The Sentinel State: Surveillance and the Survival of Dictatorship in China, by Minxin Pei, Ph.D. ’91 (Harvard, $35). A professor of government at Claremont McKenna details the technology (cameras, AI facial recognition, and phone tracking) and enormous human resources the Chinese Communist Party has devoted to domestic spying. The Orwellian system of “preventive repression” meticulously documented here helps explain why the economic liberalization of the People’s Republic has not been accompanied by comparable political change.

All in Her Head: The Truth and Lies Early Medicine Taught Us about Women’s Bodies and Why It Matters Today, by Elizabeth Comen ’00, M.D. ’04 (Harper Wave, $32). An undergraduate historian of science turned oncologist (at Memorial Sloan Kettering) presents a serious, ambitious survey and analysis of why “Western medical storytelling has largely eschewed the discussion of women’s bodies, let alone elevated them as powerful, capable, or of equal worth to men’s.” She is clear-eyed about the consequences for understanding women’s “pain, pleasure, strength, and intellectual capacity,” and for addressing women’s health and well-being.

An Arrow’s Arc: Journey of a Physician-Scientist, by Carl Nathan ’67, M.D. ’71 (Paul Dry Books, $19.95 paper). The chair of microbiology and immunology at Weill Cornell Medicine explains his path toward a much-honored career researching diseases like tuberculosis and malaria. His stories are vivid. As a nine-year-old felled by asthma, he was revived by a timely injection of epinephrine: “Relief was almost instant. The asthma organ stopped piping. In the darkened bedroom, my mother’s face became the sun”—an early lesson in effective therapy. And when he was a Yale oncology fellow, a dying patient told him, “You doctors worked hard to help me, but you failed, didn’t you?…Don’t just keep doing what you do. Make it better.” Beneficiaries

of medical science could not find a better introduction to the impulses that propel it.

Liberty Equality Fashion: The Women Who Styled the French Revolution, by Anne Higonnet ’80, RI ’20 (W.W. Norton, $35). The Olin professor of art history at Barnard recounts the brief upheaval in women’s wear spurred by the French Revolution, through the stories of Joséphine Bonaparte, Térézia Tallien, and Juliette Récamier. Térézia, stripped naked by jailors in a sordid cell, had previously been imprisoned (per Higonnet’s list) by stays, petticoats, three-piece gowns, silk brocades, massive skirts, lace, baubles, and “towering coiffures.” Having narrowly escaped the guillotine, she would “decapitate aristocratic style.” As she emerged transformed, “No one had ever imagined a woman could wear so little and look so gorgeous.”

The Making of Lawyers’ Careers, by seven authors, including David B. Wilkins, Kissel professor of law, and Meghan Dawe, fellow at the Law School’s Center on the Legal Profession (University of Chicago, $35 paper). A scholarly examination of “inequality and opportunity in the American legal profession” (the subtitle) and the “large-scale social structures” (such as gender, race, class, and law school status) that shape such work. The authors find persistent inequalities throughout the profession—divisions that “widen over the course of careers.” The selectivity of the law school attended influences where J.D.s begin practice, which then “heavily shapes” their subsequent trajectory. “Thus, policies regarding law school admissions are critical” to inequalities in the profession—a challenge to firms’ insufficient diversity efforts in a post-affirmative action era.

Deals: The Economic Structure of Business Transactions, by Michael Klausner and Guhan Subramanian (Harvard, $24.95). Professors of law and business at, respectively, Stanford and Harvard, demystify deals—mergers, licenses, hiring talent—by examining cases (Microsoft’s merger-purchase of LinkedIn, for instance) to illuminate the principles of “creating value through an exchange.”

A succinct professional primer, but also, one suspects, a guide for laypeople who wonder what goes on in such transactions every day, at such great expense, with such enormous fees (and to what end).

All We Were Promised, by Ashton Lattimore ’08, J.D. ’13 (Ballantine, $30). This debut novel, a sweeping historical fiction set in the late 1830s, captures Philadelphia’s status as home to the largest free black population in the country—but also as the site of ferocious anti-abolitionist riots. The centerpiece is the creation of Pennsylvania Hall as a venue for antislavery and other reform lecturers—and its destruction by arson four days later.

Your Money or Your Life: Debt Collection in American Medicine, by Luke Messac ’08 (Oxford, $27.95). An M.D.-Ph.D., the author is an emergency medicine physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and a historian who studies the political economy of healthcare. As a scholar, he is animated by passion: “When I questioned my own hospital’s use of lawsuits to collect debts from poor patients, I was not a favorite among C-suite executives, but I had the steadfast support and guidance of my fellow residents, mentors, and program directors, who I am pretty sure do not want to be mentioned by name.” His review of debt collection contributes to a wider view of the state of care: “No one has fated hospitals in America to be palaces of plunder; they can be houses of healing.”

