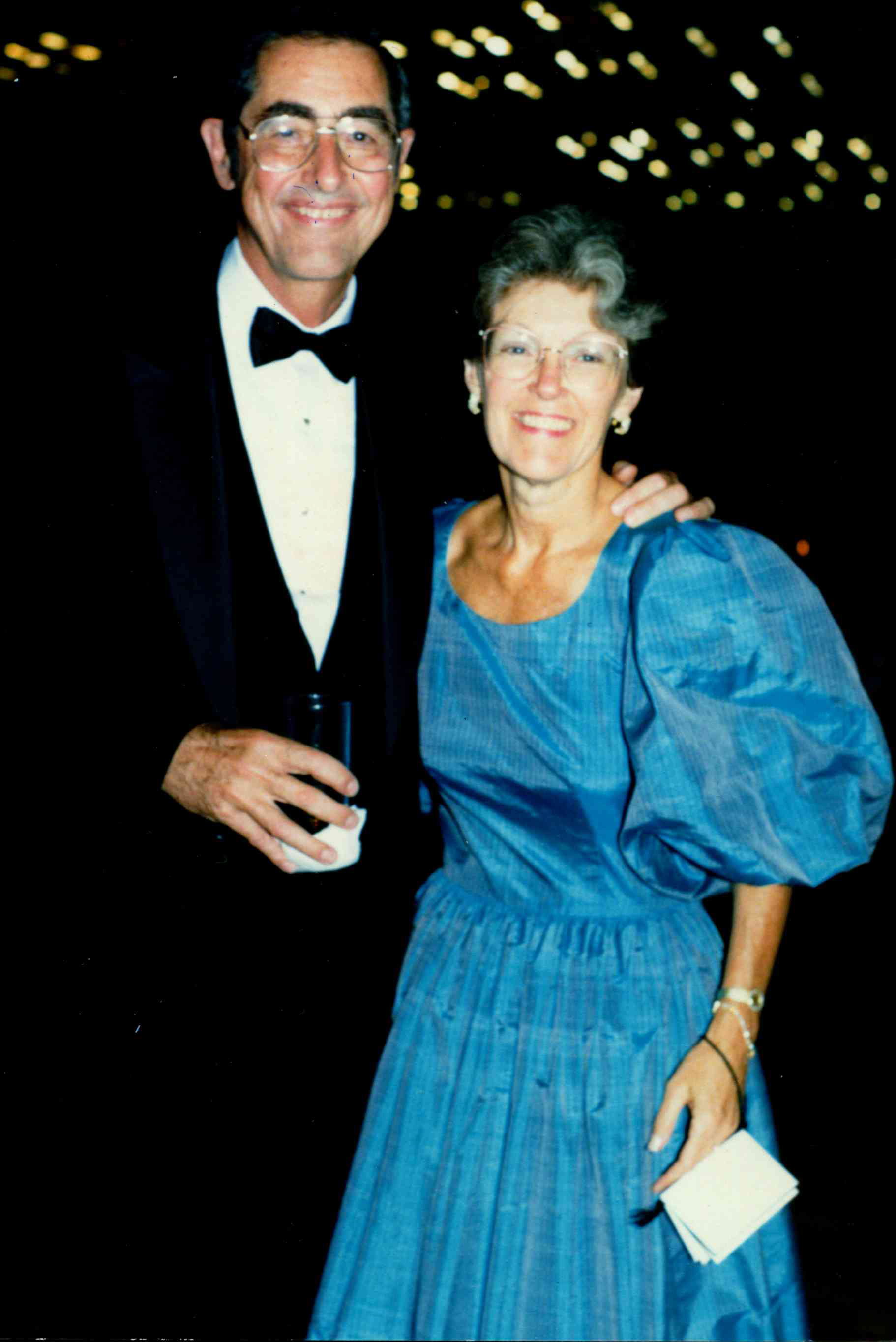

For the DeSanctis family, medicine had always been a way of life. Roman DeSanctis, M.D. ’55, was a renowned—and busy—cardiologist, and for his wife, Ruth, and four daughters, that often meant celebrating birthdays early in the morning, so that he could participate. Hospital fellows and residents were frequent dinner guests, and patients often became family friends. Decades later, when Ruth developed Alzheimer’s disease, her care became a part of the family’s life together, too, especially for DeSanctis and his daughter Lydia, who were her primary caregivers. Their experience led to the founding of the dementia caregiver support program at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH).

To the outside world, Roman DeSanctis, who died last July at 93, was best known as a physician and teacher. A gifted diagnostician, he could hear heart murmurs that others overlooked and see diseases in basic X-rays. For 59 years, he practiced at MGH, where his patients included John Wayne, Henry Kissinger ’50, Ph.D. ’54, L ’55, and Boston Celtics coach Red Auerbach. King Hassan II of Morocco would call whenever he fell ill; there’s a story about a truckful of Moroccan rugs arriving at DeSanctis’s home one day as a surprise thank-you for the doctor’s care.

