I doubt that I was the first farm boy accepted to Harvard University, but when I arrived in Cambridge you certainly could have fooled me. Fresh off the tractor, with a farmer's tan and a head full of Republican idealism, I fancied myself quite the moral authority. My ideological heroes occupied a wide range of the political spectrum, one that included both Rush Limbaugh and Ronald Reagan. I was all for intellectual diversity, so long as I was always right, and the Right was never wrong. It was shocking to discover that Harvard in its infinite wisdom had admitted another 1,599 individuals who were afflicted with this same moral infallibility. During my first semester, I found no shortage of people willing to lock horns with me. I believed that argument was the highest form of poetry, and viewed moderation as merely a refuge for the unrighteous. I was in good company.

|

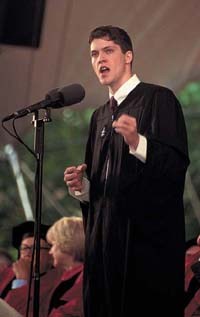

| Hart |

| Photograph by Jim Harrison |

College life, especially at an institution like Harvard, is remarkably adept at forcing people to pick sides. Whether the issue is war, politics, snow sculptures, discourse on college campuses is often reduced to a form of polemical dodge ball. Students hurl arguments at each other. After being nailed a few times, I started to rethink some of my previously intractable positions. Maybe conservatism doesn't have a monopoly on truth. Maybe homosexuality is not a choiceand if it is, maybe I don't get to make it for other people. Maybe I needed to rethink the way in which I treated the opinions of others. Myself a former member of the NRA, I had been wielding my opinions like a 10-year-old who had just found his dad's gun.

But opinions change. People change. Conformist pre-meds can become lifelong counter-culturalists just as readily as firebrand college activists can become Harvard professors. But as people, we are not merely the sum of our political opinions. Our personal value is not determined at the ballot box, nor are we justified in condemning one another simply because we attend different rallies. Elasticity of opinion is surely one of humanity's greatest virtues. But while our opinions may change, our value as human beings does not.

Too often at Harvard, this is forgotten. In our student publications and on our House open lists, we see Arab activists callously branded anti-Semitic terrorists, and organized Christians vilified as homophobic bigots. This accomplishes nothing. It seems rather our duty, both as educated members of society and as decent people, to respect our differences by maintaining civility in public discourse. It is possible to exchange even the most impassioned dialogue without resorting to pettiness. We are often told as children, "If you don't have anything nice to say, don't say anything at all." As we all know the attempt to silence a Harvard student is futile, perhaps we should strive to achieve the first condition of that precept. If we cannot conserve oxygen, we should at least preserve civility.

As we enter into what Harvard president Charles Eliot first called the "real world," our obligation to civility only increases. These last four years will shape a lifetime of actionsactions that will determine the environment in which our future unfolds. We are challenged to make that environment one that is driven by discourse, not denunciation, and one that is built on respect, not contempt.

Despite my own conversion to moderation, I still occasionally listen to Rush Limbaughalthough I no longer take notes. In one of his more thoughtful moments he said, "Being stuck is a position few of us like. We want something new, but we cannot let go of the oldold ideas, habits, beliefs, even thoughts." We can always find a bit of Veritas, even in the places we might not expect it. No one's opinions are immune to change. But it is how we express those opinions that makes all the difference. By honoring a code of civility and respect for the shared humanity of even those with whom we fundamentally disagree, we preserve the hope for understanding, and the possibility for change. Thank you.