The Phi Beta Kappa Literary Exercises, held the Tuesday morning of each Commencement week in Sanders Theatre, are in a way the most intellectual and cultural of the graduation events, complete with poems, song, and a history-laden oration (see program).

Chapter president Howard Georgi, Mallinckrodt professor of physics and master of Leverett House, opened the 219th exercises with a bit of history, enlivened with the observation that the Yale chapter was revived in 1884, just 125 years ago. He also sounded a theme that will no doubt recur this Commencement week, referring to times that are "turbulent and difficult" and thanking President Drew Faust and Harvard College dean Evelynn Hammonds for attending even as they work diligently to sustain the University's future.

Chapter vice president Ann Blair, Lea professor of history, recognized the three winners of PBK teaching prizes, which are voted by the honored students themselves: assistant professor of statistics Joseph Blitzstein; Marquand professor of English Daniel Donoghue; and Francke professor of German art and culture Jeffrey Hamburger (who is in Germany with students; his award was accepted by his retiring colleague Irene Winter, Boardman professor of fine arts).

Emeritus professor Everett Mendelsohn conferred honorary chapter membership on Frank Griswold III '59, former principal bishop of the Episcopal Church; Jane Jervis '59, historian of science and former president of Evergreen State College; Roberta S. Karmel '59, lawyer, law professor, and the first woman to serve as commissioner of the Securities and Exchange Commission; the retiring Ralph Mitchell, McKay professor of applied biology; and poet Albert Goldbarth.

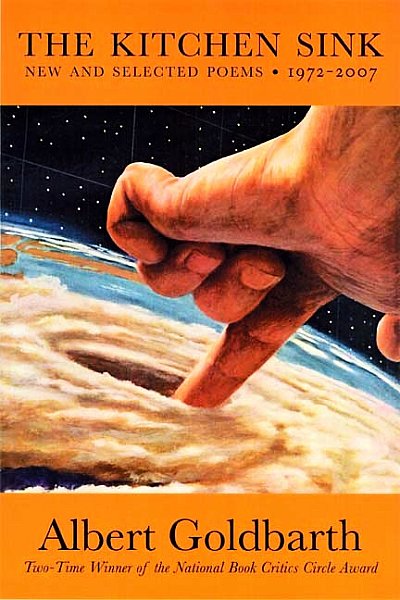

Blair introduced Goldbarth, the only poet to win the National Book Critics Circle award twice, and winner of the Mark Twain Award for humorous poetry. She alluded to wide reading-including of comic books and instruction manuals for toys-and his remarkable collection of tin toys and manual typewriters (see https://www.poetryfoundation.org/journal/article.html?id=179326).

Goldbarth said he would read two poems. The first, "Voyage" (audio appears above, text here), appears in The Kitchen Sink: New and Selected Poems, 1972-2007. Facing an audience of "smart people," he said, he wished to present a "smart-person protagonist," such as Darwin, who is featured in this poem, about optimism and moving forward into the future with vim and vigor. He saw that attitude as an antidote to the worldview of Michelle Pfeiffer, who said in a recent magazine interview he had read that there were perils in being "too smart"-that "that kind of personality can sometimes lead to hopelessness." To that he would then append a brief new poem, "Days With the Family Realist" (audio appears above, text here), which he intended to temper the first poem's perhaps overweening optimism. In it, he recalled his grandmother's earthy, deflating advice, in the face of a man "planning his own small/parthenons and relativity theories,/bank heists, moon shots, deathless poems." Her advice: "Go milk a fish."

The Kitchen Sink: New and Selected Poems, 1972-2007 (Graywolf Press)

As it happened, Goldbarth's Darwinian theme fit with the subject of the subsequent oration. This year's orator, Gurney professor of English literature and professor of comparative literature James Engell, chair of the department of English (see his recent Harvard Magazine review here; see his faculty profile here), made the most of his opportunity by delivering a powerful, 47-minute address on the urgency of changing human habits, education, and ethics to effect radically needed changes in mankind's impact on the natural environment.

