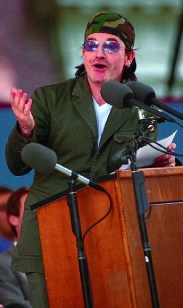

Graduating seniors chose U2 lead singer Bono to give their Class Day address. Born Paul Hewson, he allegedly picked up his nickname from Bono Vox, bad Latin for "good voice." He spoke of how he reached a new personal level of "unhip." Excerpts follow.

|

Bono |

Photograph by Jim Harrison |

My name is Bono, and I am a rock star. Now, I tell you this not as a boast but more as a kind of confession. Because in my view the only thing worse than a rock star is a rock star with a conscience--a celebrity with a cause --a placard-waving, knee-jerking, fellow-traveling activist with a Lexus and a swimming pool shaped like his head.

I'm a singer. When you need 20,000 people screaming your name in order to feel good about your day, you know you're a singer.

I owe more than my spoiled lifestyle to rock music. I owe my worldview. Music was like an alarm clock for me as a teenager and still keeps me from falling asleep in the comfort of my freedom.

Rock music to me is rebel music. But rebelling against what? In the Fifties it was sexual mores and double standards. In the Sixties it was the Vietnam War and racial and social inequality. What are we rebelling against now?

If I am honest, I'm rebelling against my own indifference. I am rebelling against the idea that the world is the way the world is and there's not a damned thing I can do about it. So I'm trying to do a damned thing.

But fighting my indifference is my own problem. What's your problem?

Let me tell you a few things you haven't heard about me, even on the Internet. I became a student at Harvard recently, and I came to work with Professor Jeffrey Sachs at the Center for International Development to study the lack of development in third-world economies due to the crushing weight of old debts.

It turns out that the normal rules of bankruptcy don't apply to sovereign states. Listen, it would be harder for you to get a student loan than it was for President Mobutu to stream billions of dollars into his Swiss bank account while his Congolese people starved on the side of the road. Two generations later, the Congolese are still paying.

So here I was, representing a group that believed that all such debts should be cancelled in the year 2000. We called it Jubilee 2000. A fresh start for a new millennium.

It was based out of London--with huge support from Africa. It was taking off. But we were way behind in the U.S.

We had the melody line, so to speak. But in order to get it on the radio over here, we needed a lot of help. My friend Bobby Shriver suggested I knock on the good professor's door. And a funny thing happened. Jeffrey Sachs not only let me into his office, he let me into his Rolodex, his head, and his life for the last few years. So in a sense he let me into your life here at Harvard. A student again--I was three weeks in a college before that, all right?

Then Sachs and I, with Bobby Shriver, hit the road like some kind of surreal crossover act. A rock star, a Kennedy, and a Noted Economist crisscrossing the globe like the Partridge Family on psychotropic drugs, with the Pope acting as our--well--agent. It was a new level of "unhip" for me, but it was very cool.

While I'm handing out trade secrets, I also want to tell you that Larry Summers, your incoming president, the man whose signature is on the American dollar, well he, too, is a nutcase--and a freak.

Look, U2 made it big out of Boston, not New York or L.A., so I thought if anyone would know about our existence it would be a treasury secretary from Harvard. No. When I said I was from U2, he had a flashback to Cuba 1962.

How can I put this? And don't hold it against him--Mr. Summers is, as former President Clinton confirmed to me last week in Dublin, "culturally challenged."

But when I asked him to look up from "the numbers" to see what we were talking about, he did more than that. He did the hardest thing of all for an economist --he saw through the numbers.

And if it was hard for me to enlist Larry Summers in our efforts, imagine how hard it was for Larry Summers to get the rest of Washington to cough up the cash. To really make a difference for the third of the world that lives on less than a dollar a day.

