|

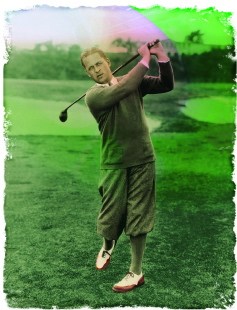

| Jones connects at the Flintridge Golf Club in Los Angeles in 1931. |

| Photograph courtesy Sidney L. Matthew. Photomontage by Bartek Malysa |

Robert Tyre Jones Jr. '24, the amateur golfer who never took a lesson and stored his clubs most winters, nonetheless is described by the Oxford Companion to World Sports and Games as "probably the greatest player the game has known." From 1922 to 1930, he placed first or second in 11 of 13 U.S. and British Open championships, winning seven times and losing twice in playoffs. He was a five-time U.S. Amateur champion who captured his first British Amateur in 1930, the year he won the three other major golf titles of that era--the U.S. Open and Amateur, plus the British Open--to complete golf's only recorded "Grand Slam" of all four major championships in one year. Then he retired from competitive golf; at age 28 he had already become the only individual ever to receive two New York City tickertape parades.

Jones's modesty, humor, and generous spirit further enhanced his stature. "As a young man, he was able to stand up to just about the best that life can offer, which is not easy, and later he stood up with equal grace to just about the worst," wrote the New Yorker's Herbert Warren Wind. At the 1925 U.S. Open in Worcester, Massachusetts, Jones's ball moved in the long grass on the steep bank by the eleventh green as he addressed it; he insisted, over official objections, on adding a penalty stroke to his score. When praised for his honesty, he retorted, "You might as well praise me for not breaking into banks. There is only one way to play this game."

Jones was a sickly child who could not eat solid food until he was five, the year his family spent the summer near the East Lake golf course outside Atlanta, their hometown. "I wish I could say here that a strange thrill shot through my skinny little bosom when I swung at a golf ball for the first time," wrote Jones in his 1927 autobiography, Down the Fairway, "but it wouldn't be truthful." Even so, by age six he was teaching himself golf by following East Lake's best player around and imitating his swing, and at 14, the blue-eyed, tow-headed prodigy became the youngest player ever to enter the U.S. amateur championship.

The precocious youth was a hotheaded perfectionist who once, after missing an easy shot, took a full pitcher's windup and threw his ball into the woods, and another time chucked his putter (nicknamed "Calamity Jane") over the heads of the gallery and into the trees. The influence of O.B. "Pop" Keeler, an Atlanta sportswriter some call the first sports psychologist, helped settle him down. The older man became a mentor, friend, confidant, and publicist for Jones, traveling 150,000 miles with him and witnessing all 13 of his major championships.

After graduating from Georgia Tech in mechanical engineering in 1922, Jones added an A.B. in English from Harvard in 1924. To prepare for the College, he read Cicero. At the time, he was nearing the end of his "seven lean years," during which, despite his obvious immense talent, he had been unable to win a major title. "I remember also envying Cicero because he evidently thought so well of himself," Jones recalled. "If only I thought as much of my golfing ability (I considered) as Cicero thought of his statesmanship, I might do better in these blamed tournaments." Having exhausted his golfing eligibility at Georgia Tech, Jones earned his "H" as assistant manager for Harvard's golf team, whose top six players once lost to him in an informal match. (Though he never competed for the Crimson, Jones is in the Varsity Club's Hall of Fame.)

In 1924, Jones married Mary Malone; they had three children. He studied law for a year at Emory and was admitted to the Georgia bar in 1928, worked in his father's law firm, and pursued business interests with Coca-Cola and Spaulding sporting goods. In the 1930s Warner Brothers produced 18 instructional golf films of Jones giving tips to Hollywood stars, a deal that brought him $250,000. (The title of the first film series, How I Play Golf, presaged that of Tiger Woods's current bestseller. Asked on television to name his "dream foursome," Woods proposed Ben Hogan, Jack Nicklaus, himself--and Bobby Jones.) And with New York businessman Clifford Roberts, Jones built--and helped design--his "ideal golf course," the Augusta National Golf Club in Augusta, Georgia, which opened in 1933. In 1934, the club hosted its first Annual Invitational Tournament, which soon became the Masters. Jones participated in the event, including its famous green jacket award ceremony, through 1968.

By then he had long been wheelchair-bound by syringeomyelia, a rare spinal ailment that degenerates motor and sensory nerves and filled his later years with pain. Jones played his last full round of golf in 1948. Yet he bore his misfortune stoically and still enjoyed life. In 1958, he and his family traveled to St. Andrews in Scotland, where he was first dubbed "Bobby," and the town made him a freeman, the first American so honored since Benjamin Franklin in 1759. He loved the Old Course: "the most fascinating...I have ever played....There is always a way at St. Andrews, although it is not always the obvious way, and in trying to find it, there is more to be learned on this English course than in playing a hundred ordinary American golf courses." On December 18, 1971, play on the Old Course stopped and the flag was lowered to half-staff when word came of Jones's death. A year later, the town council named the Old Course's tenth hole the "Bobby Jones" hole in his honor.

Craig A. Lambert '69, Ph.D. '78, is deputy editor of this magazine.