Tours of the Museum of Printing, in Haverhill, Massachusetts, begin, naturally, with Johannes Gutenberg. A replica of the German inventor’s fifteenth-century Bible is open for perusal among displays of more than a hundred other Good Books—almost all collected by museum president Frank Romano. There’s one in Braille, others in “Pirate Speak” and phonetic shorthand, along with a framed leaf of the Eliot Indian Bible, the first translated into an American indigenous language, printed at Harvard in the mid 1600s. He's still hankering to fill holes in his collection, and ultimately wants a copy of every Bible printed in English.

Not that he needs more stuff. Romano’s almost 50-year-old museum is run by volunteers and housed in a nondescript 30,000-square-foot building packed, conservatively, with close to two million items. That includes another 11,000 books, vintage letterpresses, stone lithography and offset and phototypesetting equipment, typewriters, and an original Xerox machine. “Every different printing method is here,” Romano says—including one of only 50 working linotype machines in the country. That revolutionary invention, introduced in the 1880s, mechanically lays out a line of metal type, doing the work of a host of hand-typesetters. This panoply reflects the museum’s mission: to preserve and show the technical development of modern graphic arts in America, with a focus on printing and typesetting from Gutenberg through Steve Jobs. “We want people to realize the importance of history,” says Romano, “because the technology of printed matter changes everything.”

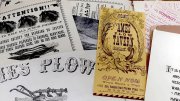

Affectionately known as MoP, the Haverhill nonprofit is one of three major museums in the nation highlighting aspects of printing, but it boasts the world’s largest eclectic collections of hardware, artifacts, paper materials, and ephemera. Its letterpresses, for example, demonstrate how, for centuries, inked lettering was pressed directly on paper, with workers hand-composing each line using individual metal or wooden letters. The Industrial Revolution helped usher in lithography and linotype; the latter (also invented by a German, Ottmar Mergenthaler) was used by newspapers and magazines well into the twentieth century. MoP artifacts include the metal typeface composing board and cardboard mold from the last day in 1978 that the New York Times was printed using the hot-metal type method on linotype machines. The worthwhile documentary Farewell, Etaoin Shrdlu chronicles that event and loops for museum visitors.

Among MoP’s letterpresses, the cast-iron, golden-eagle-topped press from 1851 is the most beautiful. It was invented by American George Clymer in the early 1800s and iterations were produced into the early twentieth century. Today, some of MoP’s letterpresses are used in workshops on stone lithography, linoleum stamp-making, bookbinding, and refurbishing old presses. Other year-round MoP events feature guest speakers and demonstrations, and three annual “garage sales” offer print-related artifacts to raise money for basic operations. (With an annual budget of $300,000 and a building in need of repair, MoP’s board has begun an endowment campaign, with an eye toward eventually hiring a paid staff.)

For now, the 83-year-old Romano offers a delightful tour. He’s spent his working life in the printing industry, starting as a copyboy at the Brooklyn Eagle, and still thrives on it. He rose through the ranks at then-printing giant Mergenthaler Linotype Company, moved on to other pioneering typesetting companies, and later owned New England Printer & Publisher magazine. He also taught at the Rochester Institute of Technology for two decades and was a consultant at Apple from 1984 to 1989; he was, he claims, the only one who could successfully challenge Steve Jobs—because he knew more about typefaces. Meanwhile, in 1978, as a New England publisher, he and others had banded together to preserve the Boston Globe’s hot-metal typesetting and letterpress equipment when the company shifted to phototypesetting and offset printing. The museum opened in North Andover and in 2016 relocated to Haverhill (where some 52 tons of equipment was hauled in).

Romano moves throughout the building as if it were his home. “The oldest thing in here now, besides me,” he jokes on a tour, pointing to two display cases, is the Nuremberg Chronicle. The 1493 book, with 1,100 woodcut illustrations and Latin texts, “was like a history of the world up until that point, mostly based on the Bible.” Another coveted possession is the Sholes and Glidden typewriter manufactured by the Remington Arms Company in 1873—a black metal box with a manual paper-roller and the first QWERTY keyboard. “Q-W-E-R-T-Y-U-I-O-P,” Romano spells out. “Do you know that all the letters in the word ‘typewriter’ are in that first line? Sholes was the fifty-second person to invent the typewriter, but the only one to call it that.” Some 55 newer typewriters bank another wall, adjacent to such technological relics as an Apple Lisa desktop computer (c. 1983) and its Macintosh successor.

The last stop on the tour is the Frank J. Romano Library, which includes his own 79 books: “Every time a new printing technology came out, I wrote about it.” Sofa and chairs feature pillows bearing an “R”; there’s a collection of bookends, a Ben Franklin bobblehead, and a looping video of a Busby Berkeley film featuring dancers atop a typewriter. Here is the heart of Romano’s good humor and passion. “Someone yesterday dropped off a typewriter they didn’t want. If it’s not historic, we can fix things and sell them to support the museum. I don’t turn anything away,” he says, smiling. “Hey, if you have a museum, it’s not called hoarding.”