|

| Photograph courtesy of Harvard University Art Museums © President and Fellows of Harvard College |

Just as a pair of Mandarin ducks, a symbol of conjugal contentment, nestle on the waterside, Genji and his greatest love, Murasaki, cozy up on their verandah while maidservants make a snowman in the garden. The blissful moment is shown in this illustration to chapter 20, "The Bluebell," of The Tale of Genji, perhaps the world's first novel and a masterpiece, by a Japanese noblewoman known as Murasaki Shikibu. Writing in the early years of the eleventh century, she spun a long tale, running to more than 1,000 pages in translation, with hundreds of imagined characters but starring Hikaru Genji, the Shining Prince, an ideal aristocrat. This was a time, according to Anne Rose Kitagawa, assistant curator of Japanese art at the Arthur M. Sackler Museum, "when Japanese aristocrats devoted themselves obsessively and almost exclusively to various aesthetic pursuits, including poetry, calligraphy, painting, music, the blending of incense, and all matters of taste." And to love, as Genji demonstrates repeatedly.

Japan was ruled by the aristocrats of the imperial court in Genji's day, but the military took over and by the thirteenth century courtiers had little to do but look after the nation's literary and cultural patrimony, at the center of which sat this canonical tale. "Japanese warriors often sought to legitimize their power by taking on various trappings of courtly culture," Kitagawa explained in a November 2001 Apollo article. "For this reason, depictions of The Tale of Genji became an especially potent form of cultural currency, for any warrior who could claim familiarity with it was one step closer to rationalizing his political authority."

|

| Photograph courtesy of Harvard University Art Museums © President and Fellows of Harvard College |

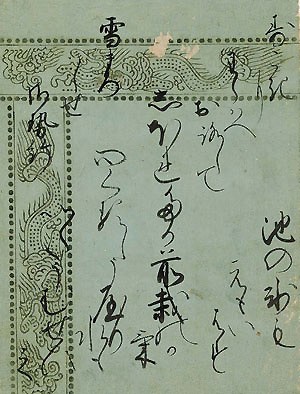

Harvard's Tale of Genji Album is such a depiction. It is a set of 54 pairs of leaves one ink-color-and-gold painting on paper and one textual excerpt, each about 9 1/2 by 7 inchesa pair for each of the novel's chapters. The paintings, done in 1509, are by Tosa Mitsunobu. The calligraphy is by six artiststhe example at left, also for chapter 20, by Konoe Hisamichi.

When the album came to the museum in 1971as a loan from collector Philip Hofer '21, L.H.D. '67it was thought to be much less old. Since then scholars have scrutinized and scrutinized and now consider it the earliest extant, complete, painted album-leaf-format version of the seminal tale and a treasure indeed. Kitagawa is at work on a book-length monograph about the album, detailing the history and multiple states of what she calls "this complex and magnificent work." Visitors to the exhibition A Compelling Legacy: Masterworks of East Asian Painting, at the museum through March 20, will find Genji and his darling in the moonlight, with their snowman-in-the-making and the ducks, contented still.