A Muslim performs ritual prayer, the salåt, five times a day, and pays attention to certain prescribed obligations while doing so. First, avoid contact with ritually unclean surfaces. A prayer rug solves that problem and can be rolled up and kept on one's shoulder; it is an object both quotidian and sacred. Second, a Muslim must pray facing toward Mecca. In a mosque, a mihrab, or niche, in the wall closest to Mecca, orients the worshippers. The design on a prayer rug is based on a niche motif, a directional indication that reminds the faithful of this second obligation.

A Muslim performs ritual prayer, the salåt, five times a day, and pays attention to certain prescribed obligations while doing so. First, avoid contact with ritually unclean surfaces. A prayer rug solves that problem and can be rolled up and kept on one's shoulder; it is an object both quotidian and sacred. Second, a Muslim must pray facing toward Mecca. In a mosque, a mihrab, or niche, in the wall closest to Mecca, orients the worshippers. The design on a prayer rug is based on a niche motif, a directional indication that reminds the faithful of this second obligation.

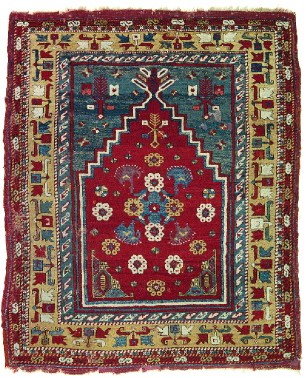

The rug above is Turkish, probably from the Bergama region of western Anatolia; was made of wool warps, wefts, and hand-tied knots in the nineteenth century; and is the sort of rug in vintage and character that until recent decades could routinely be seen serving as hard-traffic floor covering in Brahmin residences on Beacon Hill. This specimen was an anonymous gift to the Harvard University Art Museums just last year. Its preciousness is recognized in an exhibition of 15 Islamic prayer rugs, The Best Workmanship, the Finest Materials, on display at the Arthur M. Sackler Museum through December 15.

On the red ground within the niche motif of the rug are rounded, many-petaled blossoms, and the borders show the Ottoman tulip, a favorite motif. "There's a conception in the Islamic world of paradise as a verdant garden," says Amanda Phillips, the curatorial intern who organized the exhibition. "This perception of the afterlife as a garden, and its presence on prayer carpets, is a reminder that the best way to heaven is through prayer and supplication."

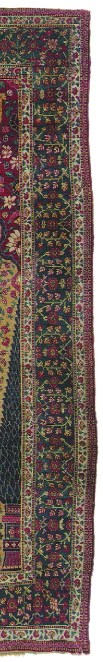

The tulips are angular and abstract because the rug is coarsely woven, although sturdy, and its relatively few knots per square inch favor angular over curvilinear designs. Compare the detail of an eighteenth-century, densely woven, so-called "mille-fleurs," Indian or Mughal piece, at left. The rugs in this exhibition come from geographic and cultural regions ranging from the plateau of Anatolia to Kashmir in the Himalayas and differ markedly in structure and design, but whether prayer rugs were made of sheep's wool and goat hair on a portable loom by a nomadic woman on the steppes of Central Asia, or of silk by a man in a city workshop in Tabriz, the weaver's aim, says Phillips, was to produce "a superlative surface upon which to affirm the Muslim faith."

Images courtesy of the Harvard University Art Museums