If a nation's crime rate is any measure of its gentility, the United States is getting downright civilized. From 1990 to 1999, crime--which for the FBI's statistical purposes includes offenses such as murder, rape, robbery, and arson--dropped 19.6 percent, reaching the lowest level ever recorded, according to Bureau of Justice statistics. This reassuring trend can be explained in several ways, from an improved job market to community policing efforts to new gun-control initiatives. But the factor that seems to get the most credit for our safer streets is the increased rate of incarceration. Some studies attribute as much as 25 percent of the drop in crime to this phenomenon alone.

Incarceration at federal and state institutions now costs the nation $40 billion per year. Whether one regards this prison-population boom as a source of satisfaction or as a symbol of just how uncivilized our society has become, few would dispute that putting convicts behind bars is a rather straightforward way to halt (or at least limit) their ability to pursue unlawful activity.

|

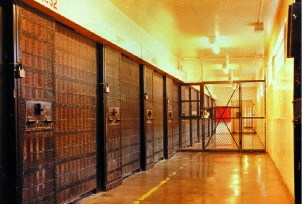

Cells on "death row" at California's San Quentin Prison, photographed in 1996. |

| Associated Press |

But Anne M. Piehl, associate professor of public policy at the Kennedy School, asks a troubling question: What if increasing the number of prisons doesn't directly affect the rate of crime? In a paper titled "The Crime-Control Effects of Incarceration," coauthored with Raymond V. Liedka and Bert Useem of the University of New Mexico at Albuquerque, Piehl takes a closer look at how the ultimate "time out" affects the prevalence of crime.

"We were interested in considering the possibility of a nonlinear relationship between prison and crime," Piehl explains, "despite the fact that the prison population has quadrupled [to two million inmates] over the last 20 years." (Though the crime rate has dropped, it has not fallen to 25 percent of 1980 levels.) Piehl and her coauthors examined the variation in state prison populations over the last 25 years relative to the crime rate and concluded that a 5 percent drop in the crime rate is a more accurate estimate of the effects of increased incarceration rates. "If you think the criminal justice system is doing its job in getting some of the more serious offenders off the street, then an expansion in prison size beyond these current, already high levels wouldn't have as much of an effect as it would have had 10 years ago," she observes. "When the prisoner population is already up around two million, building more prisons will have less of an effect on the crime rate than it would have when that population was around 100,000, for example."

The researchers also separated the prison population into drug offenders and non-drug offenders. "One of the ways in which the debate about the association between prison and crime is not very nuanced is that the use of prison space is put into one lump," Piehl notes. Although violent offenders have been responsible for more than half the increase in the state prison population since 1990, the "war on drugs" has also helped fill houses of correction. The number of drug offenders in state prisons grew from 19,000 in 1980 to 236,000 in 1998, an increase of more than 1,200 percent.

Piehl observes that, due to the pervasiveness of drug crime, the number of prisoners incarcerated for such offenses may more accurately reflect the number of police officers devoted to drug enforcement than the effectiveness of prison as a deterrent. "It's like measuring traffic violations," she suggests. "You could say that Cambridge is experiencing a drop in parking tickets, when the real cause is that a police officer was on vacation."

Another overlooked factor is the rate at which an inmate's criminal "offending rate" decays over time. In other words, middle-aged inmates scheduled for release might not be as likely to raise hell as they were when they went into the big house 20 years ago. That decreased potential for unlawfulness is not taken into account when considering the relation of the prison population to the crime rate, simply because it is impossible to pin down what motivates criminal behavior at any stage in a person's life. Despite this difficulty, Piehl suggests that it's important for policymakers to consider factors that the statistics don't reveal, and to avoid blanket theories when it comes to such a powerful and disruptive tool as imprisonment.

"Incarceration is a very intrusive action by the government, with high financial costs and large consequences for individuals, their families, and the communities in which they live," she notes. "Sometimes it's the best response to certain kinds of offenders and offenses, but it's a sanction we need to use judiciously."

~Julia Hanna

Anne Piehl website:

https://ksghome.harvard.edu/~.apiehl.wiener.ksg/