Art, nature, lush gardens, American monuments—the Saint-Gaudens National Historical Park, in Cornish, New Hampshire, offers a restorative retreat in times of change. Set on 190 acres, the park has long preserved the estate of Beaux-Arts sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens, whose masterworks, such as The Shaw 54th Regiment Memorial on Boston Common, across from the Massachusetts State House, made him one of the most celebrated nineteenth-century American artists. “This is a place that has always inspired people,” says Jackie Rocha, the executive director of the nonprofit Saint-Gaudens Memorial that supports the site. “The park is important because art and culture are transformative [forces].”

Open from Memorial Day through October, the site offers tours of Saint-Gaudens’s home and studio, with access to galleries holding his work along with those of contemporary artists working today. There are seasonal concerts and opera performances, too. The grounds—manicured lawns and formal gardens, with surrounding woodlands—are open for roaming and picnicking from dawn to dusk. The two-mile Blow-Me-Down Trail is perfect for family outings, and a shorter route runs along the Ravine Studio, where sculptor-in-residence Davis Fandiño works and welcomes visitors. “The park is meant to be a celebration of all American art,” says Rocha. “We sponsor all the Sunday concerts and art exhibits, which promotes awareness of the lasting legacy of Saint-Gaudens’s work, and all the ways we get to expand on that.” (See the line-up at saint-gaudens.org.)

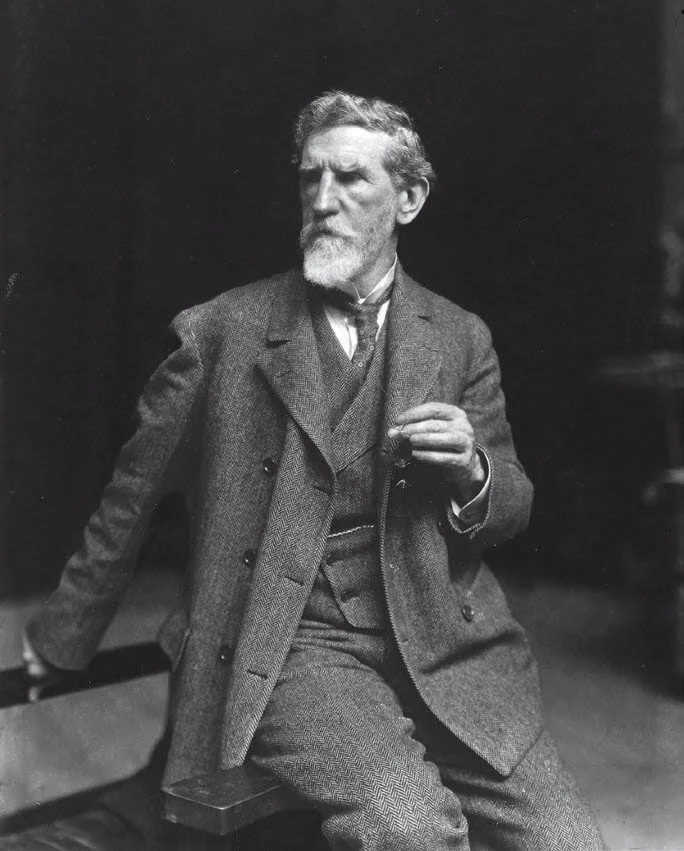

The sculptor’s life and work are marked by an enduring sensitivity and a respect for American virtues that merged realism and idealism. He was born in 1848 in Dublin, to an Irish mother and a French father, but the family quickly immigrated to New York City, where he was raised. Showing early artistic talent, at age 13 he became a cameo-cutter (some of his teenage-era cameos are on display in the newer galleries; more below) and took art classes at Cooper Union. By 1867 he was studying in Paris; then he moved to Rome, where he met his future wife, American art student Augusta Fisher Homer. Back in the United States, in 1876 he received his first major commission: a monument to Admiral David Glasgow Farragut (1801-1870). Farragut’s remarkable naval career spanned 60 years (starting as a midshipman at age nine), but he’s best known today for winning decisive battles in the American Civil War. When Saint-Gaudens’s monument was unveiled in Manhattan’s Madison Square Park in 1881, it was praised for its innovative, deep rendering of realistic detail and emotionality. He brought an imaginative liveliness to his sculptures, capturing figures in motion: Farragut stands strong, feet apart, his naval uniform blown open by the wind, looking resolutely ahead, as if on the deck of a ship.

The commissions flowed from there. In 1885, when the couple began spending summers at the Cornish property, Saint-Gaudens was already well known and began working on his Abraham Lincoln: The Man, which was revealed in Chicago’s Lincoln Park two years later. The 12-foot bronze statue depicts a contemplative Lincoln getting up from a ceremonial chair. It stands on a pedestal within an exedra designed by renowned architect Stanford White. Saint-Gaudens greatly admired Lincoln and had seen him during his inauguration and viewed his body lying in state; the statue captures a stateliness but also a powerful human sensibility, a naturalness—in Lincoln’s stance, in the way his leg is bent in step, his hand almost tenderly holding his jacket lapel.

Saint-Gaudens first rented the Cornish home as a summer residence from his friend and lawyer Charles C. Beaman, LL.B. 1865. Also based in New York City, Beaman drew the artist north as part of his plan to form what became the Cornish Art Colony. At its height, the community counted more than a hundred artists, including Maxfield Parrish and Isadora Duncan, many of whom had bought property from Beaman. In 1892, Saint-Gaudens himself purchased the property and house, which had become a hub of the colony’s social life and creativity. From 1900 to 1907, when the sculptor died of cancer, the couple lived there full time. (Augusta later formed the Saint-Gaudens Memorial, which in 1965 donated the property to the National Park Service.)

Today, visitors touring the 1817 Federal-style brick house, named Aspet for the French birthplace of Saint-Gaudens’s father, will find most of the furnishings, artwork, and personal effects just as they were when the family was present. It’s a homey place. Packed with evidence of their aesthetic taste and worldliness, there are delicate, woven Japanese rice-grass wallpaper, Asian vases and drawings, and works by friends—all mixed in with hand-me-down furniture (from Augusta’s upper-class family) and classical elements the couple added, like Greek columns on the porch.

Views from the porch sweep across the lawn and surrounding countryside, all the way to Mount Ascutney. “Individuals and friends rallied together” over time to support buying land around the site and throughout the area to save it from development, says Rocha. “We are grateful for the families that helped preserve the beautiful land because it could have been very different.”

Beside the house are formal gardens. Saint-Gaudens was involved in all the planning and development of the landscaping. Perennials bloom throughout the season—peonies in June, delphiniums in July—framed by pine and hemlock hedges, with a reflecting pool, a sculpture of Pan, and benches for resting and chatting.

A walkway through the garden and under the columned pergola leads to Saint-Gaudens’s studio: one huge open room with high ceilings and windows facing north. Visitors can roam freely, amid smaller sculptures and studies and casts of the Parthenon frieze, while learning about bronze-casting. In June, an 1892 version of Saint-Gaudens’s Diana will be returned to the space after being part of a recent traveling exhibit. His powerful, iconic statue of the nude goddess poised to release an arrow was commissioned by Stanford White as a weathervane; it topped the tower of New York’s Madison Square Garden from 1892 to 1925. (The goddess’s head was based on that of the sculptor’s longtime model and lover Davida Johnson Clark, mother of his second son, Louis.)

In all, the park highlights more than 120 works, about 75 by Saint-Gaudens that include recastings of four major sculptures. Closest to the studio is the Adams Memorial, a bronze funerary sculpture commissioned by historian Henry Adams for his wife, Clover, that marks her grave in Washington, D.C.’s Rock Creek Park. Across the estate grounds, a short walk away, the Shaw 54th Memorial anchors what was once a bowling green, while the Farragut and Lincoln monuments are part of a complex of newer outbuildings connected by a Roman-style atrium with reflecting pool—another lovely spot to take a break.

The buildings’ galleries feature some of Saint-Gaudens’s earliest works: miniature relief sculptures known as cameos. He apprenticed as a cameo-cutter for six years, learning this intricate, delicate art and later making use of it to craft details in his massive monuments. These talents also surfaced when, in 1905, President Theodore Roosevelt asked him to redesign a $20 gold “double-eagle” coin. It was among the last pieces he created. On the obverse, he paid homage to classical Greek and Roman culture, creating a heroic figure of Liberty backed by bold sun rays. Like Lincoln, Farragut, and Diana, she’s in motion, striding forward. Her hair and gown are whipped by the wind, yet her torch is held aloft, unwavering. It’s a bold, clear vision of America, reflecting a belief in what the nation stood for, rendered in an abiding blend of realism and idealism.