Emilie Norris and Nina Cohen are the prowlers, officially sanctioned and strictly aboveboard. They range widely throughout Harvard to conduct the University Cultural Properties Survey. Norris and Cohen are invited into administrative offices, residential Houses, final clubs, into attics and basements, to see what they can find that's worth keeping track of. On a mantel at Harvard Magazine's offices, Norris saw a stout wooden object, photographed it with her digital camera, and recorded its vital statistics to be entered into the database she is building. The 42-inch-long object has a plaque attached, inscribed as follows: "The Last Harvard Pump Handle/Rescued in 1905 by B. Meredith Langstaff '08/Now presented thru the N.Y. ass'n of his class to the Harvard Alumni Bulletin 26 April 67."

|

| Virgin and Child, egg tempera and gilding on wood, late seventeenth to early eighteenth century. When Norris was shown this Russian icon, it was residing in a file cabinet. |

| Photograph by Jim Harrison |

* A Persian carpet worth more than $100,000 in a House senior common room (it has since been moved to the masters' residence);

* Another Oriental rug, in an important central-administration office, that had had a hole cut through it to allow the passage of computer wires;

* A painting (twentieth-century) worth perhaps $1 million hanging in a regional studies center;

* A Daumier print in a frame with cracked glass, almost disappeared behind a radiator;

* A canister containing 80-year-old movie film, the only known footage of Pierre-Auguste Renoir at work, found in a broom closet behind the Drano;

* A plaque at the Medical School commemorating the last dog to die in the research that led to the development of insulin;

* A nondescript desk at the Kennedy School that formerly belonged to newsman Edward R. Murrow;

* A Harvard flag that went to the moon;

* President Josiah Quincy's walking stick, with cracks in its shaft said to be the result of vigorous whacks to the bottoms of unruly undergraduates.

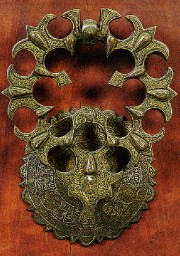

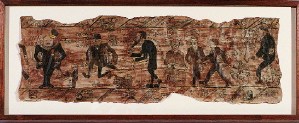

| Upper left: This knockable sixteenth-century Egyptian door knocker--of brass, engraved and inlaid with silver, copper, and black compound--enlivens an office wall. Middle left: Found in a little-used (dare we say dingy) basement storage room at Radcliffe was this oil on canvas, by an unknown American artist, of a woman with eyeglasses. Her hair style and dress supply an approximate date of 1830 to 1840, but her name is a mystery. There was no Radcliffe then. She appears scholarly. Perhaps a sister in an intellectual family? Norris and Cohen hope that a student or scholar will do some research and discover her identity. Below: Julius Klein (1886-1957) earned a Ph.D. in history at Harvard in 1915 and made this portrayal of departmental bigwigs, in ink with black and brown washes, in a style evocative of the Bayeux Tapestry, which chronicles the Norman conquest of England |

Above: Julius Klein (1886-1957) earned a Ph.D. in history at Harvard in 1915 and made this portrayal of departmental bigwigs, in ink with black and brown washes, in a style evocative of the Bayeux Tapestry, which chronicles the Norman conquest of England |

| Photographs by Jim Harrison |

Important goals of the survey are to see that certain of these objects are documented for insurance purposes and that all are being, or will be, cared for considerate-ly. Norris arrived at Peabody Terrace just in time to persuade a well-intentioned maintenance man not to touch up a damaged Ellsworth Kelly sculpture in the courtyard with a can of Rust-Oleum. To achieve her preservationist goal, Norris employs sweet reason, nothing totalitarian.

|

| Nina Cohen (left) and Emilie Norris, project director of the University Cultural Properties Survey, in a decorous Harvard drawing room. According to its label, the mid-eighteenth-century Dutch or Flemish apothecary jar before them, of tin-glazed earthenware with a brass top, is meant to contain Spanish fly. |

| Photograph by Jim Harrison |

She was for many years on the curatorial staff of Harvard's Busch-Reisinger Museum and had often heard stories of orphaned artworks here and there at Harvard. After a series of murals by abstract expressionist Mark Rothko, hanging in a function room at Holyoke Center, were discovered to have been wrecked by sunlight ("Damaged Goods," July-August 1988, page 25), Norris began to agitate for funding to undertake her survey. Many who heard her agreed that her proposal was worthy, but no departmental budget seemed to contain the money for it. Finally, then-provost Harvey Fineberg funded a three-year project. Norris and Cohen (formerly with a prominent local auctioneering firm) are now midway, temporally and geographically, in their trek through Harvard.

"It would have been nice if Harvard had started doing this 200 years ago," says Norris, who is greatly enjoying her pioneering work. (In fact, she has found an earlier, four-page, handwritten "Inventory of the Personal Property of Harvard University in the custody of the Librarian," made by Benjamin Peirce in 1828. It lists such possessions as two "coal kettles," busts of Sappho and of Sir Isaac Coffin, and "the old Chair used by the President on Commencement Day.")

Because the survey is ongoing, Norris invites leads and anecdotes from denizens of Harvard past and present. She may be reached in her Fogg Art Museum office by telephone at 617-384-7258 or by e-mail at norris@fas.harvard.edu.