In creating a diverse portfolio for Harvard's $17.5-billion endowment, the University's investment arm, Harvard Management Company (HMC), invests in hundreds of firms. That means weighing the probable return against the probable risk across scores of industries. Invariably, some of those investments will be questioned by members of the community or by the mediaas the University's investments in defense contractors led to questions of war profiteering during the recent conflict in Iraq. In April, 26 faculty members signed a petition decrying the University's investments in defense manufacturers after a Harvard Crimson article reported that, according to securities filings, HMC might earn more than $4 million from the boost the war gave defense stocks. Such discussions raise another way of balancing risks and returnsdoes the academy have a moral obligation to be socially responsible when it invests? "The University wants to be careful with its investment program," HMC president Jack Meyer, M.B.A. '69, says. "We have to be aware of social pressures."

As Brian C.W. Palmer '86, Ph.D. '00, sees it, the academy has an obligation to question where its investment dollars are going. "An investment firm is set up to be responsible to a limited group of stakeholdersusually just the investors who are in it for a maximum return over time," says the lecturer on the study of religion, who teaches a popular College course on globalization and human values. "Harvard is responsible to a much bigger group of stakeholdersits faculty, students, staff, and alumni." Indeed, Harvard has been debating its investing ethics for more than 30 years.

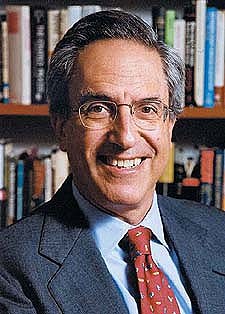

|

| Joseph L. Bower, chair of the Advisory Committee on Shareholder Responsibility |

| Photograph by Richard Chase |

The modern shareholder responsibility movement began in the spring of 1970 when the Project for Corporate Responsibility, backed by Ralph Nader, LL.B. '58, embarked on "Campaign GM." Owning exactly 12 shares of General Motors stock, the group successfully placed two proxy issues in front of GM that called for greater openness in the boardroom and a greater role for corporate social responsibility. Following extensive conversations with Harvard students, faculty, and alumni, the Corporation decided to vote against both resolutionsmuch to the disgust of many students and faculty.

Aware that the issue of the academy and corporate responsibility was just beginning, then-president Nathan M. Pusey appointed a committee on "University Relations with Corporate Enterprise." The reportby what came to be known as the Austin Committee after its chairman, Robert W. Austin, then Wilson professor of business administrationtraced the ethical obligations of the University as an investor and recommended that the president appoint an "officer of substantial standing" to serve as an internal ombudsman in regard to the University's investments. The report led the outgoing president to conclude in a May 1971 open letter to the community that Harvard should aim to play the "good citizen in the conduct of its business," and not to invest in companies that violated "fundamental and widely shared ethical principles."

President-elect Derek Bok appointed an assistant, Stephen B. Farber '63, to research the issues. In 1972, a shareholder proposal asked Gulf Oil to report on its ties to the Portuguese government then ruling Angola, charging that the company's presence in that African country lent support to a repressive and undemocratic regime. Harvard's 700,000 shares of Gulf stock quickly became a hot topic on campus. After Bok announced that the University would abstain from the vote, 25 student members of Afro and the Pan-African Liberation Committee occupied his office for a week in protest. In response, Bok dispatched Farber to Angola to gather first-hand information to help the University make future decisions.

In addition, to formalize a response structure capable of gathering information on dozens of similar proxy issues annually, the University in 1972 created the student-faculty Advisory Committee on Shareholder Responsibility (ACSR) to advise a new subcommittee of the Harvard Corporation, the Corporation Committee on Shareholder Responsibility (CCSR), on how Harvard should vote on proxy motions. That same year, Harvard also played the lead role in founding the Investor Responsibility Research Center (IRRC), a nonprofit think tank dedicated to gathering "high quality, impartial information on corporate governance and social responsibility issues"; Farber was named its director. Today, the Washington-based IRRC has more than 80 staffers conducting research for its 500 subscribers.

