Our nervous system sends us thousands, if not millions, of buzzing sensations each day. Fortunately, the brain lets us screen important sensory messages from trivial body chatter. This filtering ability explains why most of us never seek medical attention for common aches and pains such as muscle twinges, dizzy spells, or headaches. But the same minor ailments prompt somatizers and hypochondriacstwo distinct but related groups who suffer from frazzled mind-body connectionsto see doctors at twice the average rate (accounting for up to one third of all primary-care calls) and to rack up an estimated $30 billion annually in unnecessary medical costs. Now associate professor of psychiatry Steven Locke may have found a way out of this costly black hole.

|

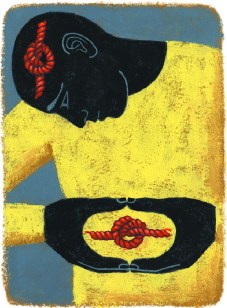

| Illustration by James Steinberg |

Locke counsels somatizerspatients who transform mental and emotional experiences, like job-related stress or miserable sex lives, into physical symptoms such as back pain, dizziness, headaches, and gastrointestinal discomfort. In a study presented at this year's meeting of the American Psychosomatic Society, he and colleagues from Harvard Vanguard Medical Associates found that a group of 114 somatizers and other "high utilizers" saved money on healthcare by enrolling in a nontraditional behavioral-therapy course. The six-week program taught participants to reframe their symptoms through self-awareness exercises, meditation, and cognitive homework; they studied mind-body relationships and learned how moods and behaviors could affect their health. In the year after therapy, participants' medical costs decreased, on average, $1,616 apiece. Even the control group of 176 patients (who were referred to the course but didn't enroll) saved their insurers an average of $608 each. Similar interventions might also help true hypochondriacs, who cultivate expensive delusions about nonexistent illnesses.

Locke's program participants had spent an average of $4,078 on inpatient costs, outpatient visits, and diagnostic services (excluding optometry, dentistry, and pharmacy costs) in the 12 months before treatment. In the 12-month post-treatment period, their medical expenses dropped to an average of $2,462. The control group's expenses also dipped respectably, from $4,347 to $3,739. (Locke speculates that the latter savings stem from transformations in thought: where participants learned anxiety-management skills, control-group patients may have benefited from doctor-patient conversations during referral.) Once Locke subtracted program-delivery costs from the savings, he found that the therapy had cut healthcare costs about 25 percent and returned about 150 percent on investment. Because patients weren't randomly assigned to the treatment, "potential for selection bias in group assignment is inherent," Locke writes. Still, the results impress.

Although leaping to real-world applications is tricky, Locke estimates, conservatively, that 10 percent of American adultsabout 20 million peopleare somatizers, hypochondriacs, or other high utilizers who could benefit from behavioral therapy. If just one percent, or 200,000 of these people, enrolled in therapy programs and saved just $500 each (about half the cost of a CAT scan), $100 million would melt off the nation's healthcare tab.

Cognitive behavior therapy, Locke asserts, can help patients reframe their symptoms and control their spending. And it could prove more effective over time than quick-fix treatmentslike psychiatric drugs or a doctor's verbal reassurancesthat glaze over anxiety but can't erase it. Could this therapy trump psychiatric drugs like Valium? Not so fast, says Locke. Cognitive behavior therapy is "cost effective, it's clinically effective, but it reaches only a small percentage of the people who could benefit from it." That's partly because the disorders it is designed to treat pose tough challenges in modern medical environments where doctor-patient relationships wither under tight schedules and anxious sufferers are herded toward expensive drugs. The other part of the problem lurks in how this country treats mind-body medicine.

"We don't train doctors to deal with it," says professor of psychiatry Arthur Barsky, director of psychiatric research at Brigham and Women's Hospital. "The doctor's job is to identify 'real' diseases and treat them. Everything else is chaff." Barsky works with hypochondriacs, those more extreme patients who persistently believe they're sick or constantly fear disease. For a female hypochondriac, worry about breast cancer can lead to obsessive rounds of self-administered breast exams; breasts then become tender, reinforcing the anxiety. "Once you really suspect you're sick, you pretty much select the information that confirms your worst fears," Barsky says. His research shows that hypochondriacs also benefit from behavioral therapy. But medical paradigms don't prepare doctors for symptoms that don't spring from organic disease or patients who suffer but aren't sick. "America's leading medical schools are focused on technological biomedicine," Locke explains. "The systematic exclusion of the mind-body relationship is a deficiency."