He was passionate. He turned up in the offices of his adversaries. He turned up in restaurants with me--a rock star--to meet the concerns of his Republican counterparts. (If you're called up before the new president of Harvard and he gives you the hairy eyeball, drums his fingers, and generally acts disinterested, it could be the beginning of a great adventure.)

|

A Bono's-eye view of Tercentenary Theatre |

Justin Ide/Harvard News Office |

I'm telling you these stories because all the fun I had with Jeff Sachs and Larry Summers was in the service of something deadly serious. When people around the world heard about the burden of debt that crushes the poorest countries, when they heard that for every dollar of government aid we sent to developing nations, nine dollars come back to us in debt service payments, people got angry.

In fact, they more than got angry. They took to the streets in what was without doubt the largest grass-roots movement since the campaign to end apartheid. Politics is, as you know, normally the art of the possible, but this was something more interesting. This was becoming the art of the impossible. We had priests going into pulpits, we had pop stars going into parliaments. The Pope put on my sunglasses for a photo session. We had the religious right acting like student protesters. And finally, after a floor fight in the House of Representatives, we got the money--four three five million. And more importantly this leveraged billions of dollars from other rich countries.

So far, 23 of the poorest countries have managed to meet the sometimes over-stringent conditions to get their debt payments reduced--and to spend the money on the people who need it most.

I could tell you a little story about one remarkable man in rural Uganda, Dr. Kabira. In 1999, measles killed hundreds of kids in Dr. Kabira's district. Now, thanks to debt relief, he's got an additional $6,000 from the state, enough for him to employ two new nurses and buy two new bicycles so they can get around the district and immunize children. Last year, measles was a killer. This year, Dr. Kabira saw less than 10 cases.

I just wanted you to know what we pulled off with the help of Harvard. But I'm not here to brag. And not just to say "thanks." I think I've come here for another reason--to ask you for your help. This is a big problem, and we need some smart people working on it.

When the history books make records of this moment, we will be remembered for two things: the Internet, probably, and the everyday holocaust that is Africa--25 million HIV positives who will leave behind 40 million AIDS orphans by 2010 in sub-Saharan Africa alone.

It's an unsustainable problem for Africa and, unless we hermetically seal the continent and close our consciences, it's an unsustainable problem for the world. But it's hard to make this a popular cause because it's hard to make it pop, you know?

Didn't John and Robert Kennedy come to Harvard? Isn't equality a son of a bitch to follow through on? Isn't "love thy neighbor" in the global village so inconvenient? God writes us these lines but we have to sing them, take them to the top of the charts. But it's not what the radio is playing, is it?

We've got to follow through on our ideals or we betray something at the heart of who we are. Outside these gates, and even within them, the culture of idealism is under siege, beset by materialism and narcissism and all the other "isms" of indifference. And their defense mechanisms --knowingness, the smirk, the joke.

Civil rights in America and Europe are bound to human rights in the rest of the world. But these thoughts are expensive, they're going to cost us. Are we ready to pay the price? Is America still a great idea as well as a great country?

When I was a kid in Dublin, I watched in awe as America put a man on the moon. We thought, wow, nothing is impossible in America! Nothing is impossible, only human nature, and it followed because it was led.

Is that still true? Tell me it's true. It is true, isn't it? And if it isn't, you of all people can make it true again.

Courage and Folly

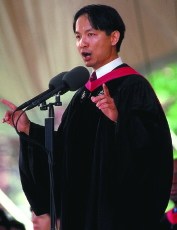

Leng Leroy Lim, M.Div. '95, M.B.A. '01, is a native of Singapore, an Episcopal priest, and now an employee of the management consulting firm Marakon Associates in San Francisco. He intends to continue his ministry as a prison counselor. He delivered the graduate English address, part of the formal Commencement exercises. Excerpts follow.

|

Lim |

Photograph by Jim Harrison |

Six years ago, I graduated from Harvard Divinity School. I returned, this time to the Business School for my M.B.A. Some people have asked me whether I am trying to serve two masters, God and money. I say to them that I am serving three masters: Visa, Mastercard, and American Express.

