Andrew H. Knoll, Ph.D. '77, Fisher professor of natural history, is a paleontologist who integrates geological and biological perspectives on early life. In his accessible new book, Life on a Young Planet: The First Three Billion Years of Evolution on Earth (Princeton University Press, $29.95), he puts readers in their place in this excerpt from chapter two, "The Tree of Life."

|

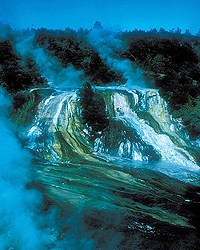

| Microbial ecosystem around a New Zealand hot spring suggests what life may have been like on early Earth. The long blue-green streamers consist of cyanobacteria. From the book. |

| Andrew H. Knoll |

Wandering through an alpine forest or snorkeling above a coral reef, we observe an ecology shaped by plants (or seaweeds) and animals, with large vertebrates at the top of the food chain and other creatures below. Ecosystems also contain many organisms that we can't see, but concern for their contributions is generally fleetingsurely bacteria and other microorganisms, tiny and simple, eke out their living in a world of our making?

As large animals, we can be forgiven for holding a worldview that celebrates ourselves, but, in truth, this outlook is dead wrong. We have evolved to fit into a bacterial world, and not the reverse. Why this should be is, in part, a question of history, but it is also an issue of diversity and ecosystem function. Animals may be evolution's icing, but bacteria are the cake.

Plants, animals, fungi, algae, and protozoa are eukaryotic organisms, genealogically linked by a pattern of cell organization in which genetic material occurs within a membrane-bounded structure called the nucleus. Bacteria and other prokaryotes are differenttheir cells lack nuclei. In terms of biological importance, eukaryotes would seem to have a decisive edge; eukaryotic organisms display a variety of form that ranges from scorpions, elephants, and toadstools to dandelions, kelps, and amoebas. In contrast, prokaryotes are mostly minute spheres, rods, or corkscrews. Some bacteria form simple filaments of cells joined end to end, but very few are able to build more complicated multicellular structures.

Size and shape surely favor eukaryotes, but morphology provides only one of several yardsticks for measuring ecological significance. Metabolismhow an organism obtains materials and energyis another, and by this criterion, it is the prokaryotes that dazzle with their diversity....

The metabolic pathways of prokaryotes sustain the chemical cycles that maintain Earth as a habitable planet.... [Moreover,] the cycles of carbon, nitrogen, sulfur, and other elements are linked together into a complex system that controls [Earth's] biological pulse. Because organisms need nitrogen for proteins and other molecules, there could be no carbon cycle without nitrogen fixation. Nitrogen metabolism itself depends on enzymes that contain iron; thus, without biologically available iron, there could be no nitrogen cycle...and, hence, no carbon cycle. Biology on another planet may or may not include organisms that are large or intelligent, but wherever it persists for long periods of time, life will feature complementary metabolisms that cycle biologically important elements through the biosphere.

By now it should be apparent why I insisted earlier that plants and animals evolved to fit into a prokaryotic world rather than the reverse. It is a prokaryotic world, and not only in the trivial sense that there are a lot of bacterial cells. Prokaryotic metabolisms form the fundamental ecological circuitry of life. Bacteria, not mammals, underpin the efficient and long-term functioning of the biosphere.