The day before I arrived in Kosovo, authorities in Pristina changed the name of the capital city's thoroughfare from Vladimir Lenin Street to Bill Clinton Boulevard. My ethnic Albanian cabbie pointed this out proudly as we made our way into town from the airport. Even if he had said nothing, I would have guessed something was up. The posters were a giveaway. Like giant, vertical billboards, they sheathed the concrete communist apartment complexes, adding familiar colors to the drab-by-design city architecture. One enormous Bill Clinton, then another, then another. Block after block, the larger-than-life image of America's forty-second president smiled down, amiably, paternalistically, one hand raised and cupped in a Miss America wave.

"Clinton is a great man," my English-speaking cabbie said, smiling. "America is a great country."

I stayed in Pristina for two days, training for the volunteer work I would be doing, reading UNMIK (United Nations Mission in Kosovo) publications, and learning land-mine safety. In the mornings there was time to roam the city. As I explored, the posters loomed high overhead, casting cheerful eyes down on the bustling city. I discovered smaller versions decorating the walls at the locksmith, bus station, and bakery.

Frankly, I got used to them. What surprised me more were my interactions with the Pristina locals. As I waited in line at the Internet café, a number of ethnic Albanian strangers offered me their computers. When I said that I was happy to wait, another man insisted on buying me a soft drink. Again I tried to decline, this time to no avail. A boy started a conversation with me. Within minutes he invited me to his house to have dinner. I told him I was sure his parents would not want a surprise guest. He said they would always be willing to host Americans, "our liberators."

Hearing this phrase—as I did countless times during my stay—always embarrassed me. What was my personal connection to their freedom, I wanted to ask. Sure, my country's politicians and military were critical in the process, but at the time I hardly knew Kosovo from Katmandu. So why invite me to dinner?

After training ended, my program director, Rand, drove me an hour outside Pristina to a smaller city named Gjilan (zhee-LAN), where I would live for the next three and a half months. The people in Gjilan, as in most towns in Kosovo, are almost all ethnic Albanians. There is, however, a small Roma (or Gypsy) ghetto.

Roma are marginalized throughout Europe, but in Kosovo their circumstance had a twist. Before NATO intervened in the war in 1999, the Roma opportunistically sided with the dominant Serbs. The strategy backfired: as authority was forcibly returned to the ethnic Albanian majority, the Roma were physically persecuted and in many cases forced to flee. The Gjilan Roma population, once as high as 4,000, dwindled to lows of a few hundred in February 2000, a year after the war. Today refugees are trickling back, although freedom of movement is still limited and most remain too frightened even to leave their street.

My work in Gjilan consisted primarily of helping returning Roma refugees register with the local government (to make them eligible for welfare and housing benefits) and, when there was spare time, teaching English classes. The evening we arrived, Rand led me around the neighborhood, introducing me to the people with whom I would be working.

It was a different kind of introduction from what I had experienced in Pristina. The Roma ghetto—essentially a muddy alleyway—seemed completely deserted. A stark floodlight, installed by the UN to discourage anti-Roma hate crime, gave the otherwise total darkness a weird, inhuman feel. A dead dog lay beside the road. Rand said this was a common sight. We pushed through a broken gate, navigated a narrow passageway, and stepped around the carcass of a burnt-out car that was filled to the dashboard with trash. We soon came upon a huddle of men, seated around a card table in the dark, dirty street. Seeing us, some of the men whooped cheerfully; others ignored us completely.

Rand immediately turned away to discuss something with one of the men in Serbian, leaving me to introduce myself. The first man I approached smiled, wryly, as I spoke, and shoved his large hand up to my lips, squeezing something in his fingers. "Eat."

I looked to Rand for reassurance, but failed to get his attention.

"Eat," said the man, again. "Fish."

The fish was squishy and cool and had lots of bones in it. I tried to use my tongue to sort out the bones from the meat. The man smiled and thrust a plastic cup at me. "Drink."

I was beyond the point of asking questions, and I drank the powerful raki in one swig, washing down the fish, bones and all. I coughed. The card players, almost all of whom were now watching me, exploded in laughter.

Another man came up to me. "You America?"

"Yes."

"I am O--. I am O-- bin Laden. I am killing America."

The wild laughter continued.

Americawas not high on my mind as I considered spending a year abroad. Notions of exotic, otherworldly adventures dominated my daydreams. Harvard, Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S.A.—it all felt limited, perhaps even old hat, with respect to WORLD. I wanted more.

I wanted more physically, but also culturally, spiritually, and linguistically. I wanted to plop myself in the middle of a completely foreign environment and sponge it up. Accomplishing this was harder than I ever imagined. As I traveled in Western Europe, the Balkans, and the Middle East, all anyone wanted to talk about was the United States. As curious as I was about their culture, they were more curious about mine. I became a lightning rod for questions.

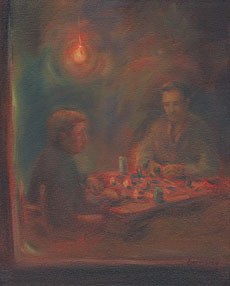

|

| Illustration by Lynne Foy |

Some of the questions were innocent enough. Teenaged Roma boys, for instance, are keenly interested in the intimate lives of American college girls. "You know in American Pie, when...," they would begin, shyly. "Does that really happen?"