A Harvard Medical School (HMS) faculty member since the 1960s, DeSanctis mentored generations of students, emphasizing the humanistic side of medicine: kindness, compassion, the careful work of listening. “Cherish your patients,” he told the school’s graduating class in a 2014 lecture. “We should never forget that the beauty and essence of medicine still lies in the highly personal and precious interactions between ourselves and the patients we serve.”

But DeSanctis’s more private role as caregiver to his wife profoundly affected him, and in 2015, at his urging—and with funding he helped secure—MGH launched a support program for dementia caregivers. Now part of the Dementia Care Collaborative (DCC), the program includes education, skills training, and support groups for caregivers. During his wife’s Illness, DeSanctis’s children say, it was a support group that helped save him.

Ruth first started showing signs of Alzheimer’s in the 2000s, when she was in her late 70s. The couple had first met in 1955, when he arrived at MGH as a medical resident; she was working there a nursing instructor. “They had such a strong partnership,” says their daughter Ellen DeSanctis. When Ruth developed dementia, it shook him, despite his many years in medicine. “He was this very competent, widely recognized physician,” she says. “Then all of a sudden, his wife comes down with an incurable disease, and one that doesn’t go quickly, one that drags everybody in their life down with it. And my dad, who’s been around death and dying, who all his life has been a healer—suddenly, it was like, what do you do? He found himself at a loss. The whole family did.”

DeSanctis leaned on support from MGH colleagues, especially social worker Barbara Moscowitz, founder and associate director of the DCC’s education and support program (a role that involves coordinating and leading support groups); and Vicki Jackson, chief of palliative care and geriatric medicine.

Through the Alzheimer’s Association, DeSanctis joined a support group for men whose wives were suffering from the disease. “That was a big deal for him,” Ellen says. “He was this prominent doctor, but he was also just one of the guys who showed up in a meeting place with other people and told and shared stories about their experience.”

“It was just a room full of really smart, interested, kind-hearted men, who were all dealing with spouses at different stages of dementia—and, really, dealing with the unknown,” remembers her sister Lydia. In 2012, as her mother’s condition began to deteriorate more rapidly, Lydia moved home to Massachusetts from Bogotá, Colombia, where she’d been working as a translator and editor. For three years, she lived in the family’s home in Winchester as a full-time caregiver, sharing that responsibility with her father, who retired from clinical practice in 2014, a change that allowed him to spend more time with his wife. (He still worked part time, as a fundraiser with the MGH development office.)

Lydia describes those years of caring for her mother as almost transcendent, a harrowing and impossibly difficult period, but also full of love, and, at times, even beauty. When she was a teenager, she and her mother had had a stormy relationship, but by the time Ruth got sick, the two had long since reconciled and became close. “It was a good foundation for caregiving,” says Lydia, and an essential one: early on, as her mother grew increasingly irrational and unpredictable—even hostile—“I realized,” she says, “that I couldn’t need anything more from her.…I had to be good with what I had with her and go from there.” She came to understand caregiving as an emotional practice as much as a physical one.

“There’s a really intense intimacy that goes with taking care of somebody who’s that vulnerable,” she says. For the children of people with dementia especially, this can come as a shock, “being that up close and personal with what they see in their parents’ behavior.”

Her father, too, came to a deeper understanding of the emotional side of caregiving, Lydia says. He joined the support group after retiring from practice, when he was at home more, and taking on more of the caregiving. “It was clear that Dad needed some help,” she recalls. By then, she had been attending a support group at a nearby community center for a while. She invited him to a meeting, “just to get some perspective on what this is like and what we might have to face together.” Eventually, the two found a separate, all-male group, where DeSanctis felt more comfortable. “It was really nice to see him benefit from that,” she says. “It made such a difference.”

The end of the family’s caregiving came suddenly, in early February 2015, during a week when Roman DeSanctis was out of town on a fundraising trip. A nor’easter blew in that Monday, and Ruth and Lydia watched the snow fall for hours. “I had one of the best days I ever had with Mom, just getting snowed in together,” Lydia says. The next morning, she came downstairs and found her mother sprawled on the floor: alert but confused and clearly terrified. It wasn’t clear what had happened, whether she’d fallen or suffered an attack. An ambulance arrived, and Ruth DeSanctis left home for what turned out to be the last time. She spent a month in the hospital; afterward, it was clear she needed 24-hour professional care. The family moved her to a facility not far away, where Ruth lived for three more years. She died in March 2018, at age 87, during another snowstorm. Roman and Lydia DeSanctis, along with most of the rest of the family, were at her bedside.

“Going through dementia care, it changes you,” says Ellen DeSanctis. Certainly it changed her father. “He developed a really strong sense that these were better angels, these people who work in dementia care and who work with caregivers. I think he knew he couldn’t have made it without them—without his men’s group and the support of people at MGH.” Launching the hospital’s caregiver support program was part of that recognition. “He knew immediately that this was an underfunded, underappreciated, under-recognized, even under-resourced aspect of medicine,” Ellen says. “And that it was an aspect that needs attention.”