Nowadays it’s common for people to e-mail pictures to friends and family, but few of these photographers are as well-traveled as Steve Potter ’69, and even fewer have his skill with a shutter. Potter, communications director for iRacing.com, a developer of digital simulations for the motor-sport industry, has had a long career in that field. As the New York Times correspondent on car racing from 1979 to 1988, and later, as a marketing and communications manager for Mazda and Mercedes-Benz, Potter globetrotted to auto races and other sporting events. He has also refined his camera technique through decades of work as both a professional (Car & Driver) and high-level amateur photographer, so the images he sends out every few weeks to 500-odd friends and acquaintances often resemble those one might encounter in a gallery.

Steve Potter

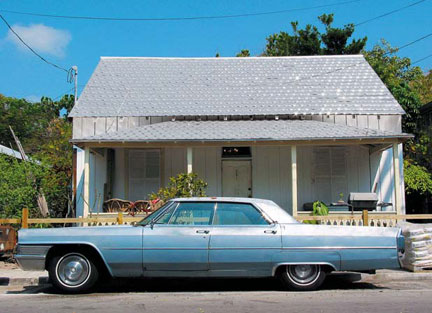

Cadillac and Metal Roof, Key West, 2003

Only about 20 percent of those shots are automotive in nature: hes as likely to shoot a gang of young Japanese toughs or a herd of horses in the Argentine countryside as a checkered flag. Once he even had a National Geographic assignment, to photograph a tribe in Panama. And sometimes he creates his own stories. In 2002, he and his wife, Kathy Drake, drove a 37-horsepower 1957 Morris Minor convertible from Charlotte, North Carolina, up the Blue Ridge Parkway to their home in Freehold, New Jersey; he recounted the trip for the Times in a piece he had earlier blogged as a “Minor Adventure.”

Steve Potter

Fish Taco Stand, Sayulita, Mexico, 2001

An early adopter of new technologies (The only advantage of early digital photography was that you could transmit images, he says), Potter has been image-blogging since 1998, when his list had only 25 recipients. He first learned the photographers art at the Harvard Crimson, where he absorbed a valuable lesson about the relationship between creator and audience: even though one’s black-and-white prints might look spectacular, there would be a vast loss of detail in the image as published in the newspaper. “It was crude, crude printing,” Potter recalls. “I learned that you always have to think about how the ultimate viewer is going to see the image. Nowadays I have the same issue, but with technology that is light-years away.”

Steve Potter

Watermelons,Sayulita, Mexico, 2001

In the digital era, People see the pictures on their computer screens, which are very low-resolution, he explains. The images I send are relatively small, and scan at only 72 dots per inch, like a TV picture. [Color photographs taken for magazines typically scan at 300 dots per inch or more.] And monitors have a luminescent backgroundits like holding a transparency up to a light source, giving a brilliance you cant get in a print.

Aside from the on-line distribution, Potter has typically published his photographs in books and periodicals, rather than mat and frame prints for gallery shows, even though many of his digital images can yield 20-by-30-inch art prints. But last year, Trinity Episcopal Church in Lakeville, Connecticut—located across from Lime Rock Park, a racetrack where Potter once worked—invited him to display some photographs in its annual art show. The church sold several pictures, and Potter will hang a few more on its walls at this year’s Labor Day weekend show.

Meanwhile, he nearly always has his Nikon D50 with him and continues to shoot prolifically. “I see pictures all the time, but it’s not always possible to stop and take them,” he says. “I’m like a fisherman, thinking about the ones that got away.”

Steve Potter

Cycle and Burgerville, Vancouver, Washington, 2004

~C.L.