Other questions were more discomforting. One ethnic Albanian family, the guardians of an epileptic niece whose mother was killed in the war, always asked about medications. "When you go back to America, you will send us a cure, yes?" they would ask with unabashed hope. "They have a cure for everything in America."

Others simply left me at a loss for words. Traveling in the Middle East in December and January, I wound up spending Christmas in a run-down pension in Istanbul. As the owner and I watched BBC World News over breakfast, the anchor mentioned the American-Turkish diplomatic split. "This, I don't understand," said the old man, grimacing. "We have always been friends with you Americans. We have always welcomed you in our country. We just disagree about one thing. So why all this?"

I was speechless. Any thoughts I had on the matter—thoughts I would have promoted unreservedly in, say, a Cambridge conference course—now seemed pathetically insufficient. In this real-world context, an uninformed point meant more than looking silly in front of a teaching fellow. Here I was being asked to speak for my country. Hazarding an uninformed argument felt inappropriate—indeed inexcusable.

"I don't know," I said.

As time passed, this phrase increasingly worked its way into my vocabulary. Where I had been brazen in my political beliefs, I now found myself constantly second-guessing. It happened again in France when I was asked why American families were refusing to host French exchange students: "We may not agree about everything, but we still want to see your country, to meet Americans, to learn English. Why punish high-school students just because you don't like our president?"

"I don't know."

And it happened again in Bulgaria, on a bus, talking with a vacationing Serbian soldier. He asked me how America could cry bloody foul when Serbs killed ethnic Albanians and then turn an icy shoulder when ethnic Albanians killed Serb villagers in equally cold blood.

"I don't know."

And it happened once more in Jordan when I was asked what I thought of the "probable" link between the United States government and the September 11 attacks. The question stung me as absurd, but retaliatory words caught in my throat.

"I don't know."

Of all the questionsand all the question-askers, it was O--—O-- "bin Laden"—who posed one of the most poignant. We were sitting in his house—a one-room concrete cubbyhole opening onto a muddy corridor off the main alley in the Roma ghetto—playing chess. O-- is a chess addict. In fact, after introducing himself to me as "bin Laden," the next words out of his mouth were: "You play chess?"

"Sure," I said.

And so then and there, as unlikely as it might have seemed the moment before, I was invited to the house of this would-be terrorist for a Turkish coffee and a game. It was to become a ritual. Every week, I knocked on his door, equipped with several cans of Skopsko (a Macedonian beer popular in the Balkans) and we played chess late into the night. Sometimes O--'s wife cooked for us: chicken or sausage with red peppers, usually marinated in beer.

As we played, we sat on the folded single mattress O--'s wife shared with their two toddlers. As the man of the house, O-- slept on the floor. The room was sparsely furnished: a wood stove in the corner, a picture of Mecca on one wall, a poster of the Teletubbies on another, a small, antique-looking television on a stool.

As the games pressed on and the beer cans piled up beside the mattress, O-- occasionally revealed glimpses of his murky personal history. His father, I learned, was a Bosnian Serb. His mother was a Gypsy. He grew up in Sarajevo and was attending law school there when the Bosnian war broke out. O-- fought for the Serbs in both wars (Bosnia, Kosovo) and was twice defeated by American-led NATO forces. He spoke sparingly of his time as a soldier, and I never asked. Whenever he did mention those times, he would always finish by saying: "But war. Okay. I don't mind that."

I found this hard to believe. Given his lingering animosity towards America—which he knew only in the context of his war experience—I figured this was just a way of changing the subject.

It did become clear, though, that whether or not he "minded" the war itself, he was more upset by what happened in its aftermath. Confined to the Gjilan ghetto—physically, financially, and emotionally—the march of O--'s life had been reduced to an undignified crawl, amid dead dogs and litter, under the glare of UN floodlights. Dreams of finishing law school and becoming a judge had faded into realities of unemployment and uncertainty.

I don't know if any of this was going through O--'s mind when he asked the question, but clearly he was in a reflective mood. "America will fight Iraq," he said. "America will forget Kosovo?"

At first I thought it was a joke. "Why, O--," I said, "are you coming to like us after all?"

"No. I hate America. I am killing America," he said. But turning to look at his two-year-old son playing in the corner, he added, softly: "But I want that Sinbad is speaking good English. I want that he will be a judge, you know."

We were both silent for a moment, and then he repeated the question: "America will forget about Kosovo, will it?"

I thought about it, and answered truthfully. "O--, I don't know."

America was not high on my mind as I considered taking time abroad. Now, sitting in a Paris loft, reflecting on my travels and preparing for my return to Harvard, I can't seem to think of anyplace else. I don't feel bad about all the unanswered questions. It would have been worse to pretend to have answers I didn't. Nonetheless, the questions—and the people and the experiences behind them—haunt me in their sincerity and relevance.

I certainly plan to go abroad again, but right now I am looking forward to coming home. WORLD, U.S.A., Massachusetts, Cambridge, Harvard. There is a lot to be learned at home, and every reason to take this learning very seriously. After all, when I do go back abroad, I know there will be questions waiting for me.