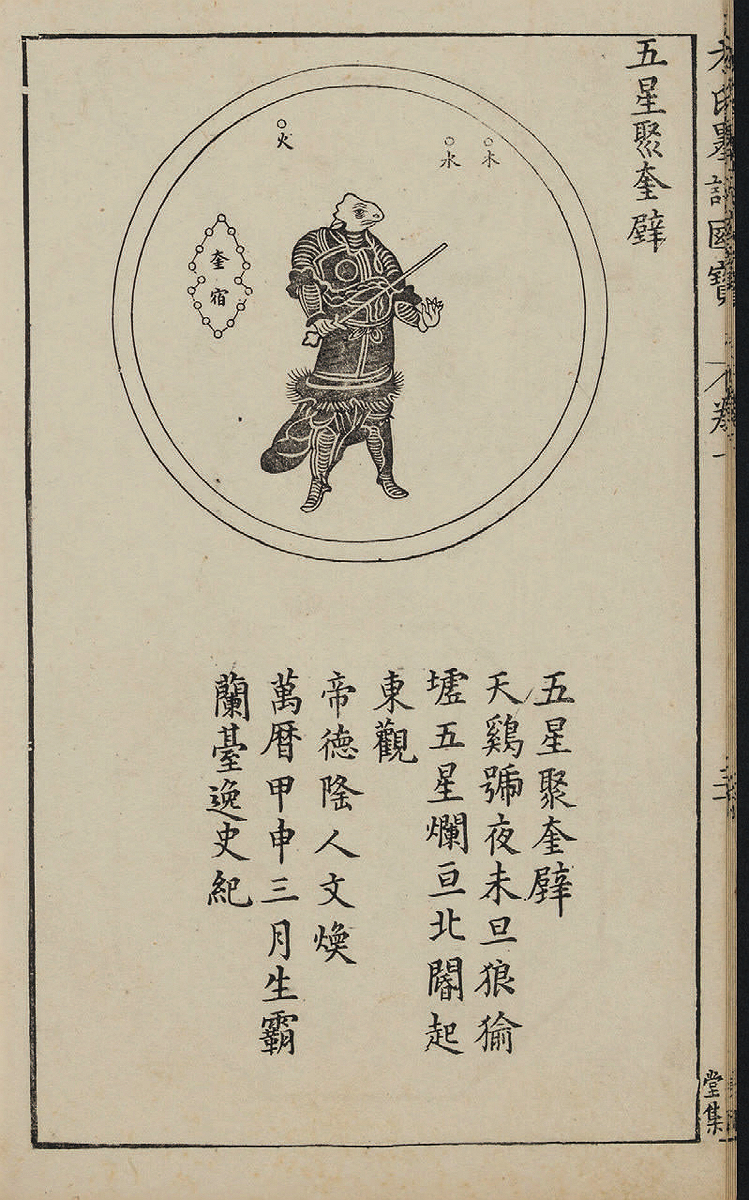

The Inscriptions of Things: Writing and Materiality in Early Modern China, by Thomas P. Kelly, (Columbia University Press, $35 paper). Chinese literature has long been acknowledged as a peak human accomplishment. But the author, assistant professor of East Asian languages and civilizations, establishes in this scholarly analysis just how much important Chinese writing exists as inscriptions on cups, stone, ink slabs, and other objects and in other forms. This is a specialist’s book, but one that reminds anyone who has beheld such objects in a museum of the sheer depth and breadth of such writing, and the civilization in which it was done, a half-millennium and more ago.

“Whatever It Is, I’m Against It”: Resistance to Change in Higher Education, by Brian Rosenberg, visiting professor and president in residence, Harvard Graduate School of Education (Harvard Education Press, $38 paper). An English literature scholar who served as Macalester College’s president from 2003 to 2020 details why change comes so hard within “classic and privileged” colleges and universities. Much as he believes in “the transformative power of higher education,” he laments that the industry “just cannot seem to change or transform itself in ways beyond the incremental” in the classroom and beyond. A book-length explanation of ideas treated in brief in “Is Harvard Complacent?” (September-October 2021, page 47), it is full of telling stories about the academy—refreshingly, motivated by concern to improve rather than to trash its leading institutions and their performance of their core mission.

How the Harvard Business School Changed the Way We View Organizations, by Jay W. Lorsch, Kirstein professor of human relations emeritus (Business Expert Press, $28.99 paper). In a memoir-cum-argument, a longtime leader in understanding organizational behavior and leadership, and in case teaching, summons the Business School back to its pedagogical roots—a human-centered model of listening, observing, and testing—and away from the newer sirens of economic modeling, game theory, and data science.

Sleep Well, Take Risks, Squish the Peas, by Hasan Merali, M.D. ’10 (Health Communications Inc., $17.95 paper). Want to live your life better? The author, a physician-researcher, points to “the beautiful world of the toddler mind…a world filled with wonder, excitement, and true happiness. A place where there is complete honesty, unflappable empathy, little judgment based on your appearance, a drive to be active and eat appropriately, and where your ideas and what you are willing to try are endless.” In this telling (balanced, of course, by the downsides), understanding the toddlerverse is a point of entry into a marvelous stage of children’s lives and a more positive way of being an adult.