The photographer Ansel Adams is best known for his legendary black-and-white landscapes of the American West: clouds billowing across the Sonoma Mountains, a gibbous moon hanging low over Half Dome in Yosemite. But in a 1964 snapshot, an unfamiliar subject appears in front of Adams’s camera: himself. He gazes wide-eyed at the lens, mouth ajar in a slight smile, tree branches behind him appearing to sprout from his head like horns.

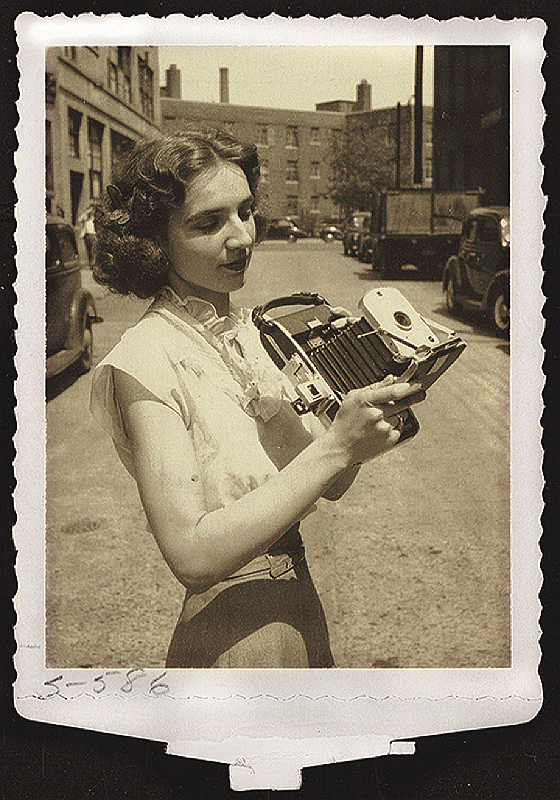

The photograph is one of thousands taken by Adams as a consultant for the Polaroid Corporation, advising on prototype cameras and film. Thirty-three of these “test photographs”—along with dozens of images by other photographers and company correspondence—are on display at Harvard Business School’s Baker Library until mid-April as part of an exhibit on Meroë Morse, manager of Polaroid’s black-and-white photographic research from 1955 to 1969.

Morse’s path to that role was unconventional. She studied art history at Smith College and joined Polaroid in 1945, just after graduation, with no background in science or business. She came recommended by Clarence Kennedy, Ph.D. ’24, a Smith art history professor who had corresponded for years with Polaroid founder Edwin H. Land ’30, S.D. ’57, about photography’s artistic potential.

Morse served as the principal liaison to Adams and other art photographers who consulted for the company. In 1948, Polaroid researchers released Type 40 sepia film. The following year, Adams used the film to take a picture of a burial ground in Concord, Massachusetts, sending Morse the print along with a critique of its limited tonal range. In response, the lab developed higher-contrast black-and-white film, which Adams praised as “beautiful in quality.” (The film came with a new challenge, however: it discolored quickly. To remedy this, Morse’s team created a chemical solution sold in a tube, also displayed at Baker. Users coated images in the solution, then shook them to dry, giving rise to a ritual that persisted even after film improved and the coating was no longer needed.)

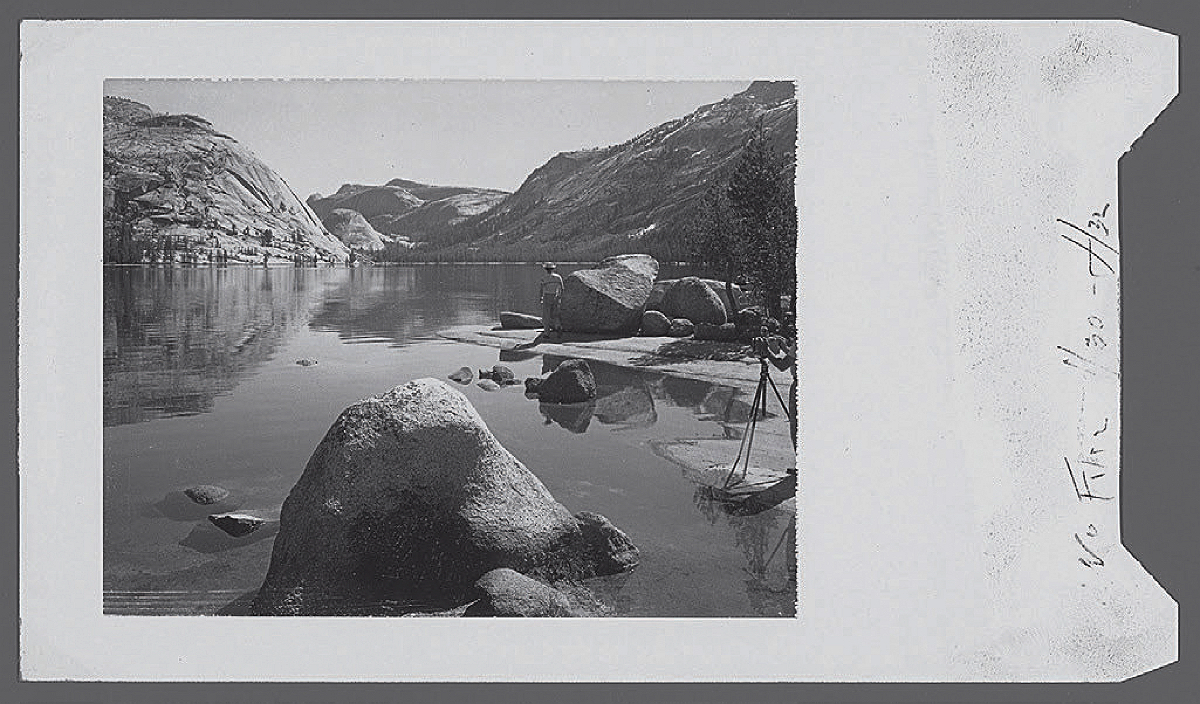

Adams would continue to use Polaroid cameras to photograph landscapes, still lifes, and people ranging from Land to Georgia O’Keeffe. He provided feedback to Morse in letters; in one, he noted that a camera’s exposure was insufficient for capturing the high-contrast landscape of Yosemite or the details in a tangle of roots. “It is unfortunate that so many photographers have thought of the Land camera as a ‘toy,’ a casual device for ‘fun’ pictures,” Adams wrote in a 1963 manual on Polaroid photography. Indeed, the device was a central part of his artistic practice—more democratic and spontaneous than traditional cameras, even occasionally lending itself to a twentieth-century selfie. Morse’s ability to translate his creative insights into scientific advancements perhaps offers a lesson for today’s tech companies: consider hiring an art history major.