I have learnt much here because this very place itself teaches me. In front of you stands Memorial Church, which recalls Harvard students who died in battle, and stands as a testament to courage. Behind you sits Widener Library, given by Eleanor Widener in memory of her son, Harry, who drowned at sea. The building speaks of the gift one generation makes to the next.

But Widener Library also symbolizes something else. It reminds us that Harry Widener perished because he was on the Titanic. The ship was the glory of industrial technology, built for luxury, built to be unsinkable, built with spaces on the life-boats for half of those on board. The building therefore stands as a witness to the tragedy that occurs when our achievements are paired with our hubris.

Likewise, Memorial Church is also a monument to misjudgment. It commemorates World War I, a war which claimed 10 million lives, a war blundered into by an educated elite. Eleven thousand Harvard students joined the war, almost twice as many as are graduating today. Three hundred and seventy of them died in it. But the cost went beyond the dead. The vengeance of the victors, and the humiliation of the defeated, created a field of hatred, upon which Hitler would later plant his evil.

These buildings speak with eloquence of the courage and ingenuity of human beings. But they also force us to reckon with the folly, hubris, and delusions of which intelligent people are capable.

At Harvard, I have discovered, as you must have, the joy of mastering knowledge. Yet it is in those moments of supreme confidence that we build our Titanics. We are tempted by our convictions to close off inquiry, to become fundamentalist or deterministic, and so believe we cannot be wrong. But if we have learnt well the life of the mind, so exemplified by this library, then there is an undying curiosity of the other person's experience, and a healthy skepticism of our own position.

The challenge for our untested generation may not be to some heroic sacrifice. Instead, ours is to ensure that monuments to such tragic sacrifices need never be built.

Let not the generation a century from now say we squandered this moment. Rather let them say that we accepted the challenge of global leadership. We stopped global warming. We built a prosperous global community with meaningful wages and opportunities.

And let them also say that we did the small things well: we served the next generation by having changed their diapers; we preserved the dignity of those different from us; spoke the truth in the face of the status quo; and curbed our hubris.

Widener Library and Memorial Church call us this day to shoulder the mantle of leadership and service. They call us to trust and commit, and so come to know faith; to dream and dare, and so come to know hope; and to do with others what we cannot do alone, and so come to know love; and by this, honor the past and transform the future.

"We Wager"-- An Envoi

Neil L. Rudenstine began his exuberant final Commencement speech by exploring a familiar theme: the motive force at the heart of a great university's "restlessness, energy, and even endurance." Drawing from Dr. Johnson, Josiah Royce, Henry James, and Albert Einstein, he plumbed the obsessive nature of the quest for consequential new knowledge. Invoking another favorite author, he then addressed the university's educational mission--and, perhaps, offered a history lesson.

If curiosity and the search for order propel the university forward, then it is education--the preparation of individuals for lives of effective action--that completes the circle of what Harvard and other universities attempt to do. In this respect, the development and the calibration of finely tuned judgment, leading finally to action, is clearly one of the critical tasks of what we call "education."

|

Rudenstine |

Photograph by Jim Harrison |

Lady Asquith once said of Sir Stafford Cripps--who served in several governmental positions--that "he has a brilliant mind, until he makes it up." And Winston Churchill, who had a tendency in Parliamentary debate to elaborate ideas rather far beyond strict necessity, was once interrupted by a colleague who remarked that he wished to remind the Right Honourable Gentleman that a monologue was not the same thing as a decision.

Learning to make up one's mind, to judge as accurately as possible, and then--despite all the variables and uncertainties--to act decisively on the basis of judgment: all of these complex and interconnected processes are absolutely integral to an education in the liberal arts and sciences. They can (up to a point) be taught; and (up to a similar point) be learned, in dozens of different ways, especially in a residential college or university.

