All summer long, an oyster farm and raw bar on Duxbury Bay has been the site of a public art installation that offers a playful homage to the Commonwealth’s rural coast and history of ocean farming. Created by two Harvard architecture students, “Oyster Floats: Camera Obscuras for a Floating City,” consists of five small brass sculptures whose shapes mimic the floating sheds that have become an increasingly common sight in the waters off New England as the oyster-farming industry has ballooned. “These are essentially Home Depot sheds that are sitting on these flat barges, and that’s where the farmers sort and cull the oysters” that they haul up from the seabed, says Randy Crandon, M.Arch. ’25, a Duxbury native and the son of a sailor who has worked part-time on oyster farms and spent much of his life on the water.

“Oyster Floats” debuted this spring at Harvard’s Arts First festival, and was remounted in June by Island Creek Oysters, which operates a farm and restaurants in Duxbury. The installation will remain in place through the end of oyster season in September.

For both Crandon his artistic collaborator Dylan Herrmann-Holt, M.Arch. ’25, the ordinariness of the oyster sheds was part of the inspiration. “They’re working structures,” says Herrmann-Holt, “these kind of weird, vernacular objects.” Raised in rural Ohio near the Kentucky border, he grew up fascinated by barns—their shapes and symmetries and disparate uses—and spent time working with Habitat for Humanity, helping to frame new houses. “My grandpa was a plumber and pipefitter,” he says, “and my whole life I’ve been around these very technical, construction-related things. In rural Appalachia, when we needed to fix the barn, we just went to Lowe’s and got the stuff to fix it, and I think that’s part of the reason why I’m interested in common materials and everyday people as designers. Everyday people do interesting things all the time.”

And yet, sometimes an unexpected transcendent beauty emerges. The floating sheds that oyster farmers use “are very adaptive to their environment,” Crandon says. “When the winds and the tides shift, they’ll all sort of rotate together. It’s like watching a flock of birds fly in unison.” He pauses for a beat, considering. “It’s just like a piece of architecture.” Part of the intention in creating the artwork, he and Herrmann-Holt say, was to remind city dwellers of their connection to the marine world. “Here in Cambridge, we have the Charles, but people don’t really get to the ocean very often,” Herrmann-Holt says. In the summer, he teaches course on the history of Boston, and the region’s aquaculture is a major topic: “One of the reasons why Boston became a city is because of this ability to farm things on the water.”

