Any new Harvard president was bound to establish new priorities, altering the expectations built up during the prior decade and forging new relationships with faculty members. Compared to the situation facing Neil L. Rudenstine in 1991--the University, in tight financial straits, was gearing up for a huge fundraising effort--the new millennium afforded opportunities to take stock of what use was being made of the wealth that had been accumulated in the prior decade.

Indeed, since assuming office last July, Lawrence H. Summers has articulated new goals such as enhanced undergraduate education (and restraints on grade inflation), faculty growth, and investments in science. Along with those broad institutional aims, he has begun to retune Harvard's academic culture. Summers emphasized "hard-won comprehension" over "soft understanding" in his October 12 installation address, for example, and has repeatedly stressed the primacy of teaching and scholarship over diverse outside engagements or programs not clearly rooted in the core faculties. Summarizing his remarks at a January 25 annual meeting of the Harvard Club of New York, he said in a subsequent interview, "There is no more important responsibility in academic leadership--whether by department chairmen, deans, or presidents--than setting high standards, insisting that high standards be met, and calling for excellence in serious scholarship and in commitment to teaching."

Those public pronouncements have been accompanied by private reviews of programs and by the active questioning of every aspect of University operations. Some of those questions have had a bearing on public policy, as in his thoughts on the academy's attitude toward military service and queries about Harvard's off-the-books financing of ROTC.

Such changes in priorities and personnel, accompanied by seemingly broad skepticism concerning Harvard's contemporary position, were likely to engender some friction. But who would have forecast a firestorm?

At the close of business on December 21, Harvard settled itself for a long winter's nap. The holiday lull was broken the next morning by a front-page Boston Globe story headlined, "Harvard 'Dream Team' roiled." Three members of the Afro-American studies department, it said, might decamp for Princeton. (Those named were chairman Henry Louis Gates Jr., DuBois professor of the humanities; Cornel West, Fletcher University Professor; and K. Anthony Appiah, Carswell professor of Afro-American studies and of philosophy.)

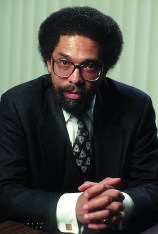

|

| Cornel West |

| Jon Chase / Harvard News Office |

Their reasons were reported, without attribution, as ranging from a meeting at which President Summers was said to have "rebuked" West for his scholarly performance, to the president's perceived reserve on affirmative action and his style generally. The subject was particularly heated, perhaps, because Rudenstine had ranked Afro-American studies at the top of his priorities, recruiting scholars and securing substantial resources for the department, and commenting extensively on diversity throughout his presidency. The article quoted Summers as regretting any "very unfortunate misunderstanding" of his views, and a subsequent University statement affirmed his interest in retaining all of the faculty members at Harvard.

The ensuing clatter became deafening. The news office handled queries from some five dozen media organizations. During a time of war and economic recession, the story made the New York Times seven times by January's end--twice on page one and once indexed there. At mid month, a Washington Post columnist counted nearly 300 newspaper and magazine articles on the subject. If few of these accounts added to the store of facts, they at least proved the appetite for stories about matters of race, Harvard and its new president, and his interaction with "star" professors.

The intersection of president and professor--Summers and West met in October--apparently had all the ingredients for a perfect storm. A popular teacher, West is also widely known outside the academy for general-interest publications like Race Matters, as a lecturer, for a recent CD recording called Sketches of My Culture, and as campaigner for past and prospective presidential candidates Bill Bradley and Al Sharpton. The details of their exchange (news accounts mentioned scholarly research, grading, and outside activities versus academic obligations) aren't known: Summers maintains the privacy of conversations with faculty members, and West, who underwent surgery for prostate cancer in late January, was unavailable for further comment. But West was quoted as saying that he had been "disrespected" and had nearly resigned on the spot.

Curiously, none of this became public until the Globe article some two months later--and then accompanied by the anonymous complaints about affirmative action and presidential style. By that point, Summers had spoken on diversity, noting in his installation address that compared to the Harvard of a century ago "where New England gentlemen taught other New England gentlemen," the modern institution is open to all and so offers "a better education to better students who make us a better university."

Amid meetings with Gates, West, and others following the first wave of news coverage, Summers released a statement January 2 (www.president.harvard.edu/speeches/2002/diversity.html) affirming his commitment to "create an ever more open and inclusive environment that draws on the widest possible range of talents"; citing Harvard's "approach to admissions" (to which the Supreme Court referred in the 1978 Bakke decision as allowing appropriate consideration of race and ethnicity); and declaring that he was proud of the Afro-American studies program "collectively and of each of its individual members."

The initial controversy blossomed into journalistic discussion of presidential style--an issue the Times headlined as "Harvard President Brings Elbows to the Table"--on matters ranging from a proposal for a Latino studies center (its proponents said they found the president initially dismissive) to the possibility of relocating the Law School to Allston.

Although much of the comment was again unattributed, the Times quoted Geyser University Professor William Julius Wilson (who teaches in the Kennedy School and Afro-American studies) as objecting to aspects of Summers's "behavior" as "quite shocking." Gates told the Globe that professors' egos are "fragile and insecure," so a president should always "manifest a sense of noblesse oblige in his dealings" with them. Other people who have had sustained contact with Summers on a variety of issues--notably Jeremy R. Knowles, dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, and Robert C. Clark, dean of the Law School--went on record as welcoming the president's interest in raising analytical questions.

Richard P. Chait, professor of higher education, did perhaps the clearest job of cutting through the semantics. In an essay in the Chronicle of Higher Education, Chait compared the president's forceful style to that of many faculty members in their confrontational questioning of students as a learning technique, and in their "brutally candid and cold-blooded" peer review of tenure candidates' qualifications. Recalling his own experience on the receiving end of a Summers query, Chait asked, "Should the president not be allowed to ask hard questions of the faculty...?" (He went on to "guess that Summers has only started to realize that the president of Harvard...has a built-in microphone that amplifies at least fivefold the volume of any question, comment, or criticism that he offers"--and to echo fellow Education School professor Howard E. Gardner's advice that Summers cultivate the art of "listening charismatically.")

There matters rested until January 25, when Anthony Appiah--soft spoken as ever throughout the Afro-American studies controversy--accepted an offer to move to Princeton. News accounts inevitably put the decision in the context of the larger story, but Appiah insisted otherwise, citing the attractions of his new position. He will be Rockefeller University Professor of philosophy and a member of Princeton's Center for Human Values; he will be affiliated with Amy Gutmann, now provost, formerly director of the center, and coauthor with Appiah of Color Conscious; and he will be much closer to his New York City residence, from which he has commuted for most of the time since he joined the Harvard faculty in 1991 with Gates. (Concluding its own courtship, Harvard countered Appiah's news on January 29, announcing that Michael C. Dawson, Ph.D. '86, past chairman of the University of Chicago's political science department, will return to Cambridge this summer as professor of government and of Afro-American studies. Dawson, author of Behind the Mule: Race and Class in African-American Politics and Black Visions: The Roots of Contemporary African-American Political Ideologies, directs Chicago's Center for the Study of Race, Politics, and Culture.)

Whether Gates, West, or others also decide to depart may not be known until this summer. Whatever their decisions, and for whatever reasons, they will now be made, for good or ill, in the glare of national publicity.