In fact, those moments in experience when we can actually witness the mind in motion, trying to reach toward judgment, are to me--personally--always arresting. A vivid and also poignant example occurs in the very great book, The Education of Henry Adams, when the young Adams--who had graduated from Harvard in 1858--had his first and only meeting with Abraham Lincoln, who had just been elected President in 1860. Writing about this encounter, nearly half a century after it took place, Adams described his own attempt to make an assessment of Lincoln--and Lincoln's apparent effort to assess his own situation. Here is the passage:

Had young Adams been told that his life was to hang on the correctness of his [judgment]...of the new [President's abilities]..., he would have lost. He saw Mr. Lincoln but once, at the melancholy function called the Inaugural Ball. Of course [Adams] looked anxiously for [signs] of Mr. Lincoln's character. He saw a long, awkward figure; a plain ploughed face; a mind, absent in part, and in part evidently worried by [the] white kid gloves [he was wearing]; features that expressed neither self-satisfaction nor any other familiar Americanism, but rather the same painful sense of becoming educated, and of needing education, that tormented Adams himself...; above all, [Mr. Lincoln con- veyed] a lack of apparent force....No man living needed so much education as the new President, but...all the education he could get would not be enough.

Apart from the drama here--the real immediacy of significant history taking place before our eyes--the passage captures brilliantly the chance meeting of two consequential figures, each in need of--and in search of--education in its most important dimensions. Adams, trying to evaluate Lincoln, decides--wrongly--that the President lacks the necessary force to meet the challenge before him. And Lincoln, ill at ease, alone, apparently inadequate and un-self-confident, seems to be groping painfully for the knowledge, the information, the intuitive grasp of how the fields of force around him are aligned, and finally for the ability to weigh and accurately judge all the considerations that are necessary, in order to act wisely.

This development and exercise of judgment, and the equally important task of helping students and ourselves to understand something about the range and likely dynamics of potential actions: these difficult, often baffling, always incomplete efforts are nonetheless fundamental to what Harvard and other universities attempt to do. Whether we manage to achieve our goals in this arena, is one of the genuine mysteries of our vocation. It requires a calculus of values well beyond our capacity to make. Here, as in so many spheres of life, we are compelled to wager.

In the end, we wager that those students (and others) who are likely to have more knowledge; who have more ability to analyze carefully as well as to imagine creatively and rigorously; who have been strongly tested and held to high standards; and who have engaged seriously with the activity and energies of a great university: we wager that such individuals are likely to lead, not only lives of personal fulfillment, but also effective lives in the service of others and of society as a whole.

It is a very reasonable wager--in fact, I do not know a better one. But it is, like most significant aspects of life, based on a good deal of faith and hope, as well as on the cumulative store of experience, knowledge, and judgment that we possess.

All of us present this afternoon have wagered a great deal together in these past 10 years at Harvard. For my own part, I would not hesitate a moment to make the very same wager again--except for the convenient fact that there can be no repeat performances in life.

So let us with good cheer declare that these revels are now about to end. Our actors are about to dissolve and vanish into air, leaving behind the cloud-capped towers and discreet temples of learning in this familiar and beautiful Yard.

Angelica and I thank you for the privilege of having been able to serve this matchless university in your company. We have been moved by your friendship, your help, and your support. We look forward to future reunions in the sunlight and shade of this beneficent and peerless place, which we are all fortunate to be able to think and to call our own.

Au revoir!

Operae Merces Digna

|

Crawford |

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard News Office |

"Illos etiam plaudamus qui laboraverunt, atque insederunt, ut operae mercedem dignam acciperent, et speremus negotii discipulos de iustitia didicisse!" said Corrinne S. Crawford '01, of Eliot House and Burlington, Vermont, in her "Latin Salutatory" Commencement morning. She wore a sticker that read "Harvard Living Wage Now" (see page 64), and this is what she meant: "Let us also applaud those who worked, and sat in, for a living wage. They, I hope, have taught the Business School students something about justice!"