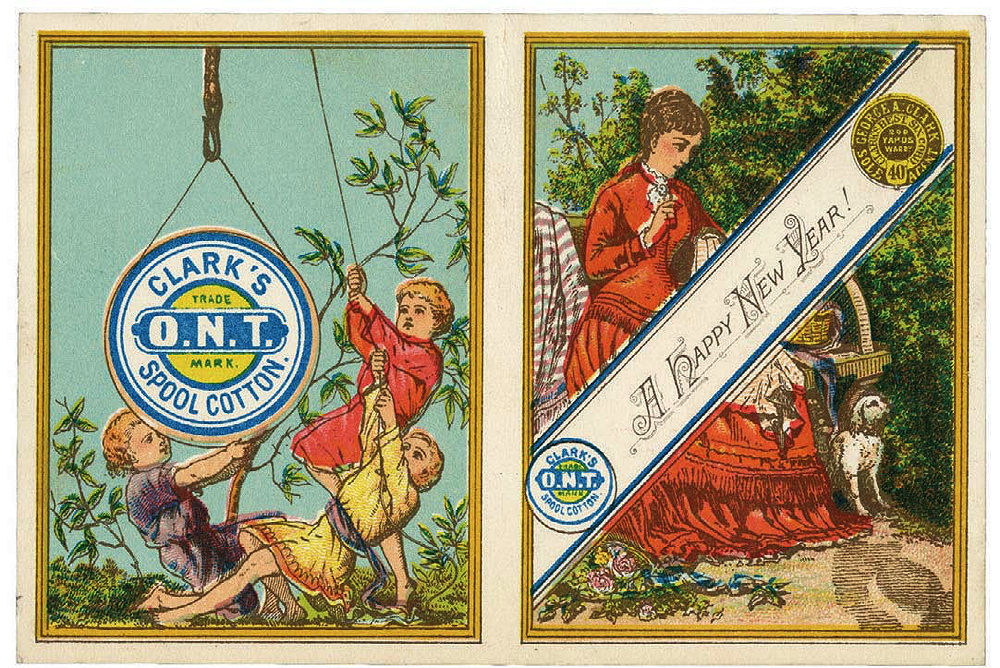

In the United States, the late nineteenth century was an age of invention. Machines for sewing and laundering clothes heralded relief from domestic drudgery. Packaged foods, including tinned meats and breads, made their mass-market debut, and patent medicines—reassuringly labeled “vegetable only”—claimed to cure virtually any digestive ailment, from “dyspepsia” to “biliousness.” Meanwhile, a growing rail system provided a way to distribute this explosion of consumer products. Manufacturers needed to showcase their goods. So, at checkout in the local general store of 1880, the proprietor might have slipped into your package a colorful trade card—to be discovered later, perhaps by the children of the household, to their delight.

Trade card courtesy of the Baker Library Historical Collections/Harvard Business School

Trade cards were designed to appeal even more so to women, who made most of the household purchasing decisions. The cards often featured images of flowers, animals, and cherubic boys and girls, or patriotic icons like Uncle Sam and Lady Liberty, to promote products or services: skin creams and corsets, teas, tobacco, and tailors.

Trade cards courtesy of the Baker Library Historical Collections/Harvard Business School

They provide “a fascinating glimpse at printing, advertising, and marketing technology of the time,” says Christine Riggle, the special collections librarian for printed materials at Baker Business Library, which has digitized about a thousand examples from its collection of advertising ephemera. Often collected in albums made specifically for the purpose, most were rectangular, and ranged between the size of a playing card and postcard. The earliest examples, dating to 1860, were printed with black ink only. But after the Civil War, chromolithography allowed inexpensive, industrial-scale color printing for the first time. Other innovations followed. Die-cut cards enabled manufacturers to mimic the shape of their products. The card advertising David’s Prize Soap (below) takes die-cutting a step further: a fold allowed prospective customers to “open the lid” of the soap box and see just how pleasant a concert in the drawing room could be. The playful peek-a-boo boy on a donkey advertising Standard Java coffee (recto and verso, above), is another type of metamorphic, or “before and after,” card. Particularly inventive forms took advantage of optical illusions. Putting her nose against one example, a lady could see a model try on a black corset. Turning another card upside down would reveal a new image.

Printed catalogs and magazine advertising began displacing trade cards in the 1890s. But their legacy remains. The holiday greeting-card industry began with messages from advertisers wishing their customers “Merry Christmas” or heralding a new year.