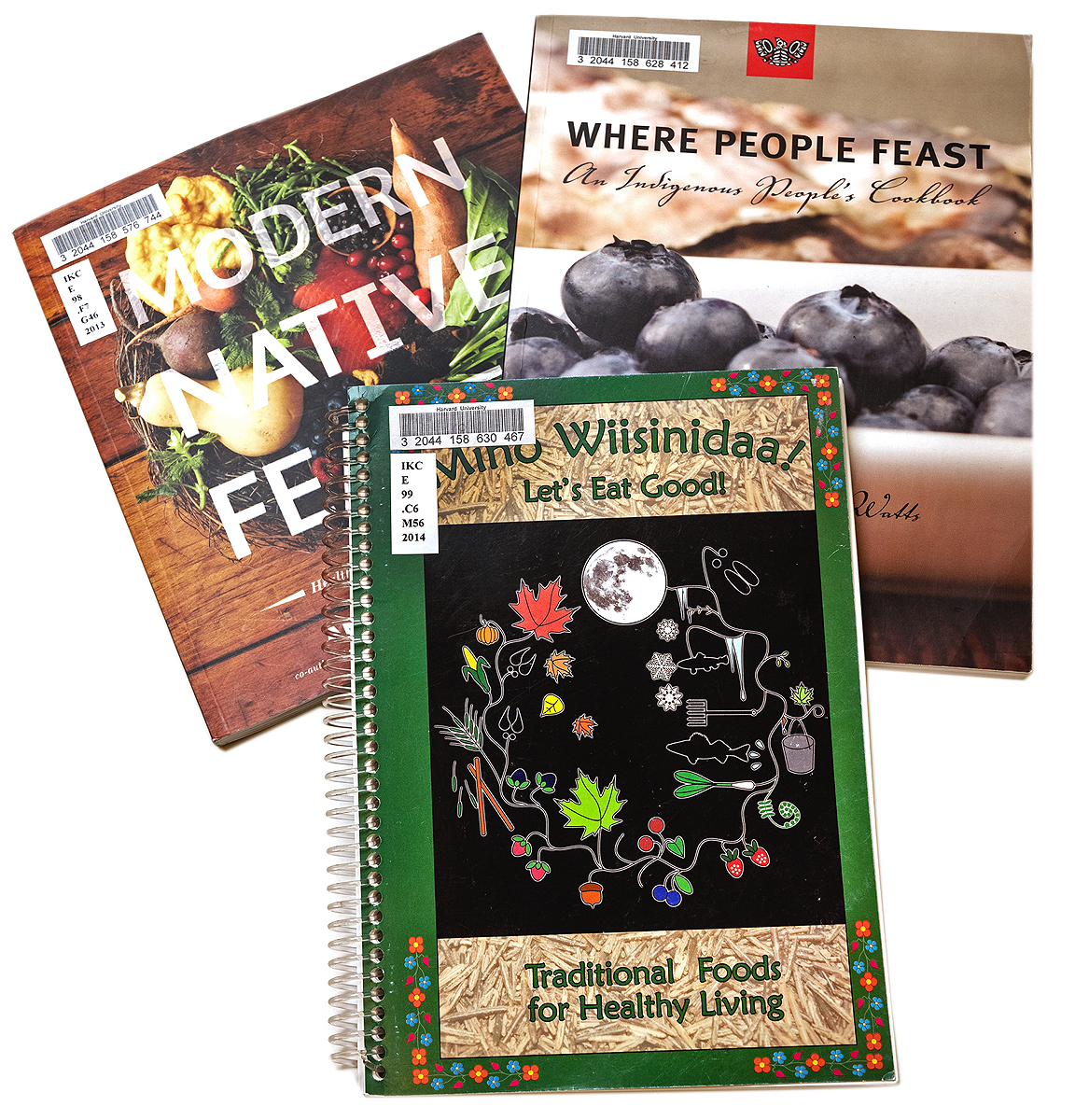

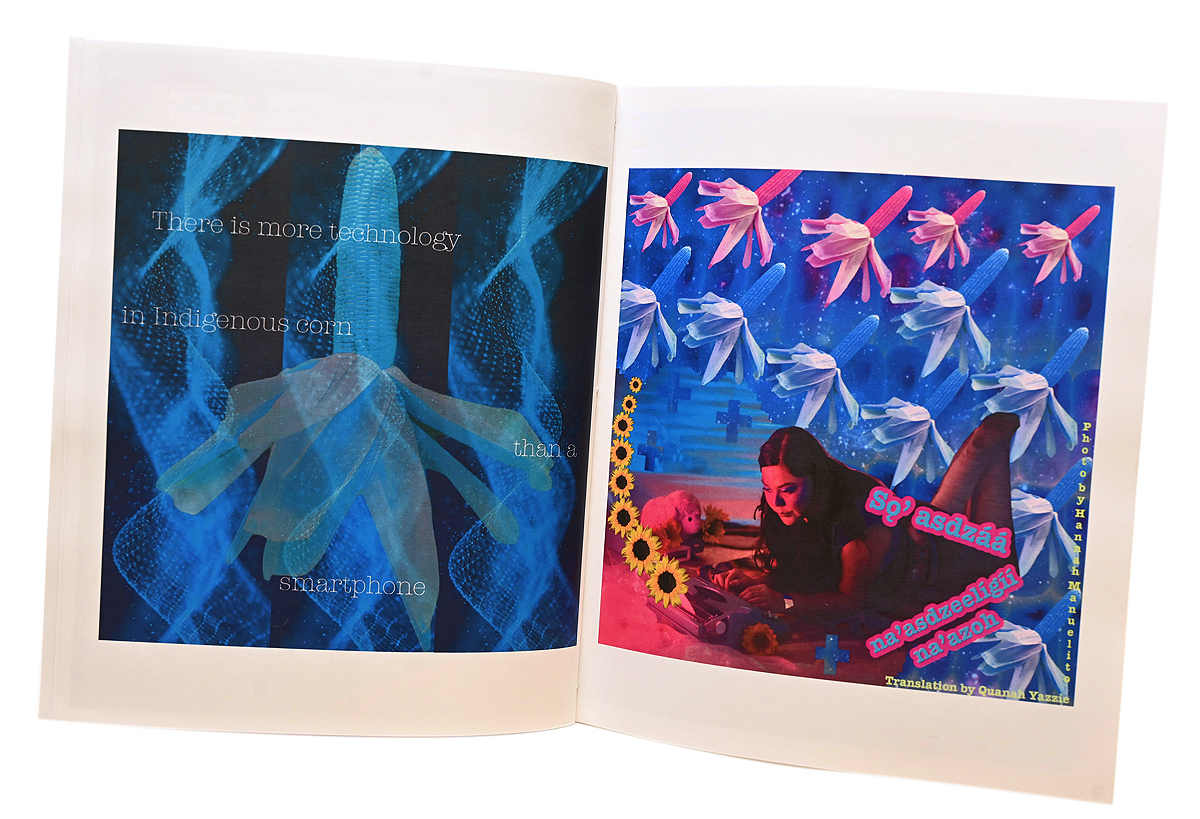

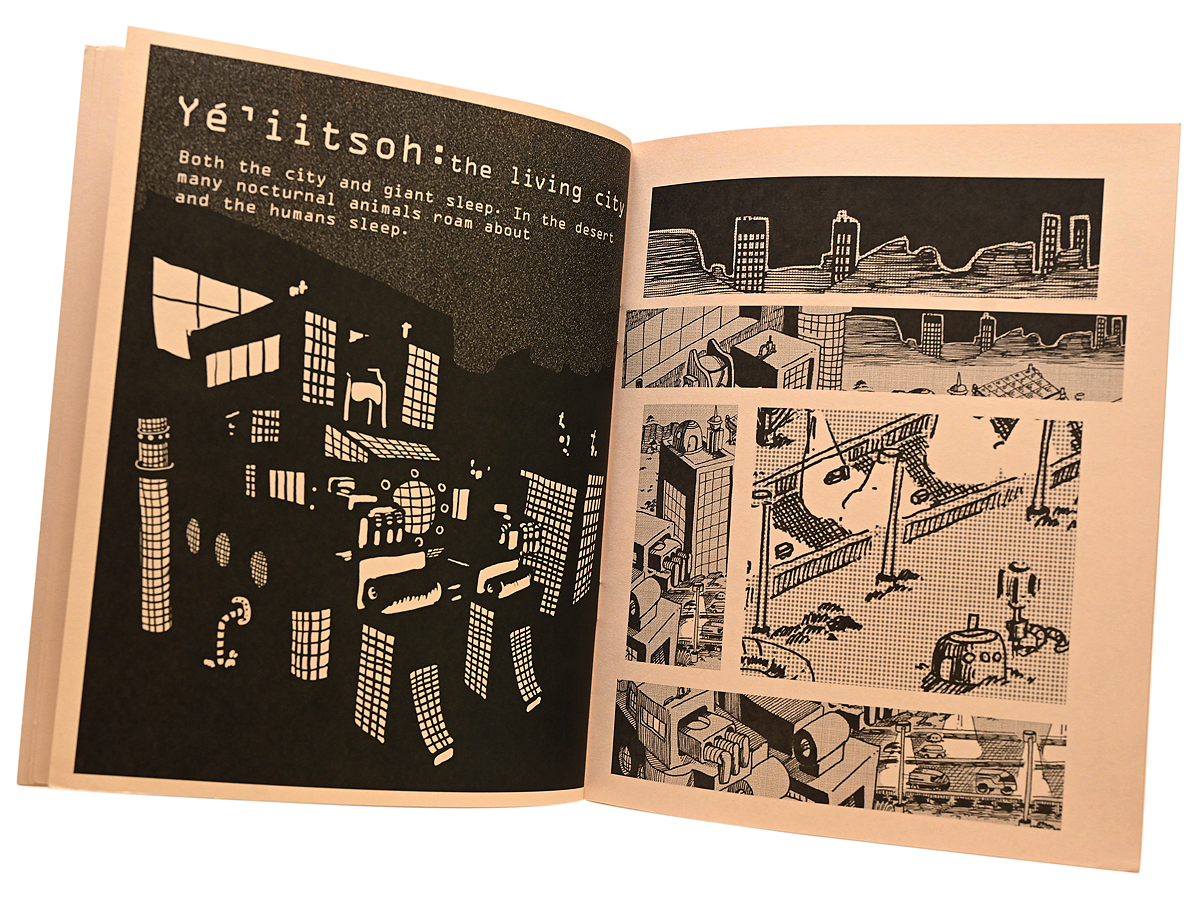

Historically, the lived experiences of Indigenous people have been represented narrowly and often inaccurately by outsiders. As a mission-statement plaque on the shelves reads, Fiveash’s collection attempts to rectify this by capturing Indigenous communities “as they live now, how they see themselves, and how they see their future.” A 2017 cookbook, Mino Wiisinidaa, compiles recipes for healthy traditional Anishinaabe foods (baked rabbit, wewaagagin soup, and hominy, to name a few) and advice from tribal members for harvesting and kitchen safety. Zines like Portals of Indigenous Futurism and Rez Bot rethink Indigenous pasts and envision limitless futures, integrating ancestral wisdom with elements like aliens and robots. Others, like Settler Sexuality, push the fluidity of gender and sexuality beyond Western conceptions, highlighting the intersectionality within Native identity that’s often sidelined in traditional archives.

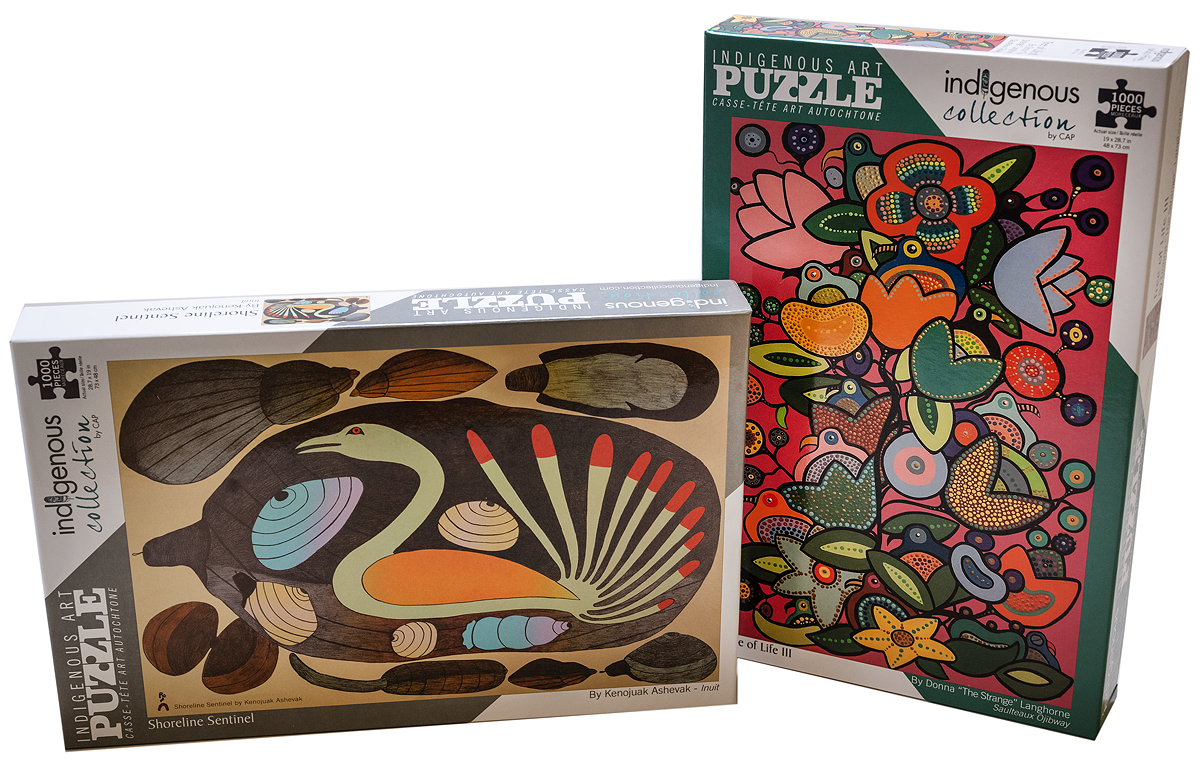

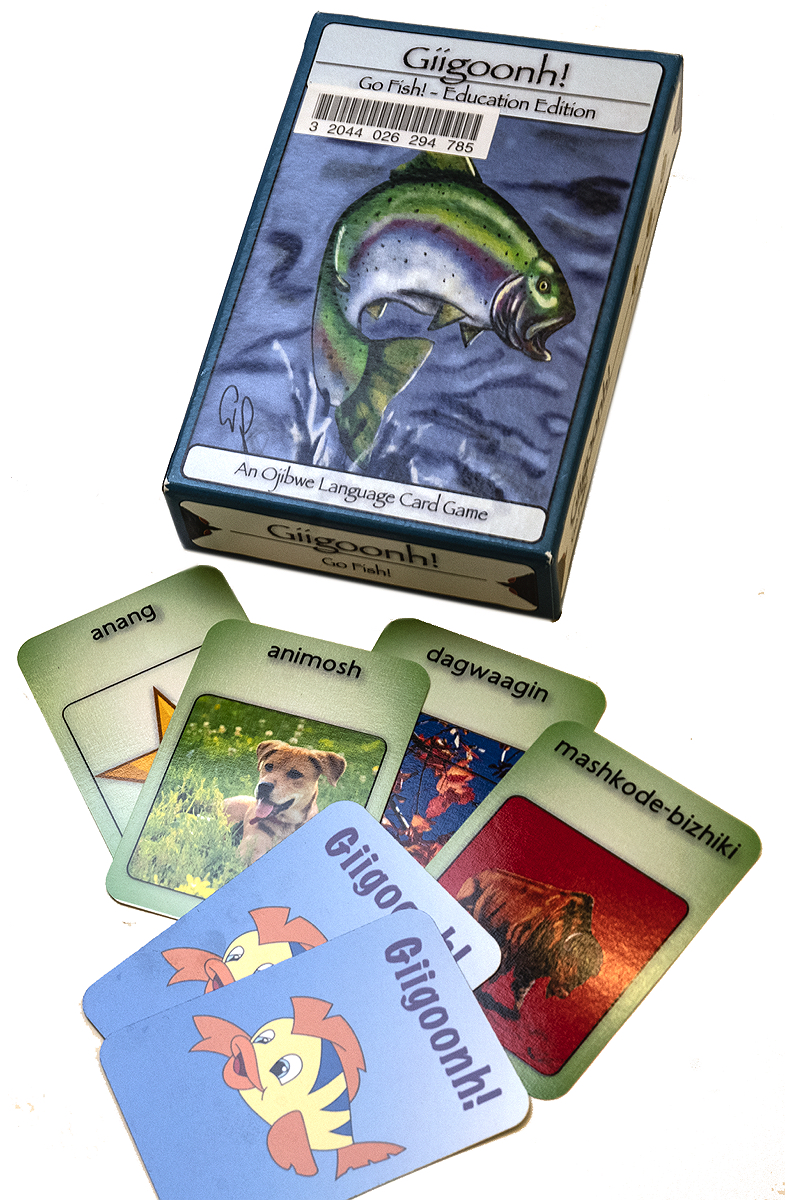

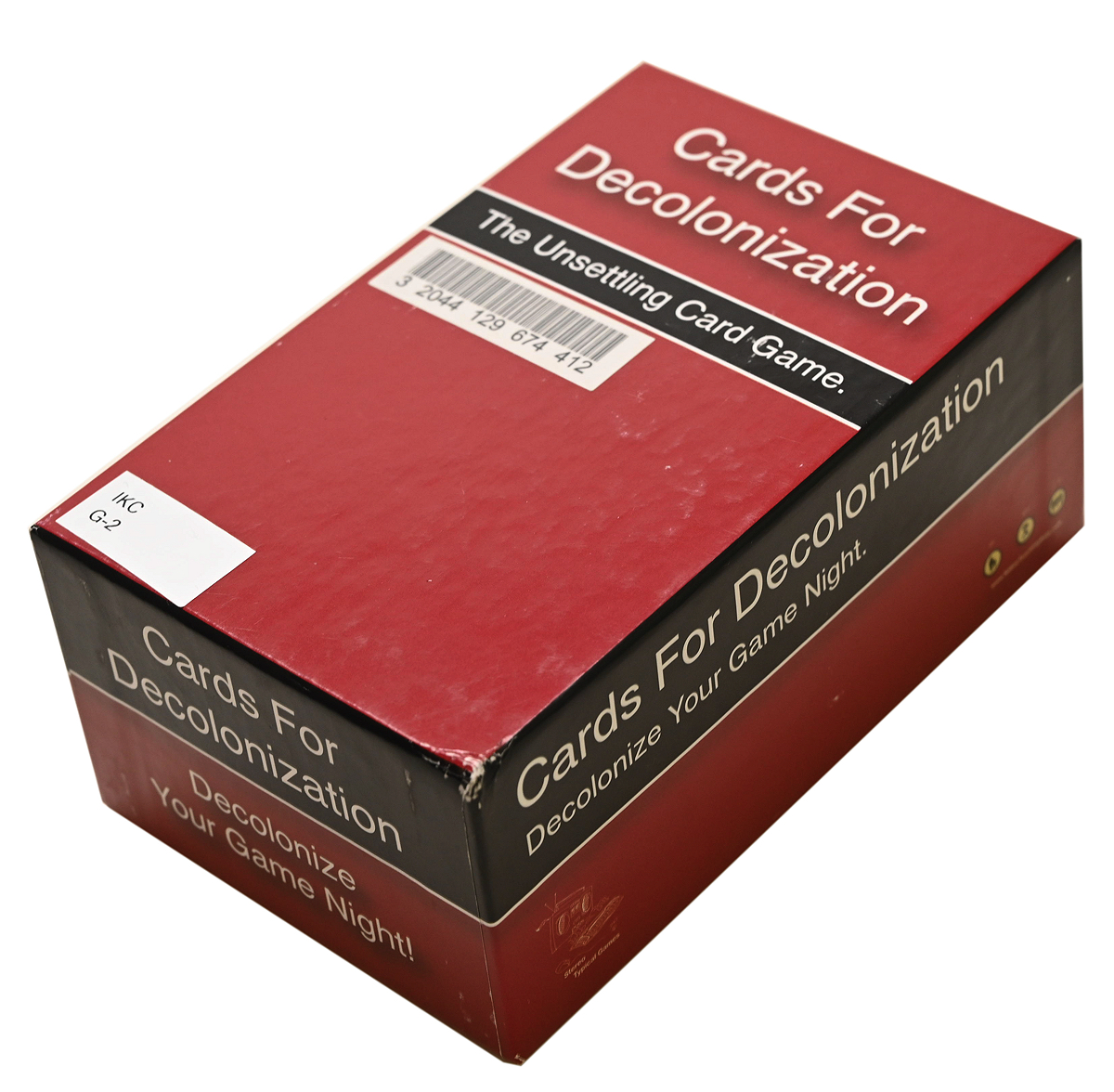

Many of the collection’s Indigenous-created or -inspired games resemble those found in mainstream American culture. But they also serve as catalysts for critical thinking. Inside an aquamarine box embossed with a shimmering green fish, “Giigoonh!” reimagines the classic “Go Fish,” immersing players in Ojibwe vocabulary as they make card pairs. A 2017 edition of “Spirit Island,” in which players work as spirits to drive invaders from an island, challenges the influence of settler colonialism in popular board games like “Settlers of Catan.” Fiveash points out a maroon set of “Cards for Decolonization,” a nod to “Cards Against Humanity.” “This is not for the faint-hearted of non-Indigenous people,” Fiveash remarks. “There’s a lot of jokes in there that would make white people uncomfortable.”

By hosting board game nights, soliciting community feedback, and offering a DIY zine shelf, the collection actively creates new knowledge and shares Indigeneity with new people. “I hope people find out that we’re very funny, creative, cool, and queer as Indigenous people,” Fiveash says. “You should be able to look at all these materials and feel like you have a deeper connection to Native people now—and not just from a textbook or an old movie you watched.”