The oration is titled "Planting Beach Grass: Managing the House to Sustain It," a reference to that hero of environmentalists and writers, Henry David Thoreau. "In his journal about Cape Cod," Engell noted, Thoreau observed that residents of Truro, a storm-washed Outer Cape beach community, "were regularly warned...to plant beach grass.... In this way...they built up again that part of the Cape...where the sea broke over in the last century.... Thus Cape Cod is anchored to the heavens, as it were, by a myriad little cables of beach-grass, and, if they should fail, would become a total wreck, and ere long go to the bottom"-as lovely a passage on his broader theme as one might find.

Engell also brought in contemporary concerns about the economy by making analogies to overdrawing mankind's balance with nature: "Nature has zero ethical responsibility for us," he said. "She will let us take out large, unsecured loans. When we can no longer meet payments, she will silently and surely, with no sentiment whatsoever, repossess the house. After all, we're only tenants.”

Fueled by good intentions and entrepreneurship, but also by greed and self-interest wrongly understood, the recent financial meltdown took a decade to develop. Fueled by the same human qualities, the environmental meltdown has taken two centuries to heat up. It's insidious, pervasive, and fiendishly difficult to calculate, its reversal inestimably harder to achieve. The environmental meltdown is far more dangerous.

As might be expected of a literary scholar, and coeditor of the recently published Environment: An Interdisciplinary Anthology, Engell made frequent and rich use of texts, from Romeo and Juliet to William James, throughout his address. In perhaps the central passage of his argument, Engell addressed the complacency-call it "habit"-that prevents people from seeing the emergencies before them and from acting appropriately:

The environmental challenges we've created require: basic and applied science, technological innovation, entrepreneurial business, institutional actions, organizations and movements dedicated to change, as well as government regulation and incentives.

Three elusive but indispensable elements are also needed: reformed habits, redesigned learning, and new ethics. Inaction on any of these three fronts will thwart all those other efforts. Aristotle remarks that courage is the most important of virtues because without it the others cannot be exercised. Without changed habits, learning, and ethics, we will not only not be able to manage our house in the environmental era, we will not even be able to conceive of actions for adequate management. The great change must first come from within.

Habit is a huge force. Plutarch and Montaigne call it second nature. It's more than that. Habit is twice nature. William James in the brilliant chapter on habit in his Principles of Psychology (1892) states, "Habit is...the enormous fly-wheel of society" (PP, ch. 10). More than anything else, it resists change. The worst habits are insidious in the scientific and ethical sense: slow, hurting over time by imperceptible degrees, therefore easily ignored or denied, addictive, stealthy, treacherous, literally lying in wait for ambush. Smoking is insidious. Extinction of a species is often insidious. Burning big amounts of coal is insidious. Business as usual is insidious.

Habits are values in disguise. They constitute what we buy to wear and what we build to live in, habit and habitat. Our habits can easily destroy the habitats of other creatures. The killer is that because insidious habit is so slow, and so thorough, none of it rises to a "catastrophe." Yet, like lung cancer, it's usually too deadly to reverse. The enormity of such habit is that any warning that it's creating a crisis in slow motion seems powerless to stop the addiction; which is the essence of tragedy. Shakespeare's King Lear doesn't listen to his Fool. When the king at last recognizes his own foolishness for what it was all along, it's too late to stop the suffering.

Moreover, whenever a short-term crisis comes along-the ailing economy, flu, violence at home or abroad, immigration woes, or problems with Medicare, we tend to forget on what they all depend. Every day, slowly but certainly, the way we treat the natural world affects health, the risk of war and terrorism, motives for immigration, all future economies, and resources for social programs and sustainable jobs. The affluent have abused the natural world and now fall short in their responsibilities to help the developing world avoid more abuse. Giving comparatively little in foreign aid and structuring loan and trade agreements as we have, we fail to provide poorer nations and the people in them with the help they need to obtain a higher standard of living, to stop deforestation, pollution, and other damaging practices.

In the last presidential campaign, Americans rated environmental concerns at number 17, like fake window shutters instead of foundation stones for the house itself. It's good leadership to have an administration that puts them high, in concert with other concerns. The current administration knows that in the end a better economy depends dramatically on a better environmental economy.

Yet, habits die hard, especially in Congress. Although it could cover the budget shortfall of a national healthcare plan, we're unlikely this year to have cap and trade legislation for carbon, and more unlikely to pass what we really need, a carbon tax.