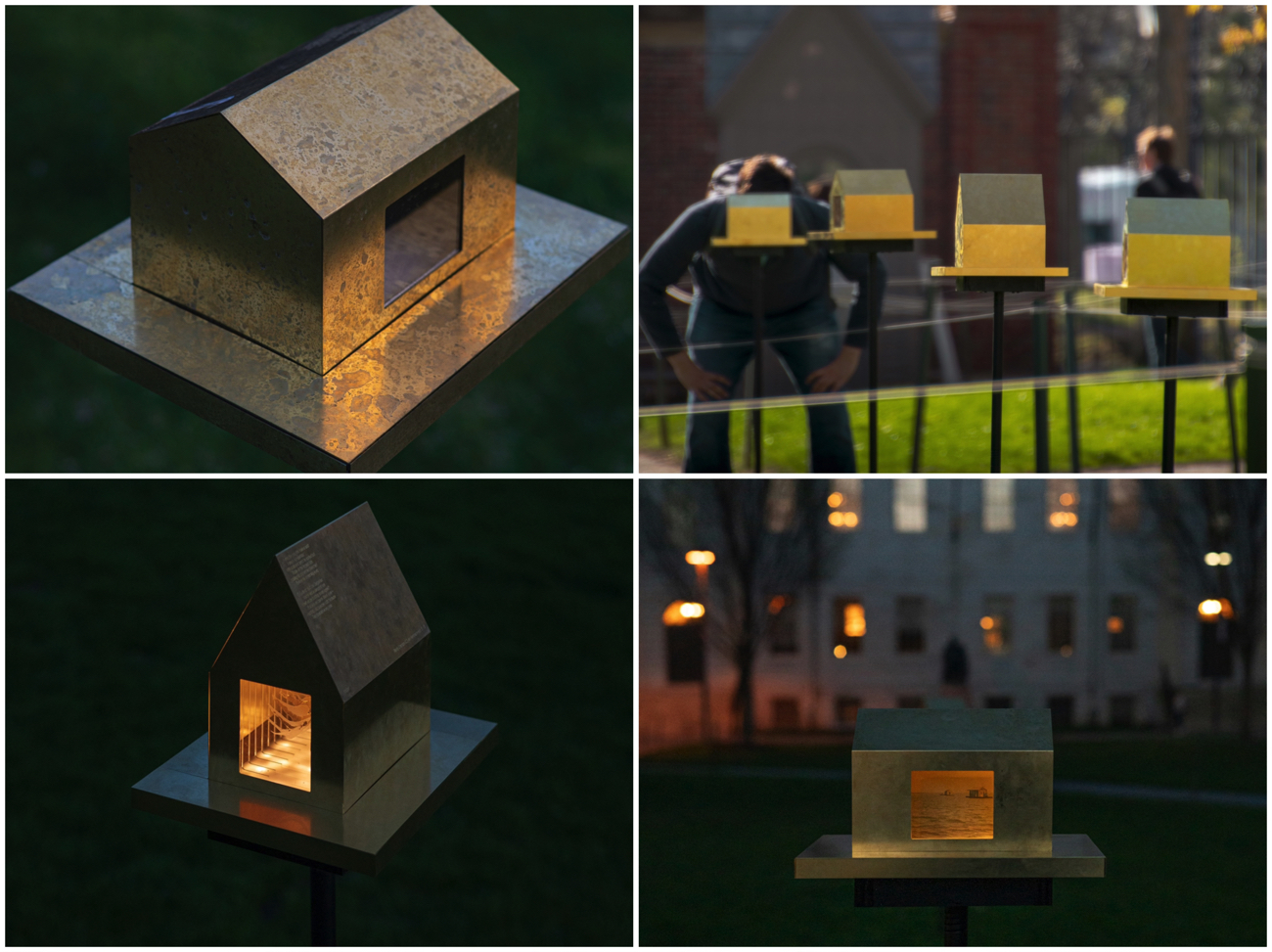

The playfulness of “Oyster Floats,” comes out most vividly in the way Crandon and Herrmann-Holt reinterpret the sheds their artwork is modeled after. The two created the sculptures themselves at the Graduate School of Design’s fabrication lab (a process that required many prototypes and some trial and error). It might seem highfalutin to choose brass as the material for artwork inspired by a commonplace object, but it’s not, really: Crandon points out the long history of using brass for many boat fittings and hardware. Plus, the artists wanted a material that would show wear in a way that heightened the connection to the real-world structures. “When we first put them out there, they were these very pristine, golden-looking little houses,” Herrmann-Holt says of the artwork. “But then, because brass patinas and weathers so quickly, with the rain and the birds, they’ve really changed. That’s why we really liked brass over another material: it starts as something very precious, but quickly becomes something that is of the environment.”

The artists also made the installation interactive: each sculpture is suspended on a four-foot pole (so adults will have to bend down to see them) and includes openings though which viewers can peek inside at photographs (taken by Crandon) of oyster-farming and New England fishing towns. Engraved on the roofs are stanzas from Lewis Carroll’s “The Walrus and the Carpenter,” a children’s rhyme in which the walrus and carpenter persuade a group of oysters to walk home with them for dinner—only, the oysters are the dinner. The poem is silly and absurd, but with a sinister edge: “‘O Oysters,’ said the Carpenter, / You've had a pleasant run! / Shall we be trotting home again?’ But answer came there none— / And this was scarcely odd, because / They'd eaten every one.”

| PHOTOGRAPHS BY RANDY CRANDON

In the installation, the artists placed the sculptures (which are numbered) out of order, another nod to the random ad-hoc-ness of working structures, but also a way to encourage viewers to wander “through and around” the installation, Herrmann-Holt says. “The placement resembles how people would mill their way through, says, a cluster of objects, as opposed to a single big object.”

Like the real oyster sheds clustered out in the bay. Or the oysters in the oyster beds below.

“Oyster Floats” is on display at The Raw Bar at Island Creek Oyster Farm, 403-7 Washington Street, Duxbury, Massachusetts. The installation will be in place through the end of oyster season.