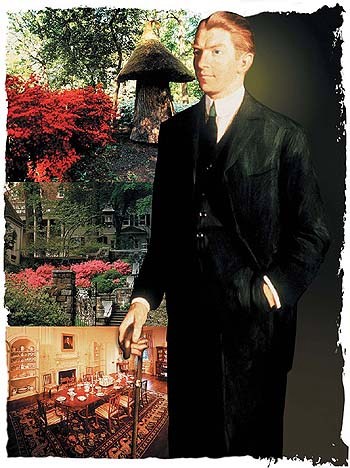

That "Museum" is the Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, a 983-acre estate in the Brandywine Valley. It had served as the family home to five generations before du Pont converted it into the world's preeminent showplace of furniture and decorative arts made or used in the United States before 1860. In an era when most Americans were enamored of European culture, art, and furniture, he recognized the intrinsic beauty of objects made by American hands. A passionate collector with virtually unlimited resources, he assembled the more than 89,000 antiques that fill the museum's 175 rooms and framed the mansion with magnificent plantings, including a Quarry Garden, a Sundial Garden, a Pinetum, and an "Enchanted Woods" for children.

"It takes a sack of money to collect the way Harry du Pont has done," a friend once remarked. "But it also takes a lot more than money. It takes a sure eye for beauty, a perfect sense of balance, and an incredible amount of hard work."

Du Pont was a born collector. A shy and lonely child who disappointed his autocratic fathera West Point graduate, Civil War hero, and United States senatorhe found refuge in collecting bird's eggs and stamps. He was a poor student. "I know that I am stupid," he told his father, "but I think that if I had a tutor to myself, I could pass my preliminaries." Yet after studying all summer with a tutor, he still placed last in his class of 16 at Groton.

His mother, who had already buried five children, coddled her only surviving son through childhood illnesses. They were devoted to each other, and her death weeks before his graduation from Harvard devastated him. His father immediately summoned him home to take charge of domestic responsibilities. Cousins who'd always taunted him for his shortcomings as an athlete and student now called him "milkmaid."

He had taken classes at the Arnold Arboretum, however, that launched him on a serious study of horticulture. His affection for flowers became a passion. He planted his first narcissus bulbs at Winterthur in 1902; their descendants still bloom each spring along March Walk. He called himself Winterthur's head gardener. Working with MIT-trained landscape architect Marian Coffin on nearly 70 acres of gardens and a model 2400-acre farm, he developed what is often considered America's finest country estate.

Besides renovating and enlarging the house, he constructed modern barns. When he expressed interest in breeding Holstein-Friesian dairy cattle, his father replied, "That's a splendid idea. It will cost less than maintaining a yacht, and it may result in some good for humanity." Over the years, du Pont informed classmates about his prize-winning animals: "A cow from this herd completed on June 16, 1942, the highest butterfat record ever made on two-time milking by any cow of any breed or any age in any country through all time," he wrote in their fortieth report. On tax returns, passports, and other legal documents, he often chose to identify himself as a "farmer."

A 1923 visit with his wife to the Vermont farmhouse of friends ignited his interest in Americana. "I had always thought of American furniture as just kitchen furniture," he recalled. "I didn't dream it had so much richness and variety." He soon purchased his first American piece, a 1737 Pennsylvania chest now in the Tappahannock Room at Winterthur. He also began saving the interiors of old houses that were about to be razed, eventually incorporating them into Winterthur as authentic settings for his antiques.

Collecting American decorative arts immersed him in a community of enthusiasts and experts whom he regularly consulted. His shyness evaporated when he spoke with people who shared his interests. Because he always acted as his own agent, not buying anything until he'd seen it for himself, he developed a connoisseurship and authority that others respected. He was approached to help save New York's Cooper Museum, which he did by convincing the Smithsonian to acquire it. And when Jacqueline Kennedy assembled her 12-member White House Restoration Committee, she chose him to serve as chair. Afterwards, she called on him to suggest the first White House curator.

The poor student had matured into an expert on cattle breeding, horticulture, and Americana. He had, in conjunction with the University of Delaware, developed a degree-granting program in American decorative arts. When Winterthur opened as a museum in 1951, du Pont joined the staff in dusting and polishing furniture before the Saturday Evening Post arrived to do a story that would feature its first-ever use of color photography. "I always knew what I wanted Winterthur to be, but I never thought it could happen until after I popped off," he told the interviewer. "Then one day I got to thinking, if I want a museum here I ought to see the job through myself. Besides, I suspected there would be some fun connected with it, and I wanted to be in on it."

|

| Photomontage by Bartek Malysa. Photographs courtesy of Winterthur. "Enchanted Woods" by Rich Dunoff. Du Pont house exterior by Linda Earhart. Du Pont dining room by Gavin Ashworth. Henry Francis du Pont, 1914, by Ellen Emmet Rand, courtesy of Winterthur Museum. |

Shirley Moskow is a freelance writer with a special interest in culture and travel.