The IRRC and ACSR have played a leading role in determining how the University responds to issues as diverse as divestment from South Africa and strip mining. Last year, for instance, the ACSR reviewed 108 shareholder proposals raising such topics as genetically engineered food, nuclear power, secondhand smoke in restaurants, and the availability of drugs to treat HIV, malaria, and tuberculosis in Africa. It also deals frequently with corporate governance issues like diversity within boards of directors and executive compensation, including a proposal last year that fleetBoston consider freezing executive pay during periods of downsizing in order to help employee morale. (The ACSR split 4-5-2, and the CCSR opposed it in the end.) "Shareholders are one, and sometimes the only, way in which corporations are open to public scrutiny and, as such, shareholders can check corporate behavior that runs against the interests of consumers, workers, or society at large," says Emma S. MacKinnon '04, the undergraduate representative on the ACSR. Brian Palmer, who ran for the ACSR while an undergraduate and now studies the issue of corporate responsibility, says that the academy has a unique role in such debates. "Practices that might be taken for granted elsewhere in society, canand shouldcome up for debate here. That's one of the great strengths of the university world."

The 12-member ACSRfour elected students (three from the graduate schools), four faculty members nominated by the deans of the various schools, and four alumni nominated by the president of the Harvard Alumni Associationserve two-year terms and meet frequently during the March-to-June proxy season. Each member is assigned a handful of proposals to research and, after gathering information from the company, the proxy sponsors, and the IRRC, reports back to the committee. David professor of business administration Joseph L. Bower, who chairs the ACSR, says the group makes little effort to reach consensus. "We want as clear a set of arguments as possible," he explains. Previous committee precedent, he says, weighs heavily on the minds of committee members. The committee also looks carefully at the wording of proposals. "There's a limit to what you can achieve through the proxy system," Bower points out. "We can be very sympathetic to the issue and regard the proposal as preposterous." The committee, he stresses, tends to be more supportive of tightly worded questions that deal with concrete problems and issuesin other words, something within the purview of company management that could actually be accomplished after a shareholder vote.

The ACSR's recommendations, which are nonbinding, are passed on to the CCSR, which, in its most recent iteration, has been composed of two Corporation membersthe Senior Fellow (currently James R. Houghton '58, M.B.A. '62) and the treasurer (D. Ronald Daniel, M.B.A. '54). Traditionally, they follow the ACSR recommendation. Last year, for instance, of the 108 proxies decided, the ACSR and CCSR agreed fully 77 percent of the time. In other cases, the ACSR membership was split or one committee voted to abstain and the other recommended action of some kind.

The nuanced, case-by-case procedure used by the ACSR is critical, its backers say, because so many of the world's companies are too large and diversified to paint with a broad brush. The University tries to avoid blanket rules for its investments. The only prohibition that existsagainst tobacco holdingsfollowed a debate in the early 1990s. (There could be one more prohibition in the near future, though: an ACSR discussion last year about a proxy proposal for gun manufacturer Sturm Ruger and Company led the committee to recommend that the CCSR "seriously examine" whether the University should invest in gun manufacturers at all. According to University officials, that discussion has not yet occurred.)

Generally, Harvard and HMC try to avoid drastic actions. "Divestment is not something to be done lightly," Meyer says. "Both committees understand that [it] involves a certain cost and an uncertain benefit." Divesting, he explains, can have unintended consequences and potentially even harm those the action is meant to help. He points out that after apartheid ended in South Africa, for instance, archbishop and former Harvard Overseer Desmond Tutu, LL.D. '79, asked Harvard for help in encouraging companies to invest more money in that country's economy. Because Harvard by then had divested itself of all related stocks, it could not help. It is often better to stay invested and work to change the offending policies from within, Meyer says: "Companies would prefer you divest, rather than harass them with proxies as shareholders."

The ethical exercise and moral debates that occur within the ACSR's discussions are important for the University, those involved say. "The ACSR is one of the only places where people from all parts of the University can have a voice in how Harvard uses its immense financial power," Emma MacKinnon says. For his part, Meyer observes that even though no single issue currently dominates discussion, as tobacco and South African divestment once did, that's partly a result of the impact the shareholder responsibility movement has had on the market. "Companies," he says, "are much more attuned to these issues then they once were."

~Garrett M. Graff