Last fall, Syd Sanders ’24 got a campus job at Lamont Café. He attended unpaid trainings to prepare, and he received a draft schedule with the café’s available shifts. Then, in early November, his boss sent an email announcing that the café wouldn’t be opening that semester after all.

Since most campus jobs are posted and filled early in the semester, by the time he received the announcement, it was difficult to find another job. “It was pretty dire because, like many student workers, I’m trying to work because I need money,” Sanders says. “Not everyone here is rich.”

Sanders was able to explain his situation to the then-associate director of retail dining operations at Harvard and piece together work at other campus cafés and cafeterias. But “it was hard to find work,” he says, “and there was so much miscommunication.” He says that he wasn’t compensated for all the hours he worked at one of those other jobs—at a cafeteria on the Harvard Law School campus—even after he raised the issue with the associate director. And although he had counted on receiving income from that job during his last few weeks on campus, he says he was told after his last shift of the semester that students would not be staffing the cafeteria during reading period.

Frustrated by experiences like these, Sanders and a handful of other students began to talk about forming a union of non-academic student workers. They spent the last year walking through workplaces that employ undergraduates, such as libraries and cafés, asking students about workplace conditions. They petitioned the University for voluntary recognition; when Harvard denied that request in April, they garnered student support through a rally and outreach in dining halls. They also organized a campaign to get at least 30 percent of eligible employees to sign union authorization cards—the minimum percentage required by the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) to hold a union election.

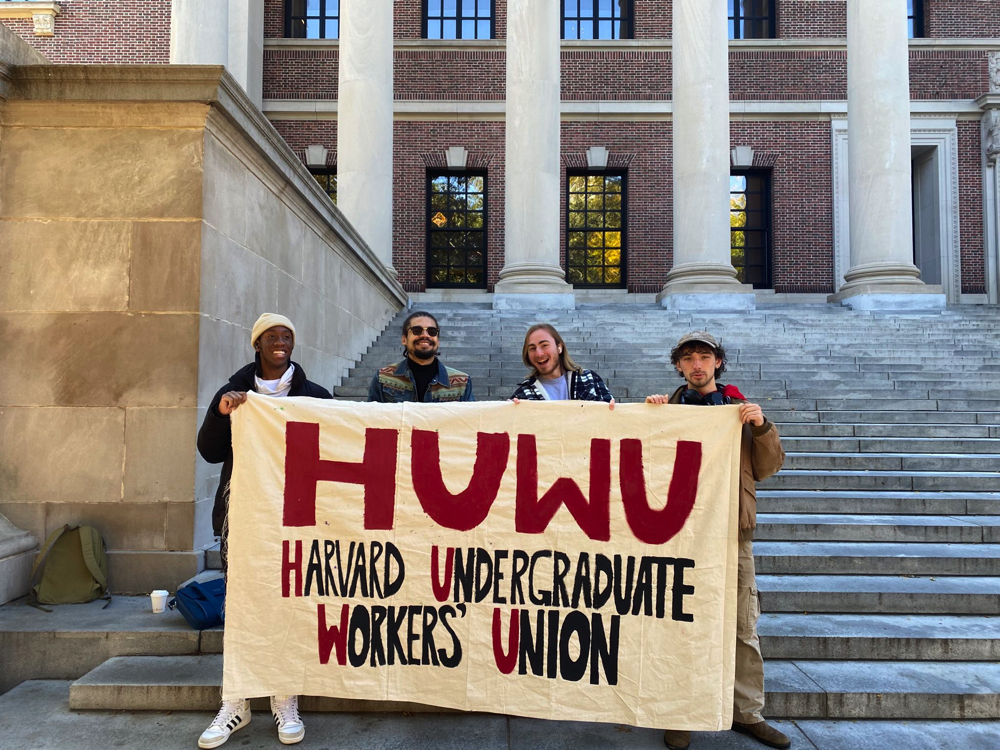

After a year of organizing, on October 25, non-academic student workers voted to unionize in a landslide election: 153 of 154 accepted votes were in favor. The NLRB certified the results on November 2. Members of the newly formed Harvard Undergraduate Workers Union-United Auto Workers (HUWU)—which is composed primarily of undergraduates, but also represents graduate students who hold non-academic campus jobs—say they hope the union will improve scheduling and hiring practices and increase wages, issues of particular importance to students who are working to help pay for living expenses and tuition.

“Sometimes, there’s this skewed perception of, ‘Oh, this is pocket money,’” says Olivia Pasquerella ’26, a HUWU organizer. “But for a lot of people, this is their living expenses in Cambridge, which is one of the most expensive places to live in this country. It’s so they can have a safety net when they leave college, so they can add to their savings or help parents back home.”

