State-of-the-art one-bedroom condominiums within walking distance of Harvard Square can go for more than $400,000 these days. Even faculty members have found it increasingly difficult to afford such prices. As one recently hired professor put it, "You can trace when someone joined the faculty by how far out they live." In an attempt to ameliorate that problem, and to address the need for more student housing, Harvard has been working on several fronts along the Charles River.

At One Western Avenue in Allston, where graduate-student housing will rise in 2003, construction of a 650-car underground garage (the base for the 240-unit housing complex) is well underway. Directly across the river in Cambridge, on a site now occupied by Mahoney's Garden Center, neighborhood opposition to Harvard's plans for a museum of modern art (see "Down by the Riverside: A Progress Report," May-June 2001, page 72) has led the University to propose a feasibility study for more much-needed housing. (A neighborhood committee has dismissed that alternative, too, and is pressing Harvard to donate the land for public open space, even as it looks for ways to downzone the area.)

|

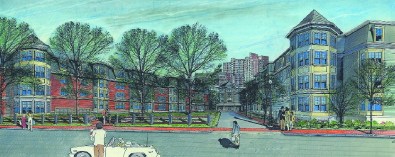

| Now under construction: a 120-unit residential development on Pleasant Street in Cambridgeport that will house faculty in traditional-looking condominiums. Harvard paid $40 million for the project, which will be built by a development partner. |

|

| Drawings courtesy Boyes-Watson Architects |

Harvard's December 4 acquisition of a 120-unit Cambridgeport housing development might therefore have come as welcome news to city officials, who have been pressuring the University and MIT to house more of their students and faculty. But when Harvard associate vice president for planning and real estate Kathy A. Spiegelman announced the purchase at a planning board meeting the same day, surprised local residents expressed shock and dismay that the new apartments would principally house Harvard faculty members, not Cambridge residents in general. The property had been owned by Polaroid Corporation (which filed for bankruptcy October 12) and its development partner, Spaulding & Slye Colliers; the partners originally planned to erect a 577-car garage, but after a suit by local activists concerned about traffic impacts, they instead proposed three residential buildings. Given the history of the site, Spiegelman said in an interview that she could "understand that the news of it being something other than what [neighbors] had expected was disquieting." She nevertheless defended faculty as legitimate members of the Cambridge community and expressed confidence that the project "is going to be a wonderful development and an amenity in the neighborhood."

The ownership model for the property will follow a pattern set at Observatory Commons, an earlier housing project built for the benefit of faculty members. By retaining ownership of the land beneath the housing (or achieving similar ends through shared-appreciation mortgages), the University will be able to offer about 102 units to professors at below-market rates of $300,000 to $350,000; the remaining 18 units will go into Cambridge's home-buyer program for affordable housing. The condominiums, with large bay windows, have been designed by Boyes-Watson Architects as one- and two-bedroom units in townhouse configurations, with "traditional-looking peaked roofs and entries," Spiegelman says, and come with underground parking.

Perhaps the most significant aspect of this housing project is that it marks the first time Harvard has used a development partner--Spaulding & Slye Colliers--for all of the construction. "One of the things that interested us about this," Spiegelman said, "is that if we are really going to change the percentage of folks that we house, we are going to have to produce a lot more housing than we have been--we don't have the capacity to do that internally, nor should we." Under Spiegelman's direction, Harvard Planning and Real Estate took great care in "developing standards, writing specifications, and going over drawings so that the end product will be what was paid for. It presents a different kind of challenge than building it yourself," Spiegelman acknowledged, "but if this works, it suggests that we might have the capacity to do more volume than we could if we had to do all the work ourselves."