All this means sacrifice, an emphatic change of personal habit and custom, those elusive qualities long regarded at the core of a liberal education. And it means smarter use of natural capital, starting with the trillions of megawatts of power falling on Earth each day from the Sun, and, through the Sun and Earth's rotation, latent in wind.

Let's see this another way. If it were known that an asteroid hurtling toward Earth would, with a probability increasing each month, strike this planet in 40 years, raise sea levels 25 feet, put one-quarter of known species in danger and force many extinctions, set off plagues and disease, flood parts of nations, submerge populated islands, render coasts uninhabitable, bring longer droughts and larger floods, permanently evacuate thriving cities, intensify hurricanes, super-typhoons, and tornadoes, and shorten or end the lives of millions, then every government would be working furiously to discover how that asteroid could be diverted or destroyed. There is no such asteroid (as far as we know), but all the rest in this scenario is likely true, with evidence for it mounting a little each hour. It's happening insidiously, from billions of daily habits thrown together like unscrupulous pebbles until their combined force matches the impact of a heavenly body. It's our own burning of carbon.

To those graduating, you now start to exert power that will grow, domesticated through technologies you will invent, guided by policies you will formulate, enforced by laws you will write, enlivened by goods you will produce, exercised by societies you will help to govern. Yet, the bedrock of all the power you exert comes straight from habits of thinking and acting that even now are tempering themselves into values, values that hold Earth and all its inhabitants in the balance.

Engell wed these overarching observations with specific instances of change he felt were urgently needed, none more daunting and imperative than addressing climate change. "Between now and 2050," he said, "in this country, we need to change from emitting 20 tons of carbon dioxide per person per year to one."

Addressing his audience directly, and incorporating his own youthful experiences, Engell said:

If the odds stick, it's a fair bet one or more of you will receive a Nobel Prize, a good chance at a Pulitzer, and an excellent outlook to win a MacArthur "genius grant." Then, remember what William James said-and had they existed in his day, he could have won all three of those honors: "Genius, in truth, means little more than the faculty of perceiving in an unhabitual way" (PP ch.20). We're now engaged in a revolution whose aim is not to secure freedom from a tyrant, but to free us from the tyranny of our own habits.... When I was a student, I sat in this theater reading Robert Frost's poem "It's Almost the Year 2000" and thought, foolishly, how far away that year was.

When I was a boy, at night, in high summer, I'd hear through screens of the dormered bedroom in the lakeside cottage my grandfather and uncle built, the voice of the whippoorwill, repeated from the forest floor, moving across the old dirt road. It haunted my nights and promised an enchanted world in this world, not to dominate or develop, but to receive as a natural blessing that makes life richer, more bearable, more lovely. The whippoorwill is gone, deeper into the woods. Ornithologists don't know exactly why the bird has declined so drastically, but I suspect my own habits have had something to do with forcing it on its way.

In his conclusion, Engell underscored the inevitability of action for those who wish to live a moral life:

The final dismissive response to an environmental era is, "I know all this. Tell me something I don't know." A clear reply comes from William James: "No matter how full a reservoir of maxims one may possess, and no matter how good one's sentiments may be, if one have not taken advantage of every concrete opportunity to act, one's character may remain entirely unaffected for the better" (PP, 1892, ch.10).

Not to exaggerate, but for plain emphasis, let me say that none of us can yet conceive how unrecognizable, even unimaginable, will need to be changes in our habitual actions. We will be as amazed as those first passengers riding in a railway carriage who feared that traveling at the ungodly speed of 25 miles an hour would annihilate their bodies and rip apart their limbs to send them flying through space.

Finally, he held out the promise of success for those who embrace change:

There are solutions, even with off-the-shelf technologies available now. It is possible to manage this house. If reform is everywhere within, then the leadership you now begin to assume, while arduous, will achieve success, success shared with other communities and passed on to the next generation with decent hope, not massive debt. Let us continue our sacrifices so that we may sustain our gifts. There is in life a sustainability of spirit that, if we greet it generously, intelligently, compassionately, links generation to generation, and also humanity to its larger house, which is our only home.

In closing the exercises, Howard Georgi made reference to Harvard's brave new frontier: the coming academic calendar change that will bring Commencement forward in time next year. He adjourned the Phi Beta Kappa exercises until May 25, 2010.