HUWU’s unionization takes place amid a larger burst of labor activism in workplaces—including universities—across the country. In 2018, Harvard graduate students made national headlines when they formed the Harvard Graduate Students Union-United Auto Workers (HGSU). Now, undergraduates are joining the wave: HUWU has become one of more than a dozen recognized unions composed primarily of undergraduates that have formed since 2017.

During the campaign, HUWU organizers sought advice from members of undergraduate unions from Kenyon and Grinnell Colleges. HGSU also provided mentorship and support, voting to affiliate with HUWU in March. As affiliates, the two unions share an executive committee—which manages union finances and strike authorization votes—but negotiate separate contracts with the University.

“The labor movement is built on the ethos of solidarity,” says HGSU president Evan MacKay, a J.D.-Ph.D. student in sociology and public policy. “So when we see these workers that are making wages that are not keeping up with inflation, and wages that are really a disservice to the labor they are doing for this institution… when we see them organizing against that, we want to be right alongside them.”

Some HGSU members were also concerned about non-union student employees working alongside unionized workers in settings like libraries and dining halls. “Harvard is a union-dense university, which is pretty unique,” says Koby Ljunggren, a Ph.D. candidate in biophysics and member of HGSU: various unions cover dining services workers, custodial workers, and clerical workers like faculty assistants.

“Union density is good,” Ljunggren says, but some union members worried that the University could save money by converting union jobs to nonunion student jobs, which pay lower wages. Union members can’t verify whether that conversion of jobs is actually happening, Ljunggren says—but unionizing non-academic student worker positions makes it impossible in any case. “That’s why I think unionizing these jobs is so important,” they continue. “We don’t want to create different tiers of workers within our own campus.”

Organizers plan to conduct a survey among HUWU members to determine bargaining demands. High among the priorities, they say, will likely be higher pay. The current minimum wage for undergraduates is $15 per hour; Sanders says he hopes that this will increase, and that wages will be tied to inflation.

Harvard spokesperson Jason Newton wrote in an emailed statement that the University looks forward to the collective bargaining process, “so that we can negotiate in good faith for a contract that will benefit our student workers and the University.”

Students also hope to have more input on hiring and scheduling practices for campus jobs. The current scheduling system, some say, makes it difficult for students—including those who are part of the federal work-study program, which helps students on financial aid fund the cost of their educations—to work as many hours as they would like.

Pasquerella is scheduled to work just two hours a week at their library job. Like Sanders, Pasquerella is able to “patch together” other jobs to increase the amount they work. But during workplace walkthroughs, they heard from other students whose workplaces had more transparent and equitable scheduling systems. “That’s the reason why we’re unionizing, because there are some workplaces with these practices that workers love, and that make their lives easier and smoother,” Pasquerella says. “And we’d like to standardize that across jobs.” Students who work at cafés and the Cambridge Queen’s Head Pub, a campus social space that serves alcohol, also hope to gain the option to receive credit card tips.

Not every yes vote to form the union was cast by workers who were closely involved in union organizing. “Being an undergraduate worker at Harvard, it’s a pretty good gig,” says Sam Trottier ’24, who works two campus jobs—one at a library, the other at the Quincy Grille. “But certainly, things have been getting more expensive, and I wouldn’t mind the raise.” Unionization could also help incorporate student perspectives into employment practices beyond scheduling and hiring. For example, Trottier says, during grille shifts, “A lot of times, you have to stay to clean up or get there early and you don’t get paid for that time, which I would like to see change.”

Some students hope unionization will establish third-party arbitration for claims of sexual harassment and discrimination in the workplace. HGSU has long petitioned the University for third-party arbitration, thus far unsuccessfully. “I hope the University hears this out this time around in bargaining,” Ljunggren says. Third-party arbitration, as opposed to internal arbitration, is important because “If the University disagrees [the incident] took place, or disagrees with any of the remedies, we can take that to a third party who will issue a binding decision on what must be done to make sure the worker is safe,” they add.

As the union prepares to bargain with the University, organizers also plan to expand HUWU’s size. The 154 accepted votes don’t represent the full range of non-academic student workers: the total bargaining unit includes at least 400 students, 320 of whom were eligible to vote under the requirement that students work at least 20 hours in the five weeks preceding October 7. Union members currently include workers in University libraries, cafés, and equity, diversity, and inclusion offices. Organizers plan to submit to the NLRB a petition for an Armour-Globe election, which would extend membership to students employed in other jobs around the University, such as tour guides and students working in University centers.

Sanders says the union hopes to start bargaining this semester or next—in part because many organizers like himself are graduating in the spring. “We’ve been working hard on this, so we want to get to the bargaining table before we graduate,” he says. “We really want to get going